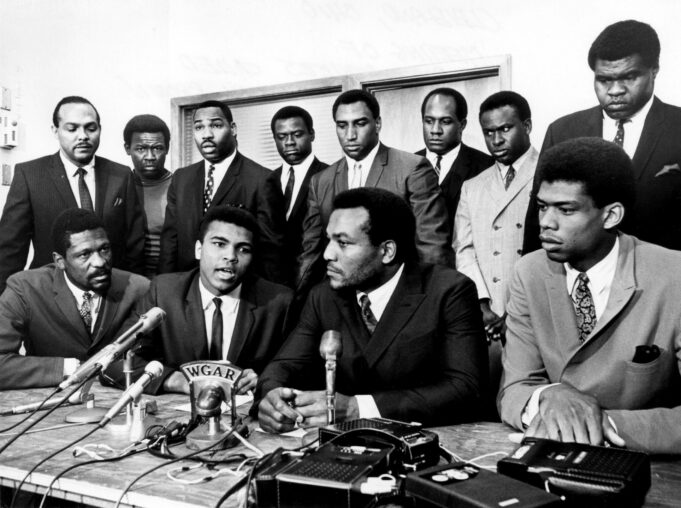

Football legend and actor Jim Brown in 2016, was in Cleveland, discussing what was called in 1967 “The Cleveland Summit,” others called it the “Muhammad Ali Summit.” The historic gathering included sports greats Lew Alcindor later to become Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Bill Russell. “We couldn’t of gotten those guys together for anyone except Muhammad (Ali),” said Brown during his 2016 remarks.

“They all loved him and admired him and his sense of humor. For him to be younger than most of us—Kareem (then playing at UCLA) was the youngest—for him to be younger than us and to have that kind of courage was just amazing.”

The event was the first of its kind. Black professional athletes had never banded together to use their platform to express their discontent about a specific issue—Ali’s anti-Vietnam war stand and his conscientious objector position. “The summit,” according to undefeated.com, “was a catalyst that signaled the importance of unity and triggered a chain reaction of similar protests.”

At the day of the event, reported the Cleveland Plain Dealer, hundreds of “Clevelanders crowded outside the offices of the Negro Industrial Economic Union or NIEU … None of those gathered, including a collection of the top black athletes of that time, realized the significance of what would happen in that building on this day.” NIEU was a Black economic empowerment organization later named Black Economic Union founded by Jim Brown.

Ali, referred to by many publications as the “most polarizing figure in the country” was inside Jim Brown’s office being grilled by the likes of Bill Russell, Lew Alcindor, Walter Beach of the Cleveland Browns and Willie Davis of the Green Bay Packers. They weren’t looking for him to comment on his position on sports labor issues.

“They wanted to know just how strong Ali stood behind his convictions as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. The questions flew fast and furious. Ali’s answers would determine whether Brown and the other athletes would throw their support behind the heavyweight champion, who would have his title stripped from him later in the month for his refusal to enter the military,” reported the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

The meeting was a watershed moment in both the civil rights movement and the protest movement against the war in Vietnam. A convergence of social and cultural forces intersected, including issues on race, religion, politics, economics, civil rights, and the anti-war movement.

Ali, according to Cleveland’s 3News Senior Commentator Leon Bibes, spoke on his religion and Black pride never wavering from his conscientious objector stance.

“It was the Ali Summit eventually called the Cleveland Summit,” according to Bibes. The building where they met is gone now, but Bibes went on to say, “The meeting was historic in every sense of the word. Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown and the others marked a turning point in the civil rights movement. The issues all converged right here in Cleveland. Race, politics, sports, religion and the war in Vietnam. Nineteen sixty-seven marked a turning point for the nation and for Black political and social power.”

To put an exclamation point on this meeting, Ohio State Rep. Carl Stokes, who attended the summit, later that year would become Cleveland’s first Black mayor, and one of the first African Americans to lead a major American city.

Reflecting years later on the summit, Willie Davis said, “When I look at the situation in Florida (the Trayvon Martin case) and when I look through all my adult life, there’s always been a period where something happens that causes this country to struggle, be it racial or whatever.” He continued, “I look back and see that Ali Summit as one of those events. I’m very proud that I participated.”

The individual responsible for assembling the group was John B. Wooten, a former teammate of Brown who served as the executive director of NIEUs Cleveland office. The organization was founded by Brown in 1966 with the purpose of creating “an economic base for the African-American community” said Wooten. After being instructed by Brown to put together a group of athletes that would hear Ali out before a planned news conference, Wooten went to socially conscious athletes who had supported the NIEU,” wrote C. Isaiah Smalls in theundefeated.com.

Smalls writes that Walter Beach was “an integral part of the dawn of Black athletic activism in 1967.”

According to Beach: Not many players would be willing to “jeopardize their livelihood.” Russell, Alcindor, Bobby Mitchell, Sid Williams, Curtis McClinton, Willie Davis, Jim Shorter and even Wooten himself were all still playing professionally when they decided to offer their support. Even Brown, who partnered with the company that promoted Muhammad Ali’s fights, stood to lose a lot of money if Ali followed through on his conscientious objector position, Beach said. He said they all recognized the issue was bigger than themselves and their careers.

Beach was once cut from the Patriots in 1963 and labeled a “troublemaker” for organizing a protest among Black players against segregated living conditions during the teams road trip to New Orleans. He cited a variety of emotions, including shame and anxiety, that ultimately prevent many Black athletes from speaking out against racial injustice. Although he retired a year before the summit, he said football was never more important than his personal sovereignty.

He recalled a story in which Art Modell, former owner of the Browns, told him that he could not read the book “Message To The Black Man,” by the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. Beach balked.

“You own this football team, but you don’t own me!”

The summit for Alcindor was a turning point. This demonstration of Black power and solidarity marked for him the first time African American athletes got together across various sports to rally behind a single cause. The gathering inspired Alcindor to see himself in the same light as Ali, Brown and Russell, reported The Undefeated. The basketball great realized he had the responsibility to use his platform, whatever the cost, to speak out against racism and injustice. In his book “Becoming Kareem: Growing Up On and Off the Court,” published years later, he wrote.

“Being at the summit and hearing Ali’s articulate defense of his moral beliefs and his willingness to suffer for them reinvigorated my own commitment to become even more politically involved.”

Ali’s first anti-Vietnam war remark, according to his autobiography, “We ain’t got nothing against no Viet Cong,” occurred in Miami, in front of a group of children. It was repeated in front of reporters. From that moment until he stood before the draft board, Ali was constantly pressured to recant his stance.

One thing that gave him strength and helped him hold his position was a meeting with Elijah Muhammad, where he told Ali, “Brother, if you felt what you said was wrong, then you should be a man and apologize for it. And likewise, if you felt what you said was right then be a man and stand up for it.”

In the online video “United We Stand: The Muhammad Ali Summit,” defending his position on the Vietnam war Ali told a talk show host, “I believe in the Holy Qur’an which says we who declare ourselves to be righteous Muslims don’t take part in no wars in no fashion and form which take the lives of humans unless it’s a holy war declared by God Himself. And I think anyone if he knew it was God calling, he’d fight for God.”

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter