by Michael Z. Muhammad, J.A. Salaam and Brian E. Muhammad

In 1995, the year of the Million Man March, the Black family, in particular, and the Black community, in general, were in trouble. The result of years of neglect, chemical warfare perpetrated against Black people in the form of crack cocaine, and the mass incarceration of Black men followed under the guise of the war on drugs.

Between 1984 and 1989, the homicide rate for Black males aged 14 to 17 more than doubled, and the homicide rate for Black males aged 18 to 24 increased nearly as much. During this period, the Black community also experienced a 20 percent to 100 percent increase in fetal death rates, low birth-weight babies, weapons arrests, and the number of children in foster care, according to statistical reports.

One in every four Black males aged 20 to 29 was either incarcerated or on probation or parole by 1989, contributing to the United States having the highest incarceration rate in the world. By 1995, that statistic had increased to nearly one in three.

Further exacerbating the trauma worldwide, the Black male was denigrated through negative racial stereotypes in American media and popular culture. There were negative images of Black men as savage, uncivilized, berserk beasts and Hollywood movies such as “Boyz in the Hood” and “Menace II Society” mass-marketed and spread the images worldwide.

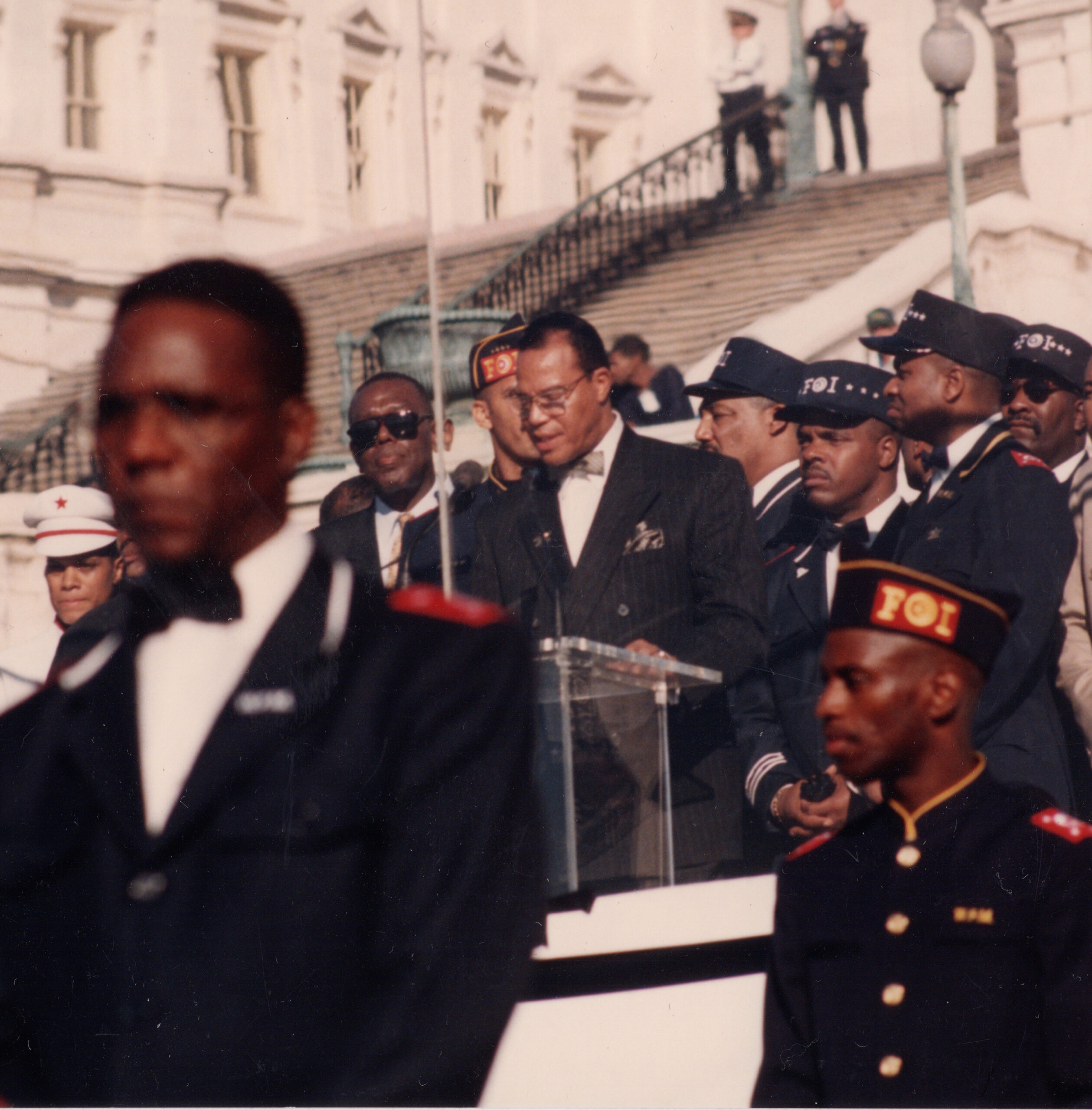

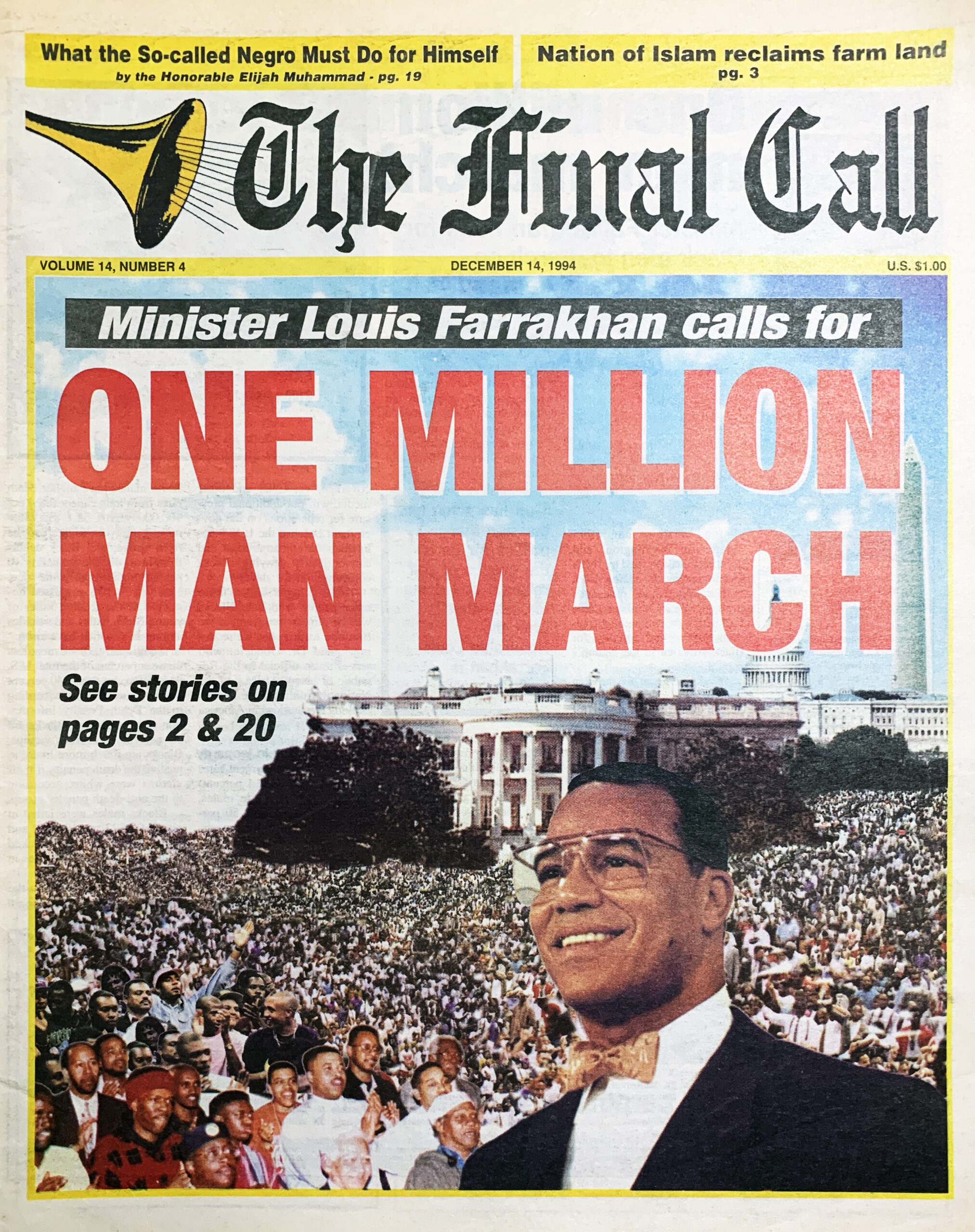

In response to this distress, Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam issued a call for a million Black men to come to Washington, D.C. This would not be another march for jobs and justice, it would be a spiritual activity tied to greater productivity among Black people regardless of what government did or did not do. The theme was atonement, reconciliation and responsibility.

The organizing effort around the idea of uniting and calling Black men to action caught like wildfire, spreading from mosques to churches to Black businesses to union halls to masonic temples to college campuses to the streets of Black America and beyond.

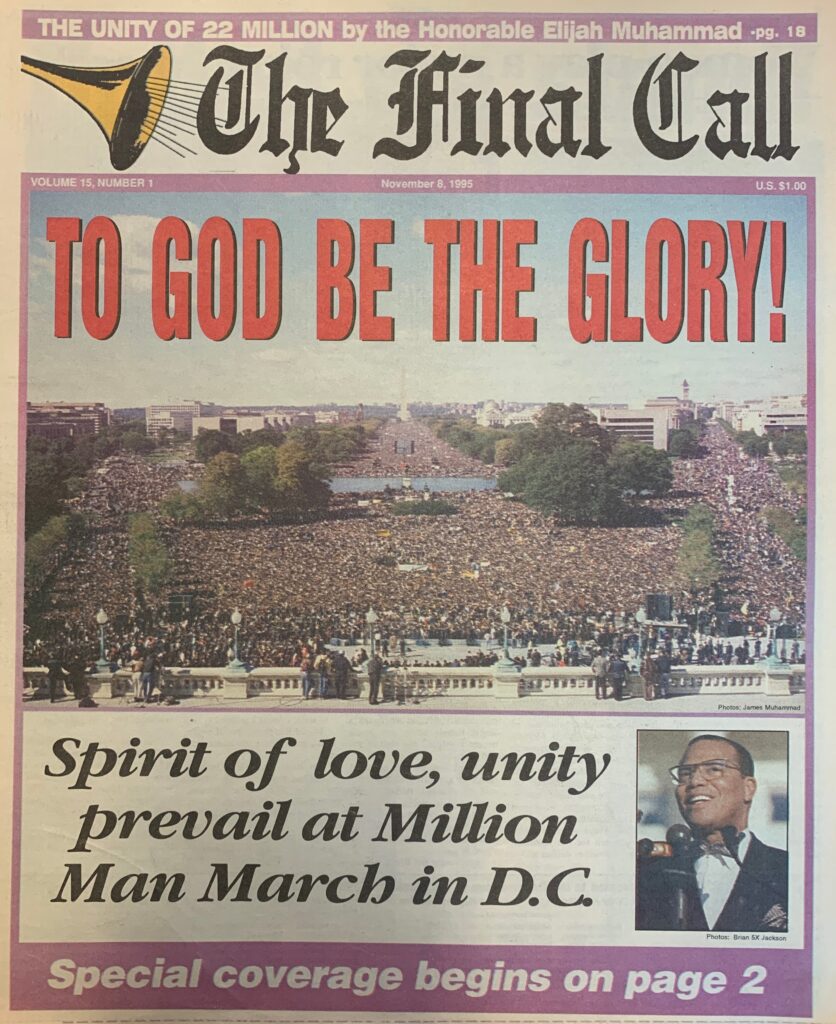

“The Million Man March was a phenomenal, marvelous demonstration of love and unity,” said Student Minister Ishmael Muhammad, the national assistant to Minister Farrakhan based in Chicago.

