by Naba’a Muhammad and Michael Z. Muhammad

Political prisoners in American prisons have been the source of debate for many years. And while the United States has denied their existence, Blacks, Native Americans and others who questioned, organized and fought the evils, genocide and bloody, deadly repression meted out by the government have found themselves locked away.

Today many of the freedom fighters from the days of the Black Power, civil rights movement and American Indian rights movements remain imprisoned, sick, some dying and the U.S. government refuses to release them.

“The existence of political prisoners in the United States goes to the very heart of the racist nature of this society. To not deal with the issue of political prisoners in the U.S. is to not deal with the true nature of America,” Dhoruba Bin Wahad, a former Black Panther, Black Liberation Army co-founder, and political prisoner targeted in New York and jailed for 19 years, once observed.

An Aug. 19 online discussion focused on the experiences and realities of current and former political prisoners while discussing a tribunal planned for October to again highlight their plight and increase organizing efforts around their cases.

The tribunal planned for New York is part of continued grassroots work underway to free political prisoners and continue the struggle against American imperialism, colonialism, racism, and war, according to Black Voices For Peace, which hosted the online discussion.

Veteran freedom fighter and former political prisoner Jalil Muntaqim, now 69 years old, talked at length about the 2021 “International Tribunal On Human Rights Violations & U.S. Held Political Prisoners” planned for October and spearheaded by the Jericho Movement, an organization devoted to obtaining freedom for U.S. political prisoners and exposing their existence.

“This initiative appeals to the international community, including the International Commission of Jurists, to call for special hearings within the United Nations to review the cases of political prisoners and genocide,” Mr. Muntaqim said. He first thought of the need for such a tribunal while locked in solitary confinement. He served 49 years in prison after conviction in the killing of two New York police officers. He was released in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic. He was a member of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army. He stayed politically active during his incarceration.

“The enemy has an outpost in our minds. In many ways, we are duplicitous with America’s violent history because of our silence. This tribunal will celebrate the 70th anniversary of the call by William Patterson and Paul Robeson of genocide against the United States,” Mr. Muntaqim added.

According to the Jericho Movement, among political prisoners on lockdown today is Ruchell Magee, who was denied parole again in June. He is the longest-held political prisoner in the United States and the world, serving time in California prison system for over 57 years. He is 81 years old.

He has served time related to the 1970 Soledad Brothers case and the attempt of 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson to free his brother George Jackson and others who were on trial and accused of killing a prison guard. Mr. Magee was also freed but San Quentin prison guards eventually shot three of the accused and critically wounded Mr. Magee survived. He was later convicted of simple kidnapping.

“People have committed horrendous crimes and gotten much less time than Ruchell. Mention that Ruchell was very young when he was arrested and he should be able to enjoy the rest of his life outside of captivity. Add that we as taxpayers pay to keep this elderly man incarcerated instead of in his community, where he could make a positive contribution toward community development,” said the Jericho Movement in an appeal for his release.

Others include Dr. Mutulu Shakur, who was sentenced to 60 years in prison and targeted by the FBI’s now-infamous Counter-Intelligence Program as early as 1968. “Dr. Shakur has served over 30 years in prison, and is currently suffering from multiple myeloma (advanced bone marrow cancer). He has been denied parole nine times and was recently denied a compassionate release,” said the Jericho Movement. His family and friends are mounting a campaign to petition President Biden to grant clemency in the case.

“Russell Maroon Shoatz, a 77-year-old political prisoner, is suffering from stage 4 cancer,” said the Jericho Movement. His is another political activist jailed for his role in the Black liberation struggle say those who want him released.

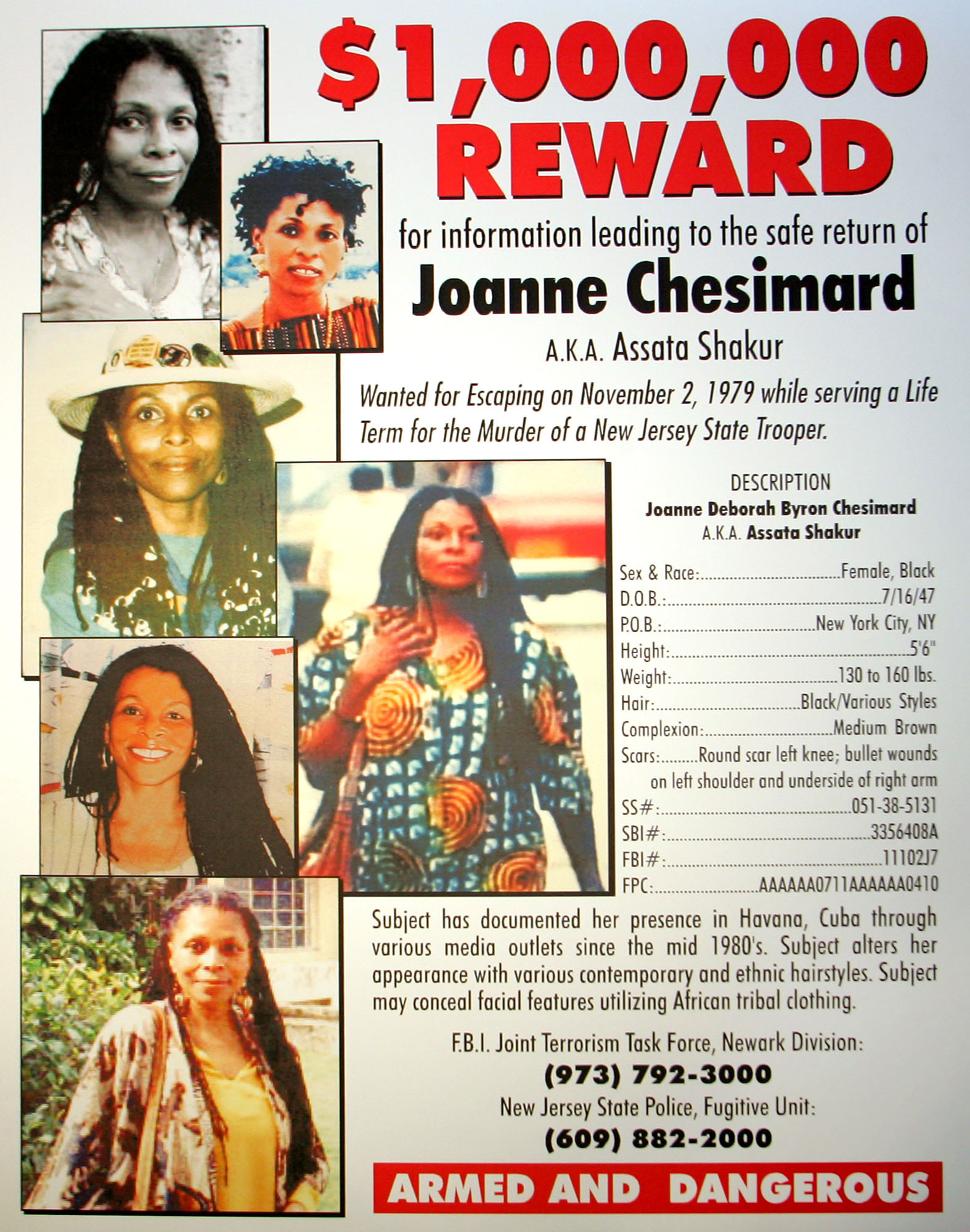

Among political prisoners listed today by the Jericho Movement are Abdul Aziz, Haki Malik Abdullah (formerly Michael Green), Sundiata Acoli (formerly Clark Squire), Imam Jamil Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown of the Black Panther Party and Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee), Joseph Bowen, Veronza Bowers, Kojo Grailing Brown, “Muhammad” Fred Burton, Byron Shane Chubbock, Bill Dunne, David Gilbert, Hanif Shabazz Bey, Alvaro Luna Hernandez, Kamau Sadiki, Larry Hoover, Abdullah Malik Ka’bah (formerly Jeff Fort), Maumin Khabir, Eric King, Malik Smith, Marius Mason, Leonard Peltier, Ed Poindexter, Rev. Joy Powell, Jessica Resnicek, and Mutulu Shakir. Not to be forgotten are those who fled America and remain in exile like Assata Shakur in Cuba.

“There are hundreds of people who went to prison as a result of their work on the streets against oppressive conditions like indecent housing and inadequate or complete lack of medical care, lack of quality education, police brutality and the murder of people organizing for independence and liberation,” the Jericho Movement noted. “These people belonged to organizations like the Black Panther Party, La Raza Unida, FALN, Los Macheteros, North American Anti-Imperialist Movement, May 19th, AIM, the Black Liberation Army, etc., and were incarcerated because of their political beliefs and acts in support of and/or in defense of freedom.”

A young vanguard of Black freedom fighters spoke during the “From Black August to Black Liberation Commemorating the Struggle of Political Prisoners” webinar convened by the Black Alliance for Peace.

The virtual event was hosted by Nnamdi Lumumba of the alliance.

Longtime activist Makungu Akinyela and a founding member of the New Afrikan People’s Organization said over the years he realized “everybody wasn’t going to always be professional revolutionaries. So in 1990, we established the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement with the idea that the masses of our people needed a platform that they could organize under. That they could organize around principles of self-determination, human rights, fighting against genocide, fighting for the freedom of all of our people, regardless of gender, sexuality, or sexual identity fighting against sexist oppression.

“And then, of course, we saw it as important to support our political prisoners,” he said.

Black August is a month-long commemoration and prison-based holiday to remember Black freedom fighters and political prisoners and highlight Black resistance against racial oppression. It began to be popularized through hip hop concerts among young people.

“A central element of Black August is to call attention to our freedom fighters still held captive as political prisoners and Prisoners of War. Some have moved into their fifth decade shackled as the longest serving political prisoners on the face of the Earth,” observed the Black Alliance for Peace.

“We believe Black August is about uniting the masses of our people with the idea that there are political prisoners. They are prisoners of war, brothers, and sisters who were willing to take up arms in self-defense of our people’s struggle, and they deserve to be supported and not run away from,” said Mr. Akinyela.

A young voice on the scene is Philadelphia-based activist, scholar, and educator Krystal Strong, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She detailed the plight of the MOVE organization and the lessons learned. She noted that August 8, 1978, was the date Philadelphia police besieged the Black radical group’s compound resulting in the arrest of 12 people, including the Move 9, members sentenced to prison for 30 to 100 years.

“What is lost in all of the noise is histories untold and underappreciated in our Black revolutionary struggles,” Ms. Strong said. “We define this radical revolutionary work by stories of state bias. What we don’t understand is the revolutionary work of these organizations. MOVE’s protest against the Philadelphia school board against educational injustice, their protests at the Philadelphia Zoo against animal cruelty, the revolutionary vision for respect towards all life, food justice, exercise, to being in proper relationship with the planet.”

“And so one thing that I think MOVE’s history makes very clear to us, particularly the history of political imprisonment, is that political incarceration detracts from our revolutionary strivings,” she said. “The fact that we know more about state violence against MOVE than what MOVE’s radical visions were is a testament to the intended impact of political incarceration.

“Another thing this illuminates for us is that political imprisonment creates further harm. It spreads harms even beyond our beloved community members and revolutionaries who are incarcerated,” Ms. Strong pointed out.

Another young presenter was Saudia Durrant, a Philadelphia-based racial justice organizer with the Abolitionist Law Center and the Jericho Movement. She brought fire and intensity in her presentation reminiscent of old-time church religion. She talked about her work with young people, demands for police-free schools, sanctuary schools free of agents from the federal government’s Immigration, Customs and Enforcement agency, and empowering young people to be community leaders.

“Our mission is exposing, challenging, and dismantling the American punishment system. And we do this in solidarity with our comrades, putting down this grassroots effort with other cities. We fundamentally believe in doing this work to build the capacity to abolish these institutions and the social constructs that attempt to legitimize the presence of state violence. And believe our communities can create new methods of dealing with these issues while politicizing our communities for self-defense, self-determination, and independence,” she said.

