One hundred years after a deputized White mob looted and obliterated businesses and places of worship, dragging families from their homes as they burned in the middle of the night in the Greenwood community of Tulsa, Okla., known as “Black Wall Street,” the massacre, whitewashed from many history books, is now being viewed by many as the dreadful decimation of human life and property that it was.

It’s called the Tulsa Massacre. The victims remain uncompensated for their losses and the perpetrators were never prosecuted for their crimes. An estimated 300 people were killed within the district’s 35 square blocks, burning to the ground more than 1,200 homes, at least 60 businesses, dozens of churches, a school, a hospital and a public library, according to a report issued by Human Rights Watch.

Residents claimed at least $1.4 million in damages after the massacre, or about $25 million in today’s dollars after controlling for inflation and the current economy, but experts say it’s an underestimation. Many insurance claims filed by the Black victims were denied. The opportunity for Black multi-generational wealth for Black families was decimated as a result. Survivors were denied U.S. government assistance or restitution for their losses. Experts call it the single-most horrific incident of racial terrorism since slavery.

“We have a tendency to view events as though they happen in a vacuum. What Tulsa gives us is a link to the racist mindset that was in existence in 1921 and it’s the same mindset that exists today,” political commentator Dr. Wilmer Leon told The Final Call. “We’ve been fighting this same fight since 1619, and Tulsa is just one data point in a litany of data points that show it’s an ongoing—as they would say in the Rico statutes—it’s an ongoing criminal enterprise,” he said. “Charlottesville is an example of the ongoing criminal enterprise, Dylan Roof shooting up Mother Emanuel Church is a data point in the whole argument of the ongoing, criminal enterprise of racism in America,” continued Dr. Leon, reflecting on a White supremacist rally in 2017 and the 2015 slaughter of nine Black parishioners during a Bible study gathering.

“Why we continue to have these problems is because nobody wants to admit them, and nobody wants to deal with what those realities mean. It’s like an alcoholic saying I’m going to do everything in my power to turn my life around, but I won’t stop drinking. Greenwood is incredibly important, not only because it happened, but because the government refuses to compensate those victims of it.”

A past and present tied together

On May 31, 1921, Tulsa police arrested 19-year-old Dick Rowland, for allegedly assaulting a White girl. There was little evidence or proof he was guilty of any crime. Like today, in 1921 media was quick to write an editorial calling for the young, Black man to be lynched.

“A group of Black World War I veterans tried to achieve justice for the young man whose life was threatened at the courthouse from a gathering lynch mob,” Frederick Al Deen of the Greenwood Policy Institute told The Final Call.

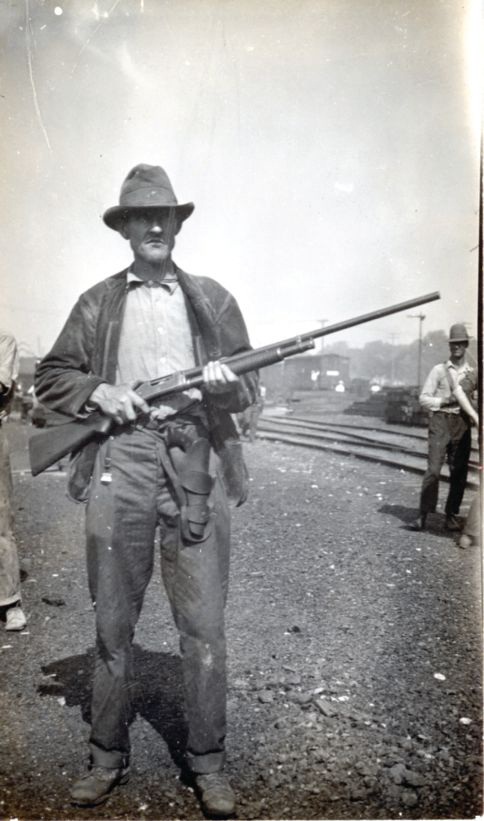

The sheriff told the Black men to leave. They did but the White mob grew to over 2,000 and the sheriff did not tell them to leave. The armed Black men returned later.

“They were met by a large mob of White citizens, militia, and others bent on lynching. A fight broke out and shooting started. The question is once those people found themselves fighting the police authorities and eventually the Air Force who dropped bombs, who do they look to for justice? That is the same question we have now with qualified immunity,” said Mr. Al Deen.

Qualified immunity is a major point in police reform today. Qualified immunity established by the Supreme Court in 1967, effectively protects state and local officials, including police officers, from personal liability unless they are determined to have violated what the court defines as an individual’s “clearly established statutory or constitutional rights.”

This is why many police officers are found not guilty in trials where they are accused of wrongfully killing someone. It is a point of contention in the current George Floyd Justice in Policing Act that has yet to pass the Senate.

In the early hours of June 1, then-Gov. James B. A. Robertson of Oklahoma declared martial law and called in the National Guard. Together with local law enforcement, they deputized White citizens to go door to door in Greenwood to disarm, arrest and move Black people to internment camps, forcibly dragging many out of their homes.

As the fighting lasted for hours many Blacks ran for their lives and escaped capture. According to the Human Rights Watch (HRW) report titled, “US: Failed Justice 100 Years After Tulsa Race Massacre—Commission Alienates Survivors; State, City Should Urgently Ensure Reparations,” once in the camps, Black Tulsans were not able to leave without permission of White employers.

When they did leave, they were required to wear green identification tags. By June 7, 7,500 tags had been issued. The American Red Cross, which ran the internment camps, reported that thousands of Black Tulsans, then homeless, were forced to spend months, or in some cases over a year and through the winter, in the camps, in tents.

“I had everything a child could need,” Viola Ford Fletcher, 107, told The House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties hearing May 19, on the Tulsa Massacre.

“The night of the massacre, I was awakened by my family. My parents and five siblings were there. I was told we had to leave and that was it. I will never forget the violence of the hate mob when we left our home. I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street. I still smell smoke and see fog. I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams. I live through the massacre every day. Our country may forget this history, but I cannot.”

The Tulsa City Commission issued a report two weeks after the massacre saying: “Let the blame for this negro uprising lie right where it belongs—on those armed negros and their followers who started this trouble and who instigated it and any persons who seek to put half the blame on the white people are wrong …”

A failed justice system has prevented the perpetrators of the Tulsa Massacre from prosecution.

The HRW Report found that one of the only indictments that was pursued was that against John Gustafson, the White Tulsa police chief who was accused of neglect of duty, and charges unrelated to the massacre—freeing automobile thieves for which he collected rewards.

After a two-week trial that garnered significant press attention, he was convicted, sentenced to a fine, and fired. According to James Hirsch, who wrote a book about the massacre and its aftermath, Gustafson’s conviction had the effect of granting “blanket immunity” to all the White people who murdered and looted.

In charging Gustafson, the prosecutor made clear that she did not believe any of the White people who armed themselves had violated the law. That pattern and practice continues today in the face of ongoing assaults against Black people.

Tulsa was not the only Black town invaded and destroyed by angry White mobs. In 1919 Black farmers in Elaine, Arkansas met to establish the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America to fight for better pay and higher cotton prices. They were shot at by a White mob. The farmers defended themselves and returned fire. News of the fire fight spread and the Blacks were massacred, leaving more than 100 (estimates up to 800) Black farmers dead, 67 indicted for inciting violence, and 12 Black sharecroppers (the Elaine 12) sentenced to death.