“A day unprecedented and unparalleled in human history,” he added.

“Never has there been an occasion where one man called a million of his brothers and nearly a million more responded. They answered not for protest or a rally to petition a government for a redress of grievances.

They weren’t assembled to take up arms against an enemy or to conquer. The million men were called to atone, reconcile, and accept the responsibility that is on our shoulders for the change that we desire in our lives, and we want in our communities as a people,” said Student Minister Ishmael Muhammad.

“The message of atonement, reconciliation, and responsibility is what I see has not been lifted up enough in these now 26-years,” he continued. “But the message of that day is what we really need to go back to.”

“On that day the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan was guided and directed by Allah to deliver a message for us, but the whole world on the principle of Atonement.”

The message laid out an eight-step process by which wrongs can be corrected, differences can be reconciled, conflicts resolved and peace secured.

“A generation or so has passed in these 26 years and it is our failure in not carrying that message to a new generation, or to continue the momentum that the Million Man March produced, that has us, you can say, back to where we were prior to the Million Man March,” reflected Ishmael Muhammad.

Although there were Million Man March wins such as increased Black adoptions, more men getting involved with community life and starting organizations to make communities safe and decent places to live, the central theme of atonement, reconciliation, and responsibility must be engaged more to address many of the current problems today.

“In these 30 years, the enemy has been working among us internally and externally to break us apart and keep us regulated to the circumstances and conditions he has created for us,” observed Ishmael Muhammad. “There will never be peace … until the peacebreaker is removed from among us,” he added.

The impact of the March

Since the Million Man March, there were subsequent Nation of Islam gatherings with atonement, reconciliation, and responsibility as the underpinning message. Gatherings like the “Million Family March,” the “Millions More Movement” and “10-10-15” or “Justice or Else!” convened over the last 26 years.

From the 2015 gathering, Abdul Sharieff Muhammad, the student Southern Regional Minister for the Nation of Islam based in Atlanta, established the 10,000 Fearless of the South. The initiative was birthed from Minister Farrakhan calling for 10,000 fearless to stand in the gap between Blacks in conflict and make “our community a safe and decent place to live.”

Abdul Sharrieff Muhammad said the “atmosphere is right to separate” and “do for self.”

“We should be doing what the Minister (Farrakhan) told us to do … July 4, The Criterion … going to the land,” he said. “Allah is moving us toward separation, and we should be getting ready and preparing for that.” He pointed to food shortages striking America and the adverse effects of tornadoes, hurricanes, and drought.

The Million Man March spawned innumerable gatherings, like the Million Woman’s March, the Millions Youth March, the Million Mom March, the Million Marijuana March and other “Million”-themed gatherings worldwide in Africa and the Middle East.

Held on a Monday, rather than a weekend, the March created a need for commitment by taking off work, school and paying your way to D.C.

Unlike traditional marches, Blacks organized and paid for the Million Man March. There was no corporate sponsor support that usually comes with strings attached, influencing what can be said or who can participate. Speakers that day were free to say what they wanted.

Abdul Arif Muhammad, general counsel for the Nation of Islam, said differences are to be expected with such a diverse representation of Black thought, both present and absent from the table. Some came as late as the day of the gathering.

“The March was really an effort through the work of the Minister and other groups and organizations,” said Student Min. Arif Muhammad. “But everybody that came to the table had their particular interests or point of view about what it meant,” he said.

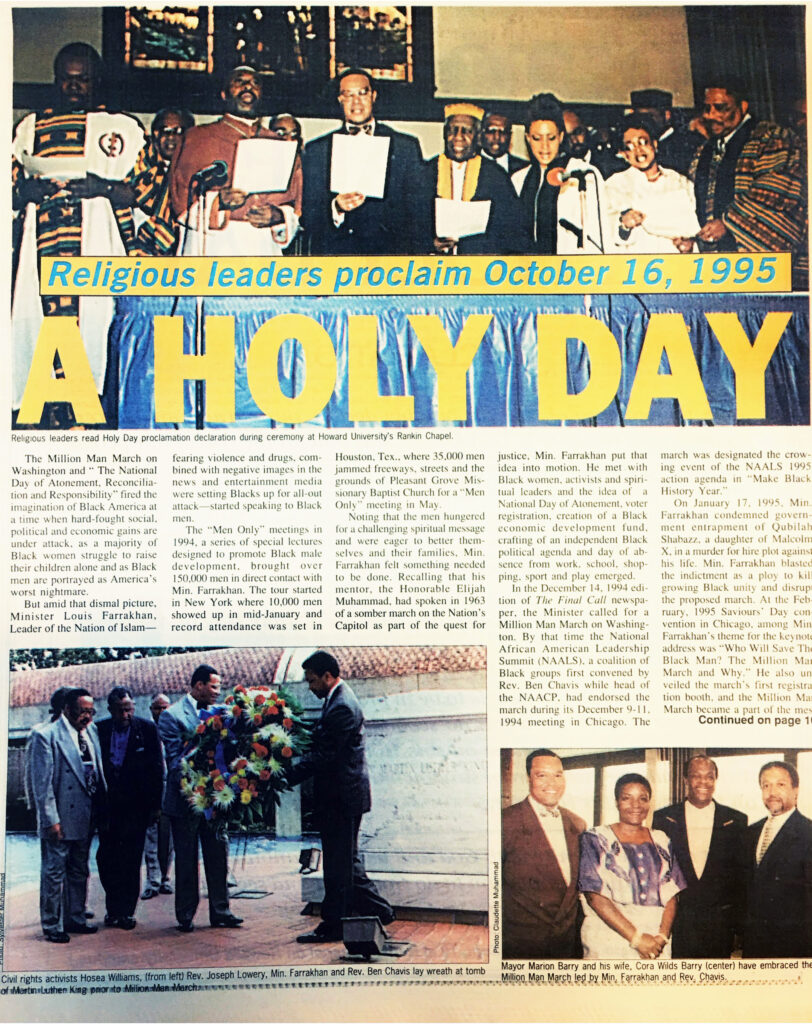

The day was declared a holy day and has been celebrated every year as the Holy Day of Atonement ever since.

Previous marches such as the 1963 “March on Washington” and subsequent gatherings were predominantly led by Christian pastors who primarily sought “jobs and justice” from the government, which has never been achieved.

Minister Farrakhan, in interviews, said although the Nation of Islam was not known for mass marches, the seed for a march was planted by his teacher, Elijah Muhammad, as they discussed the 1963 march. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad was critical of the spirit of frivolity and fun at the event and lack of the serious demeanor warranted for a march for jobs and justice.

He told Minister Farrakhan, “One day I’m going to lead a march, brother,” and “we won’t leave Washington until we get what we go for and that is justice.” Minister Farrakhan has said the comments were embedded in him.

But the Million Man March in Washington, D.C., wasn’t a walk in the park. Downtown businesses were shuttered, Congress shutdown, President Clinton, who left town the day of the March, joined others in trying to “separate the message from the messenger,” and force rejection of Min. Farrakhan. Neither the NAACP, nor the National Urban League endorsed the March. Some civil rights groups came on board shortly before the March, though their members and local chapters had already joined the effort. Police departments and National Guard units were at the ready if anything negative happened.

Nothing did. But attacks against the March never stopped. First, came the lie that Minister Farrakhan was a hater. After the March, naysayers tried to find fault with the most significant mass demonstration in the nation’s capital, and then came the effort to erase the event out of history. Now Oct. 16 comes and goes with little mention or skewed mention in mainstream media.

But that is to be expected.

Maulud Sadiq wrote a piece titled “The Million Man March Has Been Wiped From the History Books. Why?”

“Who benefits from Black people not building businesses, homes, hospitals, factories and entering into international trade? Who benefits from Black on Black crime and the separation of Black men and women? Who benefits when Black people don’t support their own?” he asked.