“We say, educate, organize, agitate, liberate. The idea is clear that whatever we are attempting to do, it begins with education and it ends with liberation.”

Many of the activists paid homage to Min. Malcolm X as the inspiration for their work. His teacher, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, taught Min. Malcolm and others sparking a revolutionary mindset, a desire for full and complete freedom, and a nation for Black people. The Hon. Elijah Muhammad was also a political prisoner, jailed for his teaching against the wickedness of the American government during WWII.

His top student, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, has continued to teach about the wickedness of America, warned of her destruction, and exposed her warmongering, lies and wicked foreign and domestic policy. He has also defended and supported political prisoners in the United States.

“Sacrifice is the unselfish giving of what one needs for oneself to accomplish an end that is greater than oneself. The scriptures of the Bible and Holy Qur’an are full of examples of sacrifice,” said Min. Farrakhan in an address delivered during a benefit for then-political prisoner Geronimo Pratt, a Black Panther Party leader who was eventually released after over 20 years in prison for a murder he did not commit.

“It is not enough to praise Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Nat Turner, Nobel Drew Ali or any of our brave freedom fighters. What we must do is take the principles that they lived and died on and be willing to sacrifice to see the end for which they lived and died. Then, and only then, will our living not be in vain and their sacrifice not have been in vain,” the Minister said.

“There never has been a teacher of valid principles for the liberation and survival of Black people in this country who has not been persecuted by the United States government, maligned, falsely accused, vilified by this system,” he continued. “Many criticized Elijah Muhammad, calling him counterrevolutionary, because they did not truly understand revolution, but romanticized about it. The root of revolution is light.

There is no motion without light. Light causes the motion of our planet. This planet makes its revolution around the sun by the power of light striking Earth at its equator, causing Earth to spin and producing the four seasons. The introduction of light and knowledge to a people who are asleep under the foot of oppression causes an idea of revolution to germinate in their minds. There is no revolutionary who is worth his salt or his sense that throws away his life. He wisely maneuvers in order that the revolution may live.”

“Malcolm X was not a revolutionary until he met the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. He was like most of us, wanting something better, but not knowing how to go after it. Many of our people said the Muslims just want to talk and sell papers. But Muhammad was wise; he said, ‘Yes, Brother, for now.’

How can we build a revolution without the idea of that revolution in the heads, hearts and minds of the people? How can we get Black people to make a sacrifice for an idea when we do not trust each other? We have to build a record of trust among our people, which means you have to adopt principles that encourage and promote trust.

“So the revolutionary that he was, he said, ‘Let me direct your anger to something within you that is counterrevolutionary’—but he did not call it counterrevolutionary. He simply said let me direct your anger to something in you that is against the rise and liberation of our people.”

And Min. Farrakhan added, “We encourage this suppression by our unwillingness to sacrifice, discipline and organize ourselves properly against an oppressor and for our own liberation.”

Ms. Durrant put forth four strategies being used to free political prisoners, including clemency, commutation, parole, and overturning wrongful convictions.

“Communities must be organized to demonstrate solidarity, be it through marches, rallies, community meetups, and cleanups, art in cultural performances, organizing media content, and many other tactics to publicize the movement,” she said.

Ending her presentation, Ms. Durrant discussed the dire medical conditions facing political prisoners like MOVE member and former Black Panther Mumia Abu Jamal, former Black Panther Russell Maroon Shoatz, and Native American activist Leonard Peltier. “These are the mentors and the leaders of our movements of our communities who languished behind bars. We know that our folks are suffering inside, and we must honor them and commit to not leaving them behind,” she said.

During the question and answer segment, threats confronting organizers were addressed.

“We do not have reserves for when the state inevitably targets us. We need to out-organize our enemy. We have to learn from these histories. We have to be a part of collective networking, particularly around the threat of political imprisonment. We need to develop and share protocols that exist. You know, many of us are on signal. Still, signal is not enough of a strategy to out-organize the enemy that is in our bedrooms, our living rooms,” Ms. Strong observed. “We need to up the ante around things like protocols and safeguarding to the extent that we can.”