Activists are in urgent fight for release of aging political prisoners held captive inside the U.S.

The United States’ denial of Black and Brown political prisoners oozes a greasy history of hypocrisy and lies.

And as social justice movements begin to gain momentum and talk of dealing with mass incarceration and defunding or radically reforming police grows, they are a reminder of how prisons are used as a tool for social control and a warehouse for socially oppressed people.

Political imprisonment and political prosecutions have a long and deep history: Huey P. Newton, Black Panther Party co-founder and leader, was accused in 1968 in Oakland of first-degree murder, felonious assault, and kidnapping connected with the death of one police officer and the shooting and injury of another police officer. With a majority White jury, Mr. Newton was acquitted of assaulting an officer, and convicted of voluntary manslaughter. His conviction was reversed by the California Court of Appeals. Two more unsuccessful trials followed before all charges were dismissed in December 1970.

Black power activist Angela Davis was charged and acquitted on charges of conspiracy, murder and kidnapping by a jury in San Jose, California in 1972.

Ramona Africa, of MOVE, a Philadelphia- based Black liberation organization, lived through the 1985 police bombing of MOVE headquarters. “Eleven people had died in the MOVE house from the resulting fire, 6 adults and five children, and 250 neighborhood residents left homeless from the incident,” according to the Amistad Research Center. She was imprisoned for seven years on riot charges, but a lawsuit led to her being awarded $500,000 “for pain, suffering, and injuries related to the 1985 incident,” said the center.

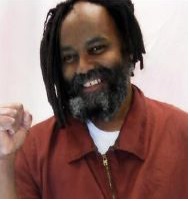

Mumia Abu-Jamal, a former Black Panther, MOVE member and community journalist, has served almost 40 years in prison for allegedly killing a Philadelphia police officer. Supporters say he is innocent and are awaiting a new trial with the discovery of evidence not given to the defense at his initial trial. His death sentence was overturned by a federal judge in 2001. He was given life without parole.

Longtime Native American political prisoner Leonard Peltier, who based on a June 26, 1975 shoot out and has been in captivity for over 30 years, was wrongfully convicted in the deaths of two FBI agents and targeted by FBI Counterintelligence operations against him and American Indian Movement leaders. He is serving two consecutive life terms.

Imam Jamil Al-Amin, formerly known as Black Panther leader and activist H. Rap Brown, was convicted for a murder that he did not commit in 2002, say supporters. They say his prosecution was politically motivated and he remains imprisoned despite someone else confessing to the killing of the police officer authorities say he is guilty of.

American political prisoners and their existence go to the core of a society’s racist nature. To dismiss the issue of political prisoners in the U.S. is to ignore America’s authentic character.

Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans and others have been jailed for their politics since the era of the 1960s and 1970s. They have languished in jails for years, labeled “common criminals” to hide the human rights violations that they have suffered.

While the true number of political prisoners in the United States is hard to quantify, there are about 100 political prisoners in various prisons throughout the United States, according to progressive organizations and groups such as the Jericho Movement, which is devoted to freeing Black political prisoners.

Many of these domestic prisoners of war go back to the heyday of the civil rights, Black Power, and New African Liberation struggles.

They also include members of the Puerto Rican independence movement, Indigenous peoples and the Chicano liberation movements and other political struggles.

Some are well known, others not so much. Most of these political prisoners today have been locked down since the 1970s and 1980s. Some were convicted on made up charges, others under vague political conspiracies or acts of resistance.

All received extensive sentences for their political beliefs or actions to demand freedom for oppressed people, say supporters.

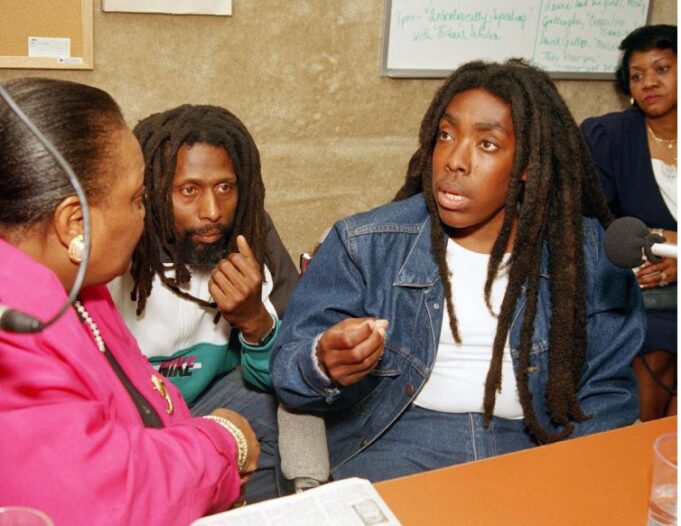

Active in the fight for justice is the Jericho Movement. In a detailed interview, its chairmen talked about how the organization had to pivot in terms of strategy as time is running out for many of these men and women.