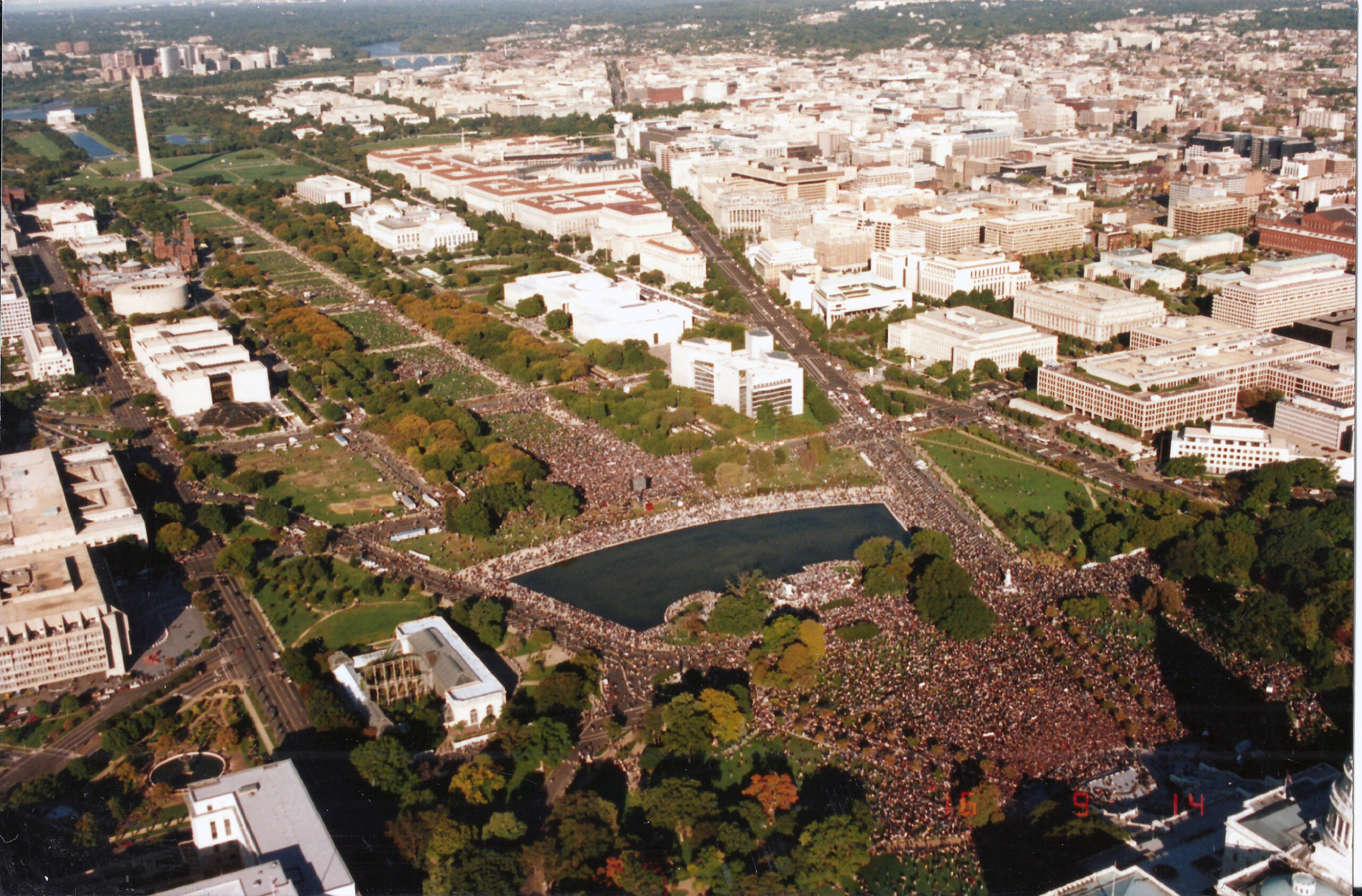

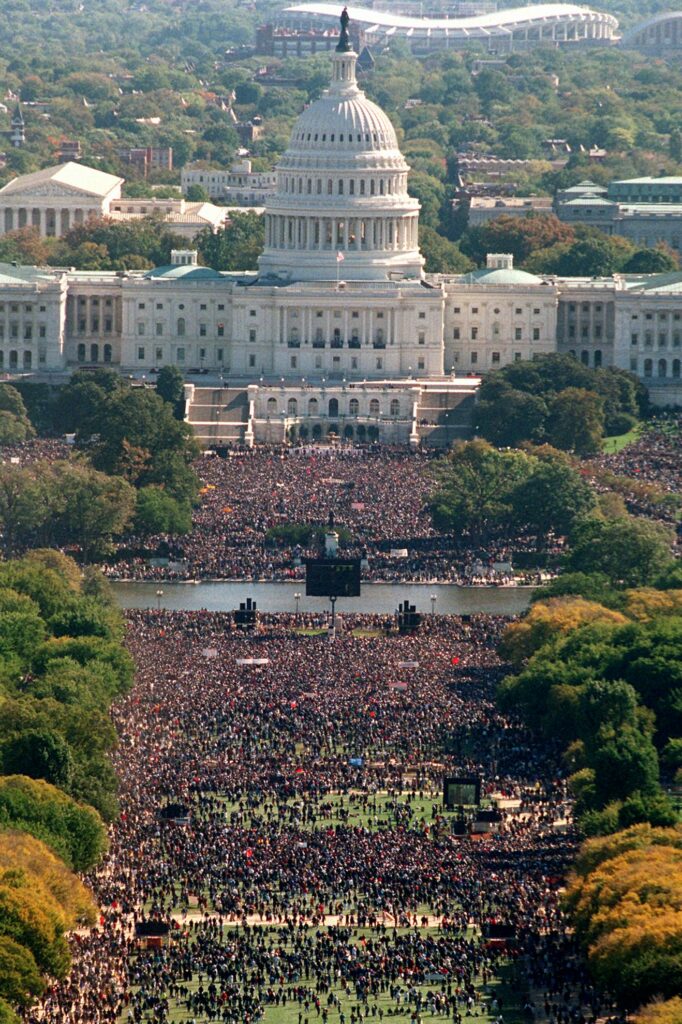

The Million Man March is among the largest gatherings of its kind in American history. Rather than rail against the government for all of its evils perpetrated against Black people, the March called for Black men to uplift themselves, their families, and their communities. And the call resonates today as the community continues to be beset by fratricide and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Soon after the very successful Million Man March, which saw a tremendous rise in voter registration, Black adoption and declines in violence and an explosion of community activism, came renewed attacks. Black pastors and churches were courted by Whites and told to shun Min. Farrakhan, who was roundly attacked in mainstream media, by politicians and acceptable Negroes who at the wishes of their White benefactors, often met with the Minister by night and repeated the slurs of the enemy during the day.

March lessons for today

But for many activists, the mantra of the Million Man March is needed more now than ever before. The message of Minister Farrakhan is required now more than ever before, they said.

