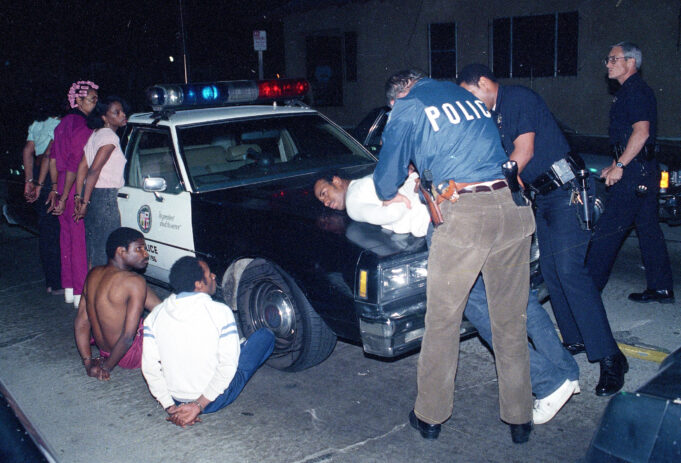

Aspiring lawyers Lawrence and Lamont Garrison, identical twin brothers, graduated from Howard University in May 1998. But a month before their graduation, they were arrested, and later sentenced for conspiracy to distribute crack cocaine.

“It was terrible because they had no drugs, no guns or anything like that. My sons went to school every day. They were going to Howard University. They graduated from Howard University in May, started court and by the time September rolled in, they were convicted,” their mother, Karen Garrison, also known as MommieActivist, told The Final Call.

“It was a horrible thing because they had never been in trouble before. Went to school every day, lived at home with me, never gave me an ounce of trouble. But because of mandatory minimums and sentencing guidelines that were set into place, the judge had no discretion. The prosecutors did whatever they wanted to do, and all they wanted were convictions, especially for Black people.”

Under conspiracy laws and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, they were convicted. Lamont Garrison told The Final Call that the conviction was based on the false testimony of an informant and that they were not actually found possessing cocaine. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act meant that people possessing five grams of crack cocaine were sentenced to at least five years in prison.

The law also caused crack cocaine related crimes to be punished at a 100 to one ratio to powder cocaine. A person who sold 500 grams of powder cocaine could get the same minimum five-year sentence as someone who sold only five grams of crack cocaine.

Under the 100 to one disparity, Jason Hernandez, a Latino, was sentenced to life without parole in 1998. “The person who provided me with the powder cocaine who was higher up on the, I guess you could say, on the distribution scale or on the totem pole, received 12 years. So because he had powder cocaine, he received 12 years, but because I converted it into crack, I received life plus 320 years. So that is like just a clear example, illustration of how huge that disparity is,” Mr. Hernandez told The Final Call.

Those laws caused over 3.4 million Black people in America to be arrested for cocaine offenses between 1980 and 2000, according to an in-depth report by Asbury Park Press. Both the remnants and the effects of those laws still exist today. With the passing of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 and the First Step Act of 2018,

The sentencing disparity decreased to 18 to one, over 2,000 people got their sentences reduced and about 3,000 people were released from federal prisons, according to a December 2019 report by Kara Gotsch of The Sentencing Project. But while the disparity decreased, many question why it existed in the first place and why it still exists.

“The disparity is not as great as the 100 to one disparity, but it still exists, and there was no pharmacological reason for the disparity in the first place, so there’s still no pharmacological reason for the disparity now,” attorney Nkechi Taifa told The Final Call. “Crack and powder cocaine, they’re both dangerous.

One is not more dangerous than the other. The only distinction between crack and powder cocaine is the manner of its administration, whether it’s smoked or whether it’s snorted. The only difference is a frying pan and some baking soda. You can turn powder cocaine into crack cocaine bam, just like that.”

Experts said crack cocaine is a cheaper option than powder cocaine, which makes it more accessible to Black and Latino communities. They don’t use crack more than Whites but are the majority of people locked up for low level drug selling.

“They are not drug kingpins by any stretch of the imagination, which really brings into question, why is the federal government spending any resources, quite frankly, and prosecuting cases, drug cases and dealing with people who are doing street level crime?” questioned Kara Gotsch, deputy director of The Sentencing Project.

“The lowest level people who are in the trade get the same sentence as the highest level. And because of the mandatory minimum sentences, the only way you can get out from under such a sentence is if you snitch, or what they call provide valuable information to the prosecutor,” Ms. Taifa said. “Many times, the low level people don’t have that information. That’s kept from them. They don’t have the information to be able to trade for their freedom, so they are the ones who are sitting in prison.”

In fiscal year 2019, there were 1,573 offenses involving crack cocaine, accounting for 7.8 percent of all drug cases, according to the United States Sentencing Commission. Of those offenses, 1,273 crack cocaine trafficking offenders were Black, 200 were Hispanic and 83 were White. Most of them were sentenced to prison, and the average sentence served was six and a half years.

On top of offenses in recent years, there are still people languishing in prison for possession of crack cocaine pre-2010, and Mr. Hernandez said there could be tens of millions of Black and Brown people who are shut out of society with as many rights as a slave because of their convictions.

“How is it impacting our community now? You have millions and millions of Black and Brown people in centralized areas that have felony convictions that can’t get a job, that can’t get public housing,” he said.

Crack cocaine is still negatively affecting Black and Brown communities not because of the actual drug being consumed, but because of the devastation that policies have on families, he continued. “It’s not the drug. It was these harsh, ‘say no to drugs’ or ‘get tough on crime’ policies that passed in the 1980s that hurt our community, destroyed our communities way more than they helped them out,” Mr. Hernandez said.

On January 27, 2021, Senators Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) introduced the EQUAL Act, which, if passed, would end the disparity.

But those in the fight to end it say that’s still not enough.

Ms. Taifa said there should be the total eradication of mandatory minimum sentences. Ms. Garrison said the majority of people making the laws are not the ones being impacted.

“If it passes, good. It’s still going to affect only a certain amount of people or certain types of people. They keep saying, you know, equality. What is that for a Black person? What is it?” Ms. Garrison asked.

Her son Lawrence, who passed away due to Covid-19 on Jan. 8, was released from prison in 2009, and her son Lamont was released in 2012. Now a Muslim, during his last five years, Lamont Garrison served as the study group coordinator for the Nation of Islam in the institution he was in.

“That definitely helped me reintegrate into society. I mean that was a huge help,” he said. “Having the teachings and trying to follow the Teachings of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad really helped me so much.”

He called the Fair Sentencing Act a “band aid on a gaping wound,” and said reconstruction of laws needs to go back to President Richard Nixon. Under Mr. Nixon’s administration, minimum mandatory penalties for drug offenses were signed into law. In 1994, John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s domestic policy adviser, told journalist Dan Baum that the drug laws under President Nixon were actually designed to criminalize Black people.

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities,”

Mr. Ehrlichman said, according to news report. “We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

“Go back to the statute, reconstruct it from there,” Lamont Garrison said. “Then you wouldn’t have these disparities, these racially effective, effective for them, disparities. Because it’s still affecting us.”

Today, Congress is still meeting over what to do about drugs. The House held a March 11 hearing on “Controlled Substances: Federal Policies and Law Enforcement,” where witnesses addressed topics such as federal drug policy and decriminalization. Mr. Hernandez, however, said the war on drugs is working how it was designed to work.

“It’s well-documented that the CIA through the Contra scandal was actually helping and allowing drugs, cocaine and crack cocaine, to just run wild in our communities and not do nothing about it. So, I mean here we have something that’s government created, and then the government comes around and punishes Black and Brown communities that were being ripped and devastated by crack cocaine at that time. Instead of, you know, investing in our communities, instead of investing in drug treatment and helping for the infrastructure in our communities, like parks or afterschool activities,” he said.

He said the war on drugs was never designed to stop drug use, stop drug selling or make communities better. “The war on drugs was probably the greatest program or initiative or legislation that the government, the most successful that they ever passed because it did exactly what they wanted it to do: mass incarceration of Black and Brown people,” he said.

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam talked in-depth about the crack cocaine conspiracy in a 1996 lecture titled “Crack Cocaine—The Great Conspiracy to Destroy The Black Male.”

“Crack cocaine is from the government of the United States of America. And when I have said this, some of you thought I was paranoid. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, I went across this country asking you to stop killing yourself (‘Stop The Killing’ tour), because I knew that the government was making war on Black youth, Black men in particular,” he said.

He urged young people to escape the conspiracy that many may find themselves trapped in.

“You may say ‘I make my living selling drugs’—yes, but you can sell something else. See all the money that you get selling drugs? It comes easy, and it goes easier. And when the enemy gets ready for you, they bust you and take everything and put you in prison,” he said.

“We have to get away from being a victim in a conspiracy, and begin to take the offensive and carry the fight for freedom and justice to the enemy rather than always being on the end of their traps complaining about what White people are doing. We have to find that friend that will strengthen us against the force of evil and make us victorious.”