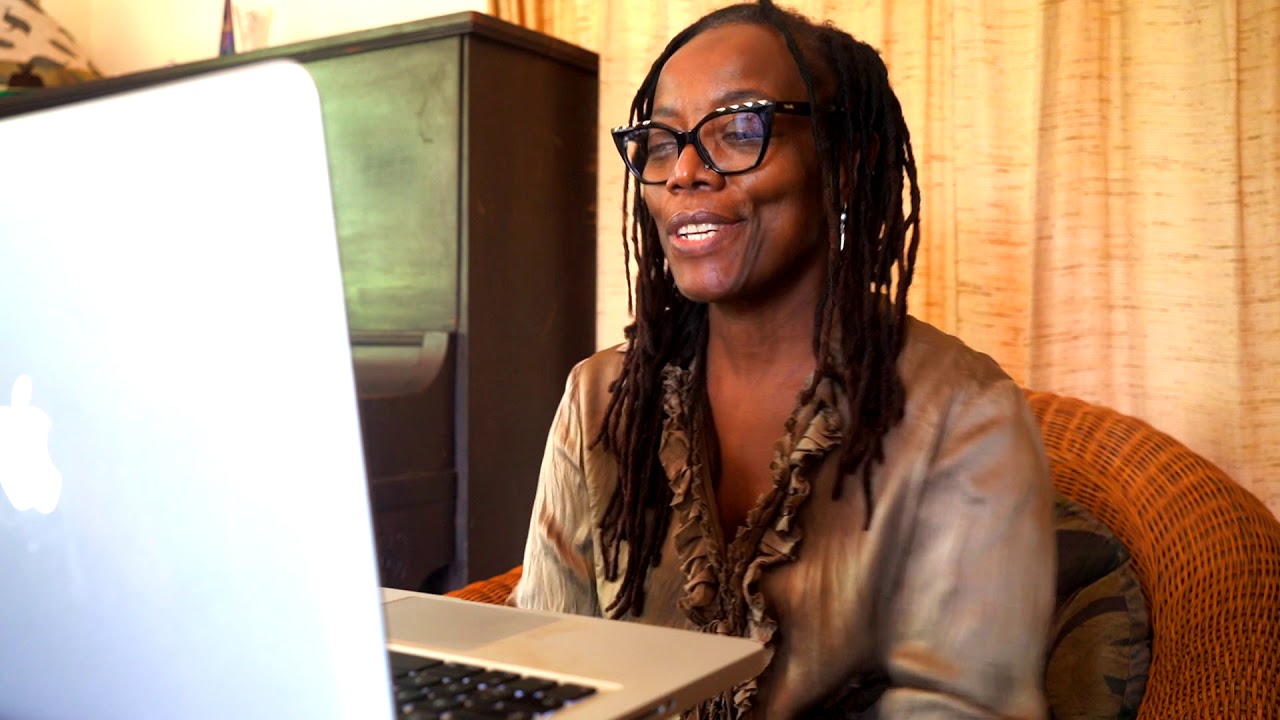

Writer, film maker, playwright and activist Tsitsi Dangarembga recently appeared on BBC’s HARDtalk with host Zeinab Badawi. The 62-year-old Zimbabwean is one of Southern Africa’s most acclaimed cultural figures.

Jailed for her political activism at one point, the content creator says her art provides a platform for her activist views and an opportunity to be listened to when she calls for change.

Questioned about her latest novel, “Mournable Body,” which focuses on female character Tambudzia, Dangarembga said: “I find generally my work intersects between the personal and the national and the historical because the national and the historical have a lot to do in determining what the person can do, what the character can do—whether this is in real life or a novel.

I do want my work to be realistic. … I had wanted people in Zimbabwe and on the continent to engage from a perspective of recognition to say, ‘Yes, this is us.’ Also I wanted to present characters like the people I met to the rest of the world.”

In “Mournable Body,” Dangarembga returns to the protagonist of her acclaimed first novel, “Nervous Conditions,” to examine how the hope and potential of a young girl, her fight against all forms of prejudice and a fledging nation can sour over time and become a bitter, floundering struggle for survival.

Discussing the country’s post-colonial history, she said she felt the period of history when Robert Mugabe was in power was a time of increasing disillusionment and lack of hope and distress.

She told HARDtalk host Badawi the post-colonial Zimbabwe of 1980 up until and beyond 1990 went fairly well. “But then things began to disintegrate. Daily life is almost impossible for most of the citizens in the country.” This includes, she added, “getting enough food to eat, being able to afford to buy food, having power in your home and clean water. All of these things are not things you can anymore take for granted.”

But even with the 2017 departure from office and the death of the former freedom fighter and president, she admitted, “It’s been a great decline since the days of Robert Mugabe. And going forward from the time of Robert Mugabe we do not see that has been any improvement.”

She also reflected on the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and the guerilla war for liberation from White minority rule when the country was known as Rhodesia.

“I remember being in Harare in 1980 when ZANU-PF won the election and just seeing people screaming (for joy) in the streets. This came after a war that lasted for 15 years.” Dangarembga said. The entire majority Black population, she said, “one way or another participated in the war.” She said average citizens “engaged with the guerrillas. They fed them, they took them in and hid them from the Rhodesian forces onslaught.

People contributed money and other resources to the war effort. So it felt like we had (all) managed to do something good for ourselves for once, all together as a nation. And we were going to go forward in the same way. It seemed like for the first time we had made our own history. Because during the colonial era history was made for us by other people.”

Still today, said the writer, “We are living at the very edge of survival. It’s like the proverbial drowning person clutching at a straw. Anything is available to us to improve the quality of our lives we are willing to give something for.

“To give you an example of what I mean: We’ve been through (pandemic) lockdown which means that young people have not been at school. It means young girls on the streets just trying to help their families to survive. And young girls engaging in transactional sex maybe as early as 12 or 13 years of age. What kind of money are these girls receiving as payment? Sometimes what they receive is vegetables so they can provide a meal for their families.

This is the nature of the transactional life that we have lived. Everyone looks at the next person as a person from which something can be gained, something that is necessary for continuing to live and getting through the day. We no longer look at each other as co-nationals with a common history, a what can we do to construct a common fate. It’s about what can I get out of this person in this situation at this moment in time, or how something can be gained,” Dangarembga said.

Not surprising, her HARDtalk 22-minute interview, like most Western media outlets, didn’t tell the whole story. It doesn’t focus on how Zimbabwe got to where it is with broken UK and American promises and U.S. sanctions still in place against the Southern African nation.

British and U.S. violations of land reform measures agreed to during negotiations to end the liberation war eventually led to the demise of Robert Mugabe and ZANU-PF aspirations. Western media outlets generally never speak of the involvement of former colonial master Great Britain and her American allies, nor the neo-colonial relationship and economic dependence Zimbabwe had on her former colonizer even after “independence.”

Reginald L. Streater, Esq., wrote in 2019 about land reform—the government taking valuable farmland held by minority Whites and giving it back to the Blacks it was taken from. Zimbabwe wanted to “break the chains of colonialism” and enjoy “self-determination and land reform under international law,” he wrote.

ZANU-PF’s inclination during 1979 independence negotiations, held in the UK and known as the Lancaster House agreements, was an unwillingness to have Zimbabwe pay Whites for “stolen ancestral land.”

ZANU-PF declared: “If this London conference reaches no decisions, we will dispatch our military men back to Africa. This means intensification of the struggle. We can win without Lancaster House. That is a certainty. Of course, we would welcome a settlement. But we can achieve peace and justice for our people through the barrel of a gun.”

Only after “oral” assurances Great Britain would shoulder much of the financial burden, along with a pledge from the U.S., did ZANU-PF acquiesce to “vague, promises of assistance.”

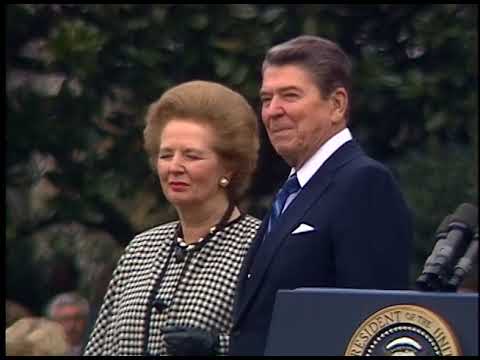

The Lancaster negotiations would not have succeeded if Great Britain had not offered to pay for land reform. It was a surprise during the last leg of talks with UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government.

“The representatives found themselves confronted by an uncomfortable compromise that would commit them to respecting existing European property rights and debar them from any expropriation of land during the first 10 years of independence,” according to the UK-based Independent newspaper.

The Lancaster accords were largely shaped by British interests. It was a way to get back into the life of its former colony. The constraints on land reform imposed also deprived Zimbabweans of the rights to self-governance and self-determination other nation-states enjoyed.

UK-U.S. verbal promises were eventually violated, leaving Zimbabwe to this very day in a vulnerable position.

After the UK and U.S. refused to make good on promises to pay Whites for land stolen from Blacks in Zimbabwe, it took decades for the Mugabe government to expropriate the land. Western nations balked and eventually instituted sanctions, charging political wrongdoing and other issues, cut aid and demanded the ouster of Mr. Mugabe. That happened in 2003. But sanctions have not been removed and U.S. aid has not increased. The U.S. continues to accuse Zimbabwe of rights violations and Zimbabwe has continued to suffer and decline.

Last year, Zimbabwe officials expressed dismay at U.S. decisions to extend the sanctions. “Once again the government of the United States has chosen to strangely characterise Zimbabwe as a country that poses an extraordinary threat to the foreign policy of the United States,” said Zimbabwe’s president, according to March 2020 reporting by Al-Jazeerah.

The president, Al-Jazeerah said, blamed “the sanctions imposed by the U.S. and the European Union for Zimbabwe’s economic ills and says they are intended to remove his ZANU-PF party from power.”

And, it said, the “United Nations special rapporteur on right to food, suggested economic sanctions by the U.S. and the EU against officials and entities linked to the governing party over alleged abuses are contributing to Zimbabwe’s current dire food security situation.”

Last year, the World Food Program estimated over 8.6 million Zimbabweans (60 percent of the population) required food aid from the government and donor community to avert starvation. Starvation levels were also worsened by Covid-19 lockdowns, income losses due to high inflation and increase in poverty levels over the last 24 months. Inflation still remains high at 402 percent a year.

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.