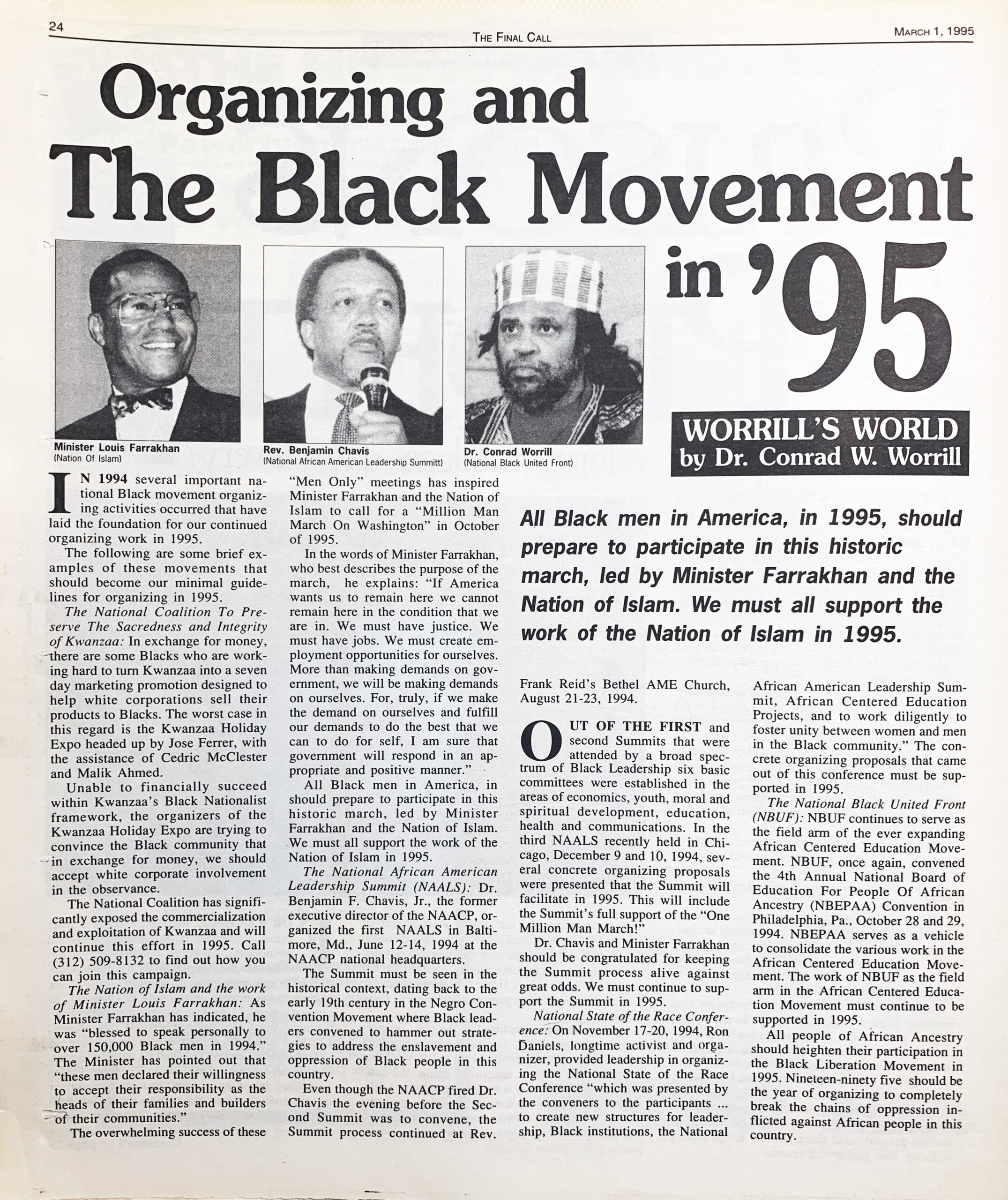

The late great Dr. Conrad Worrill, who supported and worked hard for the March as leader of the National Black United Front, once said, “The Million Man March was one of the most historic organizing and mobilizing events in the history of Black people in the United States.”

“So today, whether you like it or not, God brought the idea through me,” said Minister Farrakhan in his October 16, 1995 message. “He didn’t bring it through me because my heart was dark with hatred and anti-Semitism, He didn’t bring it through me because my heart was dark, and I’m filled with hatred for White people and for the human family of the planet. If my heart were that dark, how is the message so bright, the message so clear, the response so magnificent.”

“We must accept the responsibility that God has put upon us, not only to be good husbands and fathers and builders of our community, but God is now calling upon the despised, and the rejected to become the cornerstone and the builders of a new world,” he said.

“And so we are gathered here today not to bash somebody else. We’re not gathered here to say all of the evils of this nation. But we are gathered here to collect ourselves for a responsibility that God is placing on our shoulders to move this nation toward a more perfect union.”

In the 26 years since the March, America has not moved toward a “more perfect union,” it has been turned on its head. There was the election of a Black president. Diversity was the word of the day, profound structural change was called for in education and policing, but political factionalism has grown more intense.

White America clapped back with the rise and election of President Donald Trump, who remains a potent, divisive force on the political scene. America is falling apart as Minister Farrakhan forecast during his historic 2020 Saviours’ Day address, “The Unraveling of a Great Nation.”

Yet, the model for Black progress remains in the aims and purpose of the Million Man March, argued Student Minister Rodney Muhammad, who heads the Nation of Islam Muhammad Mosque No. 12 in Philadelphia and leads the Delaware Valley Region.

“Coming out of the March, we saw very tangible domestic results. Maybe two million younger Black people registering to vote. It sparked a tremendous interest in Black adoptions, the sharp increase in the membership of Black organizations and churches, but what is rarely discussed is the international ramifications. The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan’s follow-up was so colossal that it escaped many in America, the kind of global impact the Million Man March had. It began to link us with our people in other nations,” he commented.

Philadelphia brought a huge contingent of men to the 1995 March.

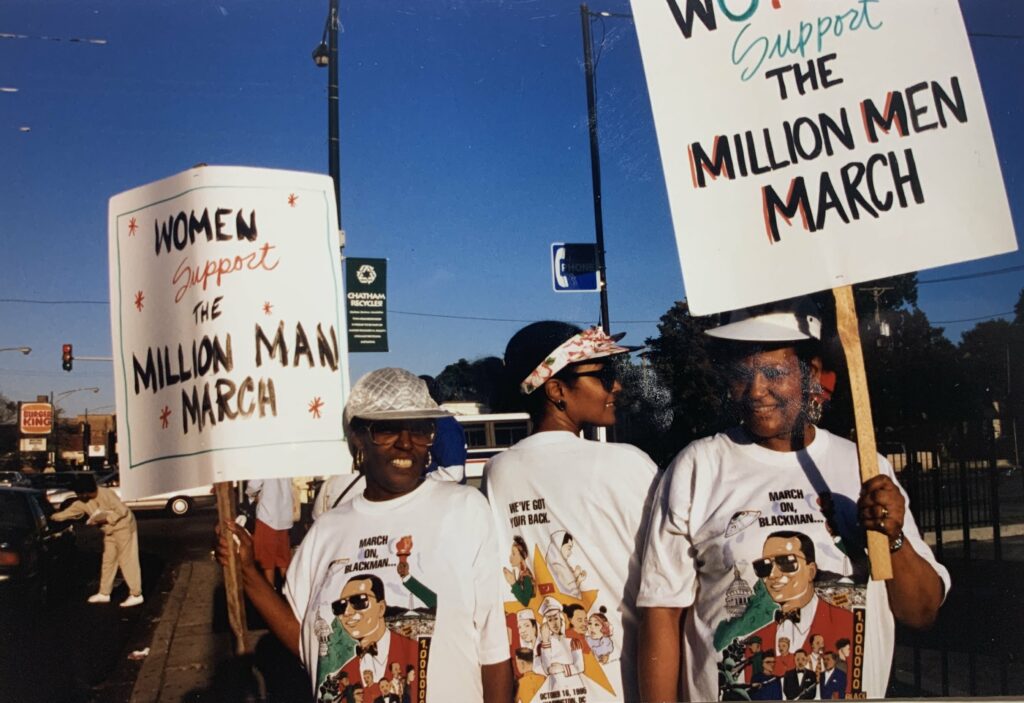

Fredrica Bey, who played a significant part in organizing the March in Newark, N.J., established a successful organization, Women in Support of the Million Man March (WISOMMM). “I said to Minister Farrakhan if you never do anything else in life, the March was so profound. It was organized, so, so, well,” she said.

