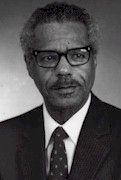

CHICAGO—Black nationalists, activists, Christians, Moors, and Muslims, representing a cross section of Black beliefs, recently met on 37th and Wabash Avenue on the city’s South Side to celebrate, honor and remember Lutrelle “Lu” Fleming Palmer, Jr. a fearless writer, radio show host, newspaper publisher and political activist.

He is remembered for his journalistic skill, organizing and an unforgettable phrase, “It’s enough to make a negro turn Black.”

Mr. Palmer would have been 99 years old this year.

Activists in their 20s to those in their 70s—representing the Nation of Islam, the Moorish Science Temple of America, the United Negro Improvement Association, the Black church, the National Black Agenda Consortium, African American Contractors Association, Ex- Cons for Community and Social Change and others—reflected March 28 on how Lu Palmer used journalism and organized to advance the cause of Black unity and independence.

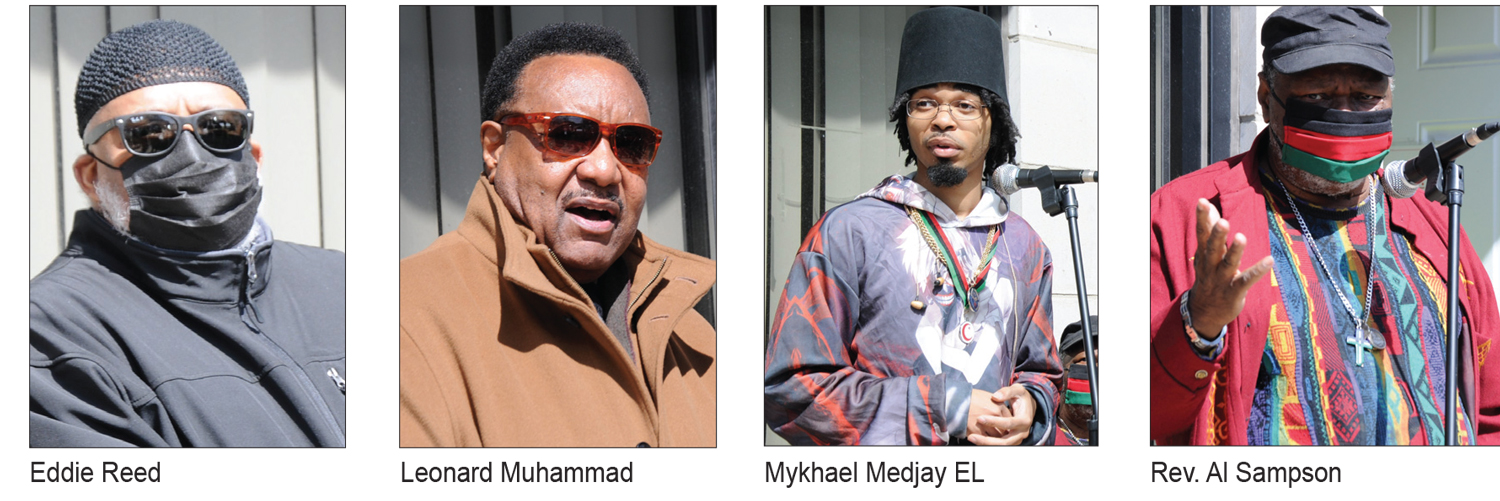

“We are representing Baba Lu Palmer today on his 99th birthday so we are uplifting 99 red, black and green balloons and sending them up to the ancestors,” said Eddie Reed, longtime activist and disciple of Lu Palmer and event organizer.

“This is where it all happened, right here. Harold Washington came through here,” he said pointing to the entrance to CBUC/BIPO headquarters. “This is where the movement started. This is holy ground; this is our Mecca. This is our Vatican.”

Mr. Reed worked alongside Mr. Palmer for many years and since Mr. Palmer’s passing has kept both organizations going—not only focused on the work of the organizations, but also providing a home for other organizations fighting for Black independence.

“The village was very, very well represented. Queen Mother Mary L. Johnson and Elder Queen Eunice Wigfall represented strongly what CBUC BIPO continues to stand for 41years later,” said Mr. Reed. “We are also very pleased that we were joined by a delegation of young individuals.”

“It’s an honor for the Nation of Islam to be here to participate in this occasion. The Holy Qur’an says speak not of those who died in the way of Allah as dead, they are alive, but we perceive not. Today Lu Palmer is alive. To me, the thing that we have to do is quicken our pace to carry out and bring into practice those things that he gave his life for. That’s all of our dedication to him, to Jorja and I pray Allah that we will all be successful in doing that,” said Leonard F. Muhammad of the Nation of Islam.

Two organizations established by Lu Palmer and his wife continue through the work of Eddie Reed. “He’s a fighter, he’s consistent and he’s not afraid,” said Mr. Muhammad as he recognized activist Reed’s efforts to keep the work of the Palmers alive.

Rev. Albert Sampson, a longtime friend, pastor, activist and organizer married Lu and Jorja Palmer. “Like the African drum,” the couple were together helping our community,” said Rev. Sampson. Lu Palmer arrived in Chicago to work at the Chicago Defender in 1950 as a reporter.

He became a syndicated columnist at the Chicago Daily News, which was a leading mainstream publication at the time. He used his pen and his mouth to not only report on current events but also built an institution that helped usher in the first Black mayor of Chicago.

He founded the Chicago Black United Communities in 1979, the Black Independent Political Organization in 1981, and served as chairman of the Extended Services Program for the Group Living Facilities for Boys in 1998. The building that houses the first two organizations sits next to the historic mansion where he and his wife Jorja lived.

Their work continues and the building is home to a new generation of activists and teachers. It was in front of that building that the celebration took place.

“What we are doing here is consistent race work and we are uplifting our people. We are doing the work that nobody else is going to do,” said Mykhael Medjay EL, the youngest grand governor of the state of Illinois within the Moorish Science Temple of America. “I want to thank you Baba Eddie Reed, Baba Maruwa Ferrell for keeping these doors open for brothers like myself.”

Marquinn McDonald, another activist, echoed that sentiment. “I was fortunate enough for the elders to allow me to come to his house. We educate the youth in this house. We feed our people in this house. They allowed me to teach free martial arts lessons to the kids and self-defense classes for women inside this house. Without Baba Lu, whom I didn’t have the pleasure to meet, I would not have this brick and mortar to share the gifts I was given.”

Maruwa Ferrell, who runs the Garvey Center out of CBUC/BIPO headquarters, expressed his appreciation for listening to Mr. Palmer’s “On Target” program on Black talk radio station WVON-AM 1450 as a young teen.

Mr. Ferrell’s father was a disciple of Lu Palmer. “It was because of right here that we were able to get the first Black mayor of Chicago. Palmer coined the slogan ‘We shall see in ’83,’ which became a rallying cry for the election of Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black mayor.

“I’m glad to see you all here. Realize that it is your house, as long as you are Black … this is a safe place for Black people to organize, to build because we need power. We got to have some Black power,” added Mr. Ferrell.

With recent discussions about the film “Judas and The Messiah,” it’s important to note that Mr. Palmer was the first reporter to question the motives behind the 1969 raid on a West Side two-flat in which Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton of Chicago and Mark Clark of Peoria were assassinated.

The day after Hampton and Clark were killed, Mr. Palmer reported a view contrary to the official police line.

“The leadership of the Black Panther Party has been steadily, and some would say systematically, skimmed off,” he wrote. He ultimately left the publication because of “meddling” with his articles, he said. He then founded the Black X-Press Info-Paper.

Many present shared anecdotes about Mr. Palmer. Omar Shareef talked about how he organized 150 men to travel to Atlanta to help look for 21 missing children. “I was a student at Loop College (now Harold Washington College), when Lu organized and brought attention to Atlanta. Lu Palmer was our hub for anything that had to do with the Black movement.”

“I remember a situation way back in the ’90s where there was a lot of division among a lot of organizations and activists and it was Lu Palmer who gathered us all at the Center for Inner City Studies and had us talk it out,” said FX. “Some of them didn’t get ironed out but a lot did and new relationships were formed.

“Lu instilled in me actionable unification. I appreciate Lu as an ancestor for that always.”

There have also been questions around the Palmer mansion. The 133-year-old home at 3654 S. King Drive has been vacant for nearly two decades and news reports say that The Obsidian Collection is ready to buy the home and turn it into a museum, library and archive for Black journalists and content creators.

Founded in 2017, The Obsidian Collection digitally archives photographs, video and documents to make Black history publicly accessible. The nonprofit got its start by organizing images from the Chicago Defender’s archives, executive director Angela Ford said.

This is ironic because at the time of Mr. Palmer’s death, there was an unresolved lawsuit he had filed against the publication for slander. Additionally, one of the Obsidian board members is Chuck Bowen who publicly admits to often being on the opposite side of Mr. Palmer.

Lu Palmer was born in Newport News, Va., where his father was a prominent educator. He received a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Virginia Union University in Richmond, Va., and a master’s in journalism from Syracuse University in Syracuse, N.Y. Mr. Palmer died Sept. 12, 2004, at the age of 82.