White rage is a religion.

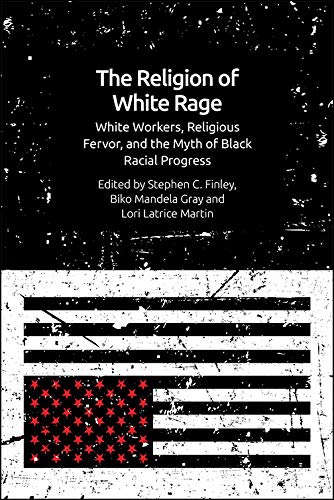

At least, that’s what several writers and scholars argue in the book, “The Religion of White Rage: Religious Fervor, White Workers and the Myth of Black Racial Progress,” co-edited by Stephen C. Finley, Biko Mandela Gray and Lori Latrice Martin.

The co-editors explained the concepts of the book on a series hosted by Louisiana State University’s Reilly Center for Media and Public Affairs, called “Racism: Dismantling the System.”

“2016, Trump became president. And some things changed, some things stayed the same. But the way militias and White nationalists and White supremacists seem to flourish in that context, we thought that it was worth some theorizing to bring a group of scholars together and edit several essays that helped to make sense of Whiteness in this moment,” Dr. Finley, an associate professor of religious studies and African-American studies at Louisiana State University, told The Final Call.

He said he and the contributors wanted to talk about how only White rage is legitimized in American culture. “White rage is this sense of the righteous indignation,” he said. “It implies something morally right, a posture or position of moral rightness, and for us, that was a religious disposition. This idea that the primary lens through which they engage the world is Whiteness is why we want to call that religious. In other words, that Whiteness interfaces with the world, it organizes the world, it’s the lens through which they view the world, it gives them their perspective.”

White rage, Dr. Finley said, is a response to Black racial progress.

“And I think the fruit of it can be seen in the Capitol siege of Jan. 6. I mean, that was White rage at its finest, on display for everybody to see. But that rage does not exist separate and distinct from anti-Blackness. It’s fueled and motivated, even when unacknowledged by anti-Blackness and by this perception that Black people are progressing politically and socially and economically in America, whether it’s real or not,” he said.

“Again, it’s the perception. And so that’s the first point or the first two points. And that in addition to being motivated by this perception, it’s also animated by the sense of loss. One, that White people will lose their position in the world, and then two, that Black people would gain position in the world; significant position and power in the world.”

In the panel discussion, Dr. Biko Mandela Gray, assistant professor of American religion at Syracuse University, said they had no clue the Jan. 6 insurrection would happen. The book was published on Sept. 15, 2020, about four months before the events at the Capitol.

Kate Temoney, an assistant professor of religion at Montclair State University and the co-chair of the Religion, Holocaust, and Genocide Unit of the American Academy of Religion, wrote a chapter in the book titled, “Analyzing white rage: Race is my religion and white genocide.” She told The Final Call that those two phrases together, “race is my religion” and “White genocide,” unify people.

“You no longer have to worry about people’s religious affiliations or a difference that they might have in religion, or whether or not they’re religious in order for you to join us in claiming this kind of identity as being White. So that’s what I think race is my religion does,” she said. “And I think the White genocide part unifies because it then brings people together in order to try to respond to an existential threat. So the idea that we’re under siege; we’re a besieged group and that we need to somehow unify and understand that in order to be able to react.”

She said White people have latched onto the legal term of genocide to lend legitimacy to their grievance.

“They’re claiming that there is a Jewish conspiracy, then, to eliminate them and that they have to fight back, that they have to somehow preserve the White race in the face of what they see as an assault on White people,” she said. “And one of the ways in which they point to evidence of this is the fact that the White population is declining, which is a fact. We’ve known for quite some time, what we call the browning of the United States or the fact that the world over, there are more people of color than not.”

Dr. George Yancy, a professor of philosophy at Emory University and author of several books on racism and Whiteness, also told The Final Call that White rage operates under the assumption that any progress for Black people and people of color means the diminishment of White people.

“Any form of White rage that takes the form of a certain kind of White nationalism I think is unethical. So the storming of the Capitol, for example, for me would be profoundly unethical and anti-democratic and in fact anti-Black,” he said. “Whereas, when we think about Black rage, I think what we’ve got is clearly a case of righteous indignation, given the history of Blacks in this country in the way they’ve been treated let’s say for 400 years under legalized slavery and then under de facto forms of racial oppression.”

He explained Whiteness from a historical context, starting with European philosophers such as Immanuel Kant, David Hume and Hegel, all of whom held racist views towards Black people. “I think of Thomas Jefferson for crying out loud, who argued that Black people don’t have any creativity.

Even our best poets, for him, are only capable of producing inferior work to Whites. You have people like Johann Blumenbach, who argued that Adam and Eve were White. So, at the very beginning, you have this idea that White people are at the very apex of civilization. Carl von Linnaeus who held that Black people by their very nature are lazy people. And you just go on and on,” he said.

“I think that what this raises is the historical question of who it is that possesses the concept of the anthropos. In other words, who is it that gets to control who is human and who isn’t, and it’s clear to me that in Western European countries, for them under their White racist views, they held that Whites are fundamentally human whereas Blacks are not. That’s just the bottom line,” he continued.

“And so when you’re thinking about racism in America and you’re thinking about the emergence of Whiteness, you’re really thinking about the emergence of a moment in human history where White people are defining themselves in relationship to people that they are not, so that we become the enemy, we become the inferiors, we become the hypersexual, we become the uncivilized savages, whereas White people become the exemplars of civilization, exemplars of reason and law; whereas we are individuals who are in disarray and therefore it’s the White European’s job or the Anglo-American’s job to civilize us.”

He argued that Whiteness is about the control of Black bodies, from the Black codes after slavery up until today. “You think about Eric Garner, who cried out ‘I can’t breathe’ 11 times, but no one, apparently, heard him say this. In some sense, when Black bodies cry out, they can’t even be heard. They’re not even hearable, in some sense. Take George Floyd, who was killed right before us,” he said.

“The whole world got to see. How is it that you keep your knee on someone’s neck for that amount of time without at some level that person’s humanity speaking back to you in a resistant way? Well, it didn’t speak back to, in this case, officer Chauvin. It just didn’t. Or think about Breonna Taylor. Think about Ahmaud Aubrey. Think about Trayvon Martin.

These cases are updated versions of the Fugitive Slave Law. George Zimmerman, the killer who went after Trayvon Martin, took it upon himself to function as a police officer, took it upon himself to act in the name of Whiteness to keep that community safe and safe from who? Safe from the non-human. Safe from the sub-person. Safe from the criminal.”

Dr. Yancy penned an article in the New York Times titled, “Dear White America,” in 2015. He received backlash. The writers and editors of “The Religion of White Rage: Religious Fervor, White Workers and the Myth of Black Racial Progress” have also received backlash.

“Some of the response to the book has been White rage. Isn’t that ironic? We’re writing about White rage and how it erupts, and then the response to the book has been White rage,” said the book’s co-editor Dr. Finley. He said White rage will never really go away because it’s neither Republican or Democrat; it’s American.

“We’ll continue to see certain policies that harm Black people, that consolidate whiteness and White power, only it won’t come with racial epithets and overt anti-Blackness,” he said. “It will come like the tough on crime bills did in the ’90s that Bill Clinton supported and that Biden helped write that incarcerate Black people inordinately.”

Dr. Temoney brought up how both the religion of Christianity and White privilege was on display during the insurrection, and she said people will continue to see resurgences of White nationalist groups. She cited a metaphor made by Isabel Wilkerson about an old house in disrepair.

“The United States is kind of built on a foundation that’s rotten. We seized land from native peoples. We built an economy that was on enslaved labor. And so we have a history that we have yet to reckon with, and we see this erupting all the time, that we’re still a country divided that hasn’t dealt with its past,” she said.

“And so this house that we all have now inherited, because this house was built several hundreds of years ago, but we’ve inherited that house, and we’ve inherited the history of that house. And so one thing that she says is that it is not on people of color, African-Americans, Black people to fix this. I guess I’ll say it’s not so much what we should be doing, but what we shouldn’t be doing,” she continued. “This is something that needs to be fixed by the people who put it in place.”

Dr. Yancy said that even with the browning of America by 2050, Whiteness will still operate as a power and that the United States could become structurally like South Africa, where the majority of people are Black but the few White people there are in positions of power. He described the way he feels as “hopefulness that is saturated with pessimism.”

He said Black people need to continue to protest, whether that looks nonviolently or it looks like war. “While I’m not advocating for a war, I’m saying that there’s a time when a people, they have to rise up and do more than they’re doing, especially if marching just means more increments, more piecemeal stuff, a little more a part of the pie but never a part of the pie that is significant,” he said.

He said Black love is necessary and that Black people should hit White people in their pockets. “I think that Black love is central to that resistance to White supremacy and Whiteness. And I also think that hitting them economically in terms of our solidarity is another place of hitting them. But at the same time, I argue that I think we have a right to self-protection,” he said.

“When White people kill us willy nilly, I think we have a right as a people to stand up to defend ourselves. And if that looks like armed struggle, although I’m not advocating for it, then it wouldn’t be unusual. It wouldn’t be the sort of thing that White people should say, ‘Oh, you guys are horrible because you’re engaging in armed struggle’ because White people have always engaged in armed struggle when it’s about their preservation. But somehow we are not supposed to do that. Well, that’s not true. It shouldn’t be true. How’s that?”