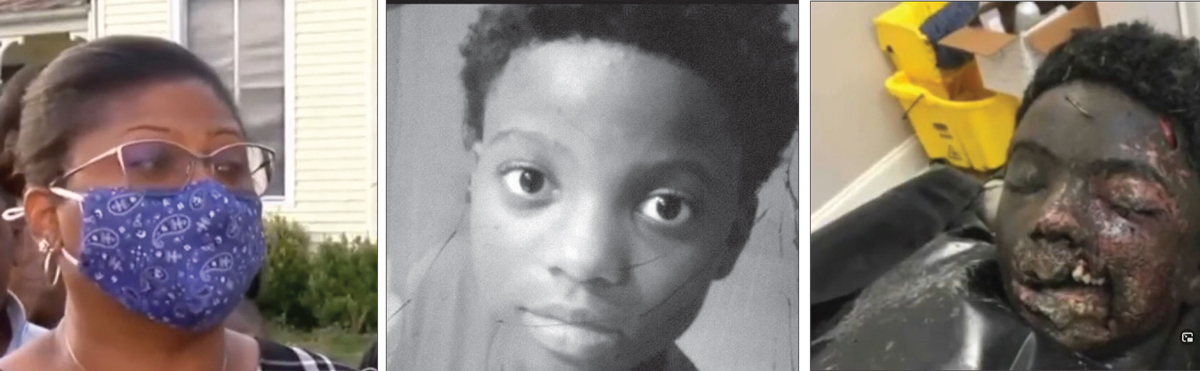

The body of Quawan “Bobby” Charles, 15, was found cold, facially decomposed, and face down in ankle deep muddy water in a sugarcane field 25 miles from his father’s home.

It was a parent’s worst nightmare. Questions concerning his cause of death and the police response to his parents’ Kenneth Jacko and Roxanne Nelson desperate pleas for help struck a chord.

One of the last people to see Quawan alive, Janet Irvin, was arrested and was charged with failure to report a missing child and contributing to the delinquency of a minor on Feb. 9.

October 30, 2020 was a particularly chilly day in Baldwin, La., where Quawan resided with his father. His parents notified police he was missing at 8 p.m. that evening.

Baldwin police responded to the parents’ report by alerting the local St. Mary Parish Sheriff’s Office and entering the information into a national database.

Quawan was found dead four days later.

According to longtime community activist Khadijah Rashad, if it had not been for the actions of family and relatives, there is no telling when his body would have been found. “On Nov. 2, the family learned that that Quawan had been at the home of a 17-year-old White friend and the friend’s mother later identified as Janet Irvin, who picked the youth up in their car from his father’s house,” she said. It appeared to be a break in the case.

What is puzzling, according to news sources, is that after police interviewed Ms. Irvin and her son, the mother admitted that Quawan was at her home. She reportedly told a private investigator for Quawan’s family that he allegedly smoked marijuana and drank alcohol while under her supervision. He also reportedly consumed psychedelic mushrooms, she said. The child’s parents had not approved of or knew that he was with her.

Ms. Irvin states Quawan fell asleep, awoke agitated, threatened suicide, and left her home. The police took no immediate action against her.

Ms. Rashad further told The Final Call it took Quawan’s mother, Ms. Nelson, to pressure the local Iberia Parish Sheriff’s Office, in the area where Ms. Irvin resided, to ping Quawan’s cell phone.

According to press reports, Baldwin’s Assistant Chief of Police Sam Wise said his department did not have the technology to do a ping.

Iberia Parish deputies were able to ping the phone and narrow the search to where Quawan’s body was found.

Quawan’s case hit all of the negative benchmarks for how the cases of missing Black children are mishandled, according to some advocates. Police initially were reluctant to take a missing person’s report— telling the parents he was most likely at a local football game that night—and losing valuable time, according to Devon Norman, a community activist with the organization The Village. There was no Amber Alert nor any quick press or media coverage.

The case also takes bizarre turns. According to an autopsy report, he was seen crawling naked through drainage pipes. But no reports were made to authorities. He was unclothed when found. According to the Weather Service, the temperature was in the low 60s to upper 50s. The autopsy says reportedly after smoking a substance, Quawan passed out, and when he awoke, he became combative. The autopsy’s primary finding is evidence of drowning, according to the Louisiana Forensic Center. The report found muddy water in the airways from the mouth and nose. There was no mention of his clothing being found.

The toxicology test was positive for THC from marijuana and alcohol. Expanded testing for synthetic cannabinoids and hallucinogenic mushrooms was negative. After death markings were consistent with injuries from animals and, or insects, the autopsy report states.

In a Feb. 5 press release responding to the autopsy findings, Ron Haley, an attorney for the Charles family, said, “A complete autopsy examination and report on the death of Quawan ‘Bobby’ Charles have been completed by forensic pathologists at the Louisiana Forensic Center. Though the report declines to name with certainty the method of drowning, a simple process of elimination leads to only one reasonable conclusion: homicide.

“It is well-understood that the accidental drowning by an able-bodied person in ankle-deep water is nearly impossible. Additionally, while the report notes that suicide by drowning is rare, it also indicates that a struggle as part of a homicide could not be ruled out here. Conveniently, those ‘witnesses’ claiming that sweet, kind, and healthy Quawan was suddenly combative and threatening to kill himself are presumably the very people looking to protect themselves—Janet Irvin and her son.

“The only rational, glaringly obvious conclusion is that there was foul play at work here, and there has long been enough evidence to arrest Janet Irvin for her involvement in the tragic death of Quawan Charles.”

Louisiana is one of 25 states that has a Drug Induced Homicide law. It applies when “the offender unlawfully distributes or dispenses a controlled dangerous substance listed in Schedules I through V of the Uniform Controlled Dangerous Substances Law, or any combination thereof, which is the direct cause of the death of the recipient who ingested or consumed the controlled dangerous substance.” A conviction results in a second-degree murder charge.

Following the arrest of Ms. Irvin, Sheriff Thomas S. Romero of Iberia Parish said in a Facebook message, “I hope this arrest begins to help their family heal … . And by no means is this case closed.”

Community activist Khadijah Rashad attributed the arrest to community pressure. She told The Final Call, “Finally there is an arrest, and it is the result of the pressure and protests and everything. Without the protests, Ms. Irvin could have gotten away with it. You must remember, however, an arrest don’t actually mean too much if you are White in the state of Louisiana.”

Mr. Norman, the community activist, was pleased to see the arrest. But he called the minor charges a slap in the face. “The charges are ridiculous,” he said. “I think that Quawan was lynched, and I think that the local government, policing agencies understand how serious this issue is. And that it is far beyond child neglect or failure to report a missing child or contributing to the delinquency of a minor.”

“I’m grateful you know that something has been done, but I don’t want to be complacent. And I don’t feel like we have victory because this is not a victory, you know, it’s unfortunate still, and we got a lot of work to do,” Mr. Norman concluded.

“What we want is justice, unrestricted and unfettered justice, not the sort of justice that slow rolls the death of a teenage child,” Jamal Taylor with organization Stand Black told The Final Call.

Family spokesperson Celina Charles, in a text to The Final Call, said even with the arrest of Ms. Irvin, the finish line was not close. “There is still more work to do. We want to see everyone that played a role in Quawan’s murder arrested and convicted,” she said.

The FBI’s National Crime Information Center database listed 424,066 missing children under 18 in 2018, the most recent year for which data was available.

According to CNN, about 37 percent of those children are Black, though Black children only make up about 14 percent of all U.S. children.

A 2010 study found missing Black children were significantly underrepresented in TV news reports. Though over a third of all missing children in the FBI’s database were Black, they only made up about 20 percent of the missing children cases covered in news media.

A 2015 study was bleaker: Black children accounted for about 35 percent of missing children cases in the FBI’s database and were only seven percent of missing children cases in media references.

Experts say media coverage is vital to helping solve these cases. Law enforcement often classifies children of color as runaways without having all the details. Because these children are considered to have voluntarily left home, Amber Alerts aren’t sent out and they aren’t typically covered in news reports.