“The March inspired us to purchase a $5 million property in downtown Newark where we taught many children and held many community events that impacted the community. Minister Farrakhan told me what to expect. He said, you are a black spot in the middle of white development, and they are coming after you. They’re going to come after you with a vengeance. And your only solace will be to wrap yourself in God, you and God, you and God.”

In terms of the legacy of the March and its application today, Ms. Bey pointed to atonement, reconciliation, and responsibility.

“The power of the title, you know going within. We know what the devil did. We know what he continues to do, but we don’t have to continue his legacy. We are the owners, the makers, the God of the universe,” she said.

Harry Spike Moss, a Minneapolis, Minnesota, activist served as the National Director for Cultural Affairs for the March. “The March sent a clear message that not all of us are in prison, not all of us are addicted, not all of us are laying around and trifling and lazy and not about nothing, that message was sent to the world,” he said.

“That was the first part of the message we sent. We’re still here. Good, strong Black men are still here. And then there’s the winning part. The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan told us all to go home, do something to help people, do something to change the life of our people, do something to put them on the right course as a people. And so many Black men, I would dare say we went somewhere about two million or two and a half million men who were at the March. It was so powerful. So many men returned home and engaged.”

Also involved in the organization of the March was St. Louis-based activist Anthony Shahid. “The message remains the same as 26 years ago. We need to come together, atone for the things we did wrong, focus on family, think about economics. Most of all, to have God in our lives. The pledge we took should be taught in schools. The March was a glimpse of heaven. You can’t even go to a house party today without niggas fighting,” he said.

Mr. Shahid also pointed out one measure of success is that how the March name has been copied. The Million Man March has inspired liked named marches throughout the world, he noted. The worst of which was the Trump-inspired Million Maga March held in January in Washington D.C., where the true nature of White people was put on full display resulting in anarchy, destruction, and death, Mr. Shahid added.

During the 2014 uprising in Ferguson, Mo., a suburb of St. Louis, Mr. Shahid was there in the aftermath of the police killing of unarmed Black teen Mike Brown. He has been a leading figure in the movement for justice that came out of that explosion. In 2015, he was in Washington, D.C., for the March anniversary that focused on families who lost loved ones to police violence and a demanded justice.

“The intentional planning that went into making that day possible is in my opinion certainly relevant for Black men to rise up, mentally, spiritually, socially and economically,” commented Carolyn Seward, founder of Family Workforce Centers of America.

“We are seeing what collaborations for a common goal and cause can do. Yet, we must continue the journey that we are on, we can’t stop fighting.”

Steve Conley, CEO of We Care Worldwide, was over 2,700 miles away in Seattle, Washington, and was not able to make it to the March. “I was so inspired by what I saw on television, and the stories that were shared from the many men I knew that did attend. But when the tenth anniversary happened, the ‘Millions More Movement,’ I took my youngest son with me and it was a great bonding experience for both of us, and we both agreed that we would be a lifetime participant of this movement,” he said.

“I have been listening to Minister Louis Farrakhan since I was a teenager, almost 45 years. I have traveled to many places around the world, while living in three different countries. And the work I have seen the Nation of Islam do in developing Black men and women is second to none. And it has been a constant source of inspiration in my entire adult life.”

“The Million Man March showed Black men in a whole other light. It was peaceful, spiritual and uplifting. It was powerful and I know those that hate us and desire to keep us down, hated to see that day happen. Now the use of drugs and sex is being pushed on us so much that it has become a major distraction, and we are being lured back to sleep,” said Mr. Conley.

“I personally saw the impact that March had on Black men. It was like nothing else in U.S. history. And they saw it too. Brothers are still fighting hard to maintain their sanity against the odds and forces against them. Black men are stepping up as fathers, many times without mothers. This is a movement to make real change among our people. Minister Farrakhan is a beacon of light not just for us, but to the world. He represents Black people like no other. His messages wake you up and makes you want to change your life for the better.”

Ron Gregory, the brother of late comedian and activist Dick Gregory, told The Final Call, “What we saw was what is called critical mass, we saw the force of that day, that resulted in Obama being elected and consecutive movements and marches across the country ever since the Million Man March. It was like a buzzing, humming sound that was created from that moment in time that went out into the universe.

And there’s no way to stop the impact of it. The Million Man March set the stage of how a gathering should take place. And it was even compared to what happen on January 6, 2021. But what they did with smaller numbers has disrupted a whole nation and that’s exactly what happened when the two million men came together. That disrupted the country’s power over us. We will never be the same!” declared Mr. Gregory.

Anthony and Angela Muhammad of the Nation of Islam mosque in Washington, D.C., produced a documentary, “The Million Man March: The Untold Stories.” They stressed the importance of Black people documenting their history, and creating accurate narratives.

“What our documentary does is bust the myths concerning the March, that Black women were not behind the March, the Black church did not support the March,” said Angela Muhammad.

The documentary discusses with Minister Farrakhan his thinking behind organizing and his post-March World Friendship Tour.

“The documentary will allow us to celebrate and study the March 360 days a year rather than only on Oct. 16, in the actual voices of those who participated,” said Angela Muhammad. Her documentary was part of a program and discussion on the March anniversary date and can be seen on KweliTV online.

Perhaps the most precise assessment of the March and its aftermath was observed by entrepreneur, author, political analyst, and social commentator Dr. Boyce Watkins. “The Million Man March is probably one of the greatest events and achievements in the history of Black people in this country and around the world. It only further solidified that the Nation of Islam is the premier model of Blackness, aspirational Blackness in the 21st and 22nd centuries,” he said.

“It’s the benchmark against which any and all other events is compared in our community. You can’t name anything that’s happened since 1995 that matches the Million Man March.”

“The March was ahead of its time. It’s just something that I think the world has yet to fully digest the magnitude of the ideas presented at this event,” Mr. Watkins continued. “It makes perfect sense that the enemy would want to marginalize the Million Man March because it wasn’t about integration or these loosely defined concepts, like equality.

It was about building the Black man and the Black woman up to be a competitor in this world. It’s not (White America’s) job to celebrate the March on their media outlets and teach it in their schools; it’s our job to do that. And I believe that we are up for that job.”

A critical aspect of the nuts and bolts organizational aspect of the March was establishing the Local Organizing Committees (LOC), Regional Organizing Committees (ROC) and National Organizing Committees (NOC) throughout the country. Min. Farrakhan crisscrossed the country meeting with community leaders, religious leaders, business leaders, activists and political leaders.

Among those organizing, leading, working and supporting the March were Maulana Karenga, founder of Kwanzaa and the organization Us; Haki Madhubuti of the Black Arts Movement and Third World Press; Dr. Benjamin Chavis, March national director; academic Dr. Cornel West; Dr. Conrad Worrill; and women like Dr. Dorothy Height, a civil rights legend; broadcaster Bev Smith; Atty. E. Faye Williams; Barbara Skinner, community and political activist; Cora Masters Barry, first lady of the District of Columbia;

Mayor Marion Barry of Washington, D.C.; George Curry, of the NNPA Black Press of America; Rev. James Bevel, strategist for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; Leonard F. Muhammad; Claudette Marie Muhammad; Final Call editor James G. Muhammad; Supreme Captain Abdul Sharrieff Muhammad; Student Minister Ishmael Muhammad and Nation of Islam officials and ministers and Believers.

“It is particularly important that we not only remember it but do our very best to revive the spirit of the Million Man March when you consider we were able to do the impossible of bringing together all of the various segments of our community,” said the Rev. Willie Wilson, in a previous interview. He was co-chair of the Washington, D.C. Local Organizing Committee.

(Final Call staff contributed to this report.)

With the Washington Monument in the background, participants in the Million Man March gather on Capitol Hill and the Mall in Washington Monday Oct. 16, 1995. Tens of thousands of black men from across America gathered at the base of the Capitol, and the Mall, in a rally of unity, self-affirmation and protest. (AP Photo/Mark Wilson)

With the Lincoln Memorial in the background, West Coast members of the Nation of Islam gather on the Mall in Washington Monday, Oct. 16, 1995, for the Million man March. Tens of thousands of black men from across America were to gather at the base of the Capitol in a rally of unity, self-affirmation and protest. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

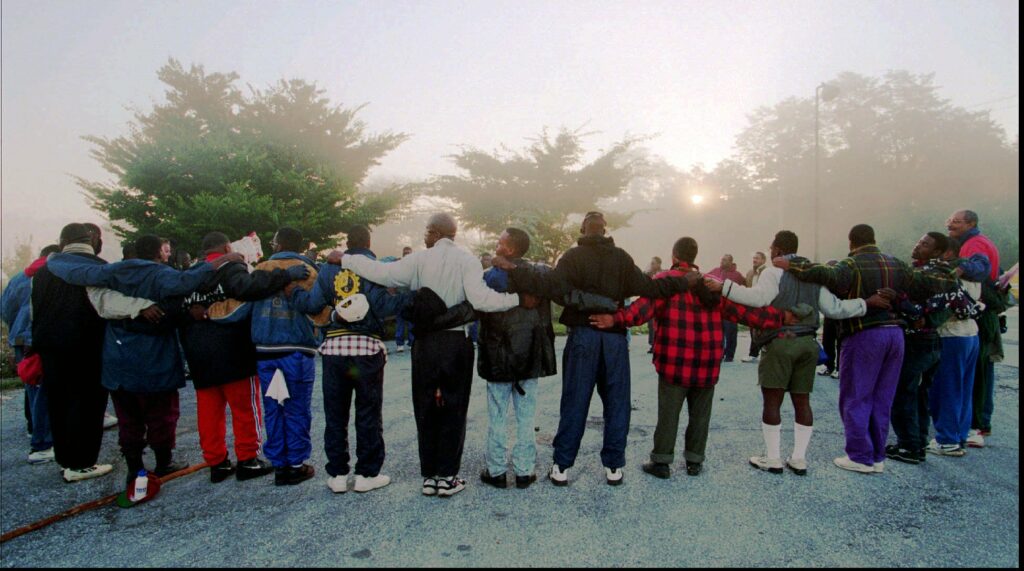

A group of members from the the Greater Germantown, Pa., Turn It Over-Recovery Coalition of America pray together at sunrise near their campsite in Kennett Square, Pa., Thursday Oct. 12, 1995 as they prepare to embark on day two of their march on foot to Washington for Monday’s Million Man March. They are all black men except one white man and all are recovering addicts except one man who was not a recovering addict but who said he hoped to represent Vietnam Veterans who could not be at the March in Washington. (AP Photo/USA Today,Eileen Blass)

Photo taken from the Washington Monument toward the Capitol shows participants in the Million Man March in Washington Monday Oct. 16, 1995. Tens of thousands of black men from across America gathered at the base of the Capitol in a rally of unity, self-affirmation and protest. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

With the Washington Monument in the background, participants gather on the Mall in Washington Monday Oct. 16, 1995 for the Million Man March. Tens of thousands of black men from across America gathered at the base of the Capitol in a rally of unity, self-affirmation and protest. (AP Photo/Doug Mills)