Between 1917 and 1923, more than 1,100 Americans were killed in such racist attacks, according to William Tuttle Jr., a retired professor of American studies at the University of Kansas and author of “Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919,” noted a recent article in USA Today. That violence continued over the course of 10 months in 1919 when more than 250 Blacks were killed by White mobs in at least 25 riots across the country, the article continued. Major attacks took place in San Francisco; Chicago; Wilmington, Del.; Macon, Ga.; Knoxville, Tenn.; Rosewood in Fla. and many other cities and towns. On January 1, 1923, the small town of Rosewood was destroyed and the people massacred after it was rumored a White woman named Fanny Taylor, had been sexually assaulted by a Black man in her home in a nearby community. A mob of White men, believing this alleged rapist to be a recently escaped convict named Jesse Hunter was hiding in Rosewood, assembled to capture him. They burned homes, businesses, lynched men, and killed women while people ran for their lives to hide in the swamps. When the slaughter and destruction was over, only two buildings remained standing, a house and the town general store.

Looking forward

Dr. Leon explained that what happened in Tulsa brings to account the issue of reparations. “You can’t move forward until you atone. It’s impossible. You can’t get to heaven until you say my Lord, I’m sorry. You can’t, it can’t happen. This is very, very important. It also gets to the whole issue of critical race theory and this foolish debate about whether or not critical race theory should be taught or used as a foundational element of teaching history,” he said.

“It was really the destruction of the northern side of Tulsa,” Dr. Haleem Muhammad, an urban planner, told The Final Call. “They destroyed the whole community. Thousands of homes, hundreds of businesses, and places of worship. They killed Black professionals. They rounded us up by the hundreds and thousands. They placed us in a convention center and the baseball field, and then the fairgrounds,” he said. “Then they not only burnt down, but they looted before they burnt down. They used the National Guard. They used the police, they use White mobs that were deputized by the law enforcement. They dropped explosives on us from airplanes. Then we eventually rebuilt portions of the Greenwood portion of Tulsa, but then they ran a U.S. Highway 75 through there and cut it in half. So they destroyed it twice,” said Dr. Muhammad, who servers as the Southwest Regional Representative of the Nation of Islam.

“Having just visited Tulsa just a few weeks ago, the Greenwood Center there can either be our inspiration to rebuild portions of Black Wall Street, because the most Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us—he asks and answers the question: ‘Do we have the qualified men and women for self-government?’” he said, referring to the Nation of Islam patriarch.

“The answer is yes, we have the city planners. We have the architects, we have the civil engineers, we have the millionaires and the billionaires. We have the construction people. We have everything we need to rebuild Black Wall Street,” he explained.

“Are we going to be governed by fear or faith? When are we going to get together after this 100-year commemoration and rebuild portions of Black Wall Street so they won’t be just something that reminds us of some evil that was done to us?”

In the legacy of Black Wall Street and other independent Black towns a resurgence is taking place in some parts of the country. In the aftermath of the killings of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia and other Black people around the country, 19 families in Georgia purchased nearly 100 acres of land and later an additional nearly 500 acres with the goal of establishing a secure place for Black people. “So, we are establishing what we hope will become the city of Freedom, Ga., which is a self-sufficient, safe haven for Black families,” explained Ashley Scott, one of the founders of the Freedom Georgia Initiative.

Around the country a range of programs commemorated the 100-year anniversary of the Greenwood Massacre. In Tulsa there was a march, an unveiling of a memorial, dedicating a pathway to hope and a Black Holocaust Remembrance/Reparations Night. The production company of NBA star LeBron James produced a CNN special, ‘Dreamland: The Burning Of Black Wall Street.’ The Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN) aired a two-part special event OWN Spotlight: The Legacy of Black Wall Street that explored the rise and fall of BlackW all Street.

In St. Louis, Mo., the Universal African Peoples Organization (UAPO) sponsored an event called, “In the Spirit of Malcolm X.” “Our program started with words of solidarity and prayer, and then an African drum call in the spirit of the ancestors. We had poetry from some of our local poets, Robert Wise, Coffee Wright, Rosco Ros Crenshaw and Rachel Simone sang Strange Fruit, by Billy Holiday,” said Zaki Baruti, president of UPAO.

(Final Call staff contributed to this report.)