While discussing Islam and activism over dinner in Philadelphia with a local longtime activist and scholar, this writer was told many “persons of the book,” whether of the Jewish faith, Christians or followers of the tenets of Islam, see faith “as a matter of one’s personal upliftment, rather than the upliftment of the people.”

Dr. Tony Monteiro is a former professor of African American Studies at Temple University and the creator of a Saturday Free School that focuses on the activist principles inherent in the work of such notables as W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King and the Hon.

Elijah Muhammad. He told me religion has two sides: “The prophetic which is the side that advocates for justice and even revolution, and the religious side that is just personal, where there is no prophetic element.”

He called the religious side the “opiate of the people, where people are encouraged to turn their backs on the world and focus on the world (afterlife) they hope to achieve.” On the other side of such a myopic or personal view concerning faith “is a side that’s activist and what we call prophetic,” he continued.

“This is where one attempts to base his or her life upon service to the people. And to the extent that one believes in a God, and one believes that man is made for God, the question becomes, is the God you believe in a God of Justice?”

Islam’s holy text, the Qur’an, encourages the faithful to “Be strict observers of justice, bearers of true evidence for the sake of Allah, even though it be against yourselves or (against your) parents or near of kin. … ”

During the 23 years that the Qur’an was revealed to Prophet Muhammad, Peace Be Upon Him, he united the tribes of Arabia, raised the status of women, restored social justice, and purified the land of false idol worship. To say that Islam’s personal or individual uplift is not directly tied to serving the wider community, with as the Qur’an encourages “their property and their persons,” is to be remiss in one’s duty.

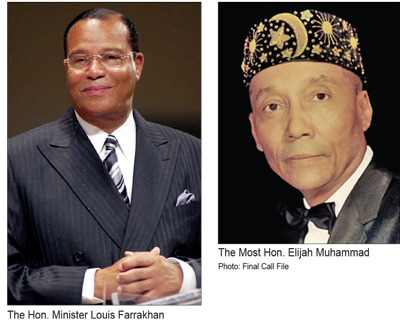

During the upcoming holy month of Ramadan where the 1.5 billion adherents will recommit to the principles of their faith, Islam is coupled with community involvement. The Muslim leader that most personifies activism, Dr. Monteiro explained, is Million Man March organizer and Nation of Islam Minister Louis Farrakhan, who expanded the principles included in the March during his tour of Africa. One of the reasons, Dr. Monteiro said, “many conservative Muslims have such a problem with Minister Farrakhan is his activism.”

In fact, according to Gayraud S. Wilmore’s 1973 book “Black Religion And Black Radicalism,” Malcolm X, a mentor of Min. Farrakhan, “brought black religion and black politics together for the spiritual edification and political empowerment of Black people.”

Gayraud argued that the “radical faiths” of Malcolm X, a student of and spokesman for Nation of Islam patriarch Elijah Muhammad, and Dr. Martin Luther King produced activism that “is neither Protestant nor Catholic, Christian or Islamic in its essence, but both comprehends and transcends these ways of believing in God by experiencing his real presence, by becoming one with him in suffering, in struggle and in the celebration of the liberation of man.”

Monteiro says Islam in the U.S. has a comfortable professional class of mostly immigrant Muslims, who don’t want necessarily to rock the boat, and as a result may be “conspiring to undermine the potentiality of Muslim youth,” he said.

Monteiro further discussed Islam and activism in the context of the Western Hemisphere-based African Diaspora. “Islam plays a role because Islam is viewed, first as non-European and it does not uphold racial categories. In fact, it tries to separate itself from it.”

Few are aware that a Muslim, Duse Muhammad, influenced Black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey and a former slave, a Jamaican Muslim named Dutty Bookman, influenced the Haitian revolution. Islam’s influence in the Western Hemisphere often played a big role because historically the Christian church was tied to colonialism and racism. “So Islam was part of that self liberation from all of the negativity that was a part of Western Christianity,” Dr. Monteiro said.

Black radical traditions inherent in the propagation of the faith by African Muslims and Muslims of African descent has a long history.

Cheikh Anta Babou, who has a PhD. in African history specializing in Islam in Africa and who grew up in Senegal, West Africa, argues, “As it relates to (the advent of) Islam, there has been a long process of what I call incubation, or what you might say a long conversation that (has) last(ed) for centuries between Islam and African traditional religions.” “So what resulted is the consequence of a very long conversation rather than the imposition of a dominant political and military power,” he said.

An associate professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Dr. Babou used an analogy to show acceptance of Islam helped enhance rather than turn Believers away from African traditional and cultural beliefs. He told this writer over coffee, “African traditional religion is the canvas on which (was put) all monotheistic religions.”

Various iterations and displays of faith practiced by Black Muslim adherents left Africa and traveled to the New World during the slave trade.

As outlined in Joao Jose Reis’ 1993 book “Slave Rebellion In Brazil,” one could witness in Bahia the historic and very public Eid al-Fitr festival signaling the end of Ramadan by free and enslaved Africans. He wrote about the building of a mosque, in secret, and the propagation of Islam through teaching the illiterate to read.

“In a society where even the dominant whites were largely illiterate, it was hard to accept (that) African slaves possessed such sophisticated means of communication. However, these papers revealed that among their slaves were people highly instructed in the language of the Koran (Qur’an), people who left their marks in perfect calligraphy and correct grammar,” Mr. Reis wrote.

Bahia’s Black Muslims, he wrote, became a “well-defined segment of the Bahian Black community; they had a charged identity and provided a strong point of reference for Africans living there. Slaves and freedmen flocked to Islam in search of spiritual comfort and hope … the Koran’s text was especially appealing because of sympathy for the discriminated, the exiled, the persecuted, and the enslaved.”

Prophet Muhammad’s companion, the former slave Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi, adds an historical connection to the activism inherent in Black Muslims’ response to oppression.

Long after the death of the Prophet, a group of nobles showed offense that a group of former Black slaves, including Bilal, were given an audience with Umar ibn al-Khattab, Islam’s second caliph, before them. Caliph Umar reprimanded them, saying, “By Allah, the virtue and excellence they have attained through the sacrifices they made in the way of Islam before you far outweigh the honor and virtue you now speak of. They surpass you in virtue and theirs is a degree you can never attain.”

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.