“I would say the movement is still alive, and those freedom fighters that have come through the movements from the ’60s and ’70s, they’re getting older, and the situation in terms of strategy to get them out is changing,” said Jihad Abdulmumit, chairman of the Jericho Movement.

The strategy has moved away from a militant stance in advocating in their behalf to a more humanistic approach in appealing to parole boards.

“So what we do now is trying to focus on the violations and abuses of discretion of parole boards, and this is in essence how many prisoners have been getting out. We point out their exemplary prison records, participation in education programs, and help given to other inmates. We ask the question do they meet all their qualifications of parole? They served their time. We ask the question, if a judge gives you 25 years, why are you in prison for 50 years? Nothing is mentioned about being a political prisoner,” he said.

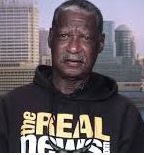

Eddie Conway, a former Black Panther who served a 44-year prison sentence, told The Final Call, time is running out. “It’s the government’s intention to let them die in the prison system. They’re treated unlike any other prisoners in terms of length of sentence and time served,” said Mr. Conway.

He vows to continue to advocate for his comrades and intends to highlight the case of Sundiata Acoli, a mathematician that has been incarcerated since 1974. He was granted parole only to see it overturned.

Mr. Conway also pointed out how those who come to political consciousness behind the walls are targeted for political beliefs. “These are people who became more politically aware and active once they landed in prison. Many of these prisoners also get singled out for extra harsh and restrictive treatment like the political prisoners,” he explained.

Pam Africa of the MOVE organization told The Final Call she remains optimistic. “We will continue to fight. Who would have thought the MOVE 9 would be released from prison? Who thought that Seth Hayes would be released from prison? I am very hopeful. People have to push and expose and that’s what we’re asking people to do now, to expose what is going on with Mumia now more than ever. And he has a chance to come out within a year based on prosecutorial misconduct in his case,” she said.

According to community activist Wazzer Hazziez, the case against Omar Askia Ali should be more widely known. He is a member of the Nation of Islam, a political prisoner wrongfully sentenced to life in prison 49 years ago, said Mr. Hazziez.

“Mr. Ali’s crime is he ran afoul of the police in his endeavor to rid the community of drugs,” Mr. Hazziez pointed out. “Unjust incarceration goes back. It goes back as far as Marcus Garvey, Fard Muhammad and Elijah Muhammad. So Mr. Ali is in good company. They (authorities) don’t call them political prisoners; it’s a game of suppression.”

“I think this is a time for us to have this discussion,” said Omali Yeshitela of the African People’s Socialist Party. “I do think it’s very difficult for the political prisoners. And I do think the movement has recovered and is able to raise these issues and questions and able to honor those brave men and women who put their lives and freedoms on the line for us.”

Mr. Abdulmumit said the Jericho Movement represents about 30 political prisoners.

“We are in communication with everybody; we help assist with their medical needs, help with legal fees and advocate parole boards on their behalf. It’s really hands on. It’s just not slapping your name up on a website and leaving it there,” he said.

Pam Africa said, “We got to keep on working. We must stay consistent. We got to bring the Black Lives Matter movement along and sit them down and talk with them and to have them understand whose backs they are standing on.”

For Eddie Conway an education initiative includes naming projects after political prisoners to keep their names in public. He also advocates having potential elected officials pass a litmus test on support for political prisoners before any elections.

Part of the problem, said Mr. Hazziez, is fear. “You have to cultivate leadership that is not afraid to speak out,” he said.

Mr. Abdulmumit, discussing the role of the international community in this struggle, talked about the United Nations Special Rapporteur’s non-position on Black political prisoners in the U.S. today.

“The International Commission of Jurists back in the 1970s came through and visited with Ed Poindexter and Sundiata Acoli and acknowledged that they were Black political prisoners. The United Nations is a little tough to deal with on that issue,” he said.

“I’ve represented the issue of the political prisoner at the Geneva Convention, at different treaties (discussions). It’s a hard sell. You sit there, and you talk about political prisons through the United Nations networks, and they look at you like looking at a deer in the headlights. I think to be very candid, the United Nations has been very lame, insipid and weak when it comes to issues that deal with Black people in the United States. Period.”

Ted Kelly of the Prisoners Solidarity Committee argues the definition of political prisoners should be broadened to include all Black and Brown people who are incarcerated.

“The fact of the matter is this is a White supremacist system. The justice system is White supremacist as well as the institutions of the country. So from that perspective, people of color in the U.S. penal system are political prisoners because the justice system is not designed for justice. It’s designed to kidnap Black and Brown people disproportionately from their communities and force them into free labor. They’re concentration camps for the poor and oppressed, they’re concentration camps for Black and Brown people,” he said.

Mr. Kelly said of paramount importance are health issues suffered by these “prisoners of war.” “Covid has accelerated everything now. Every day our soldiers and our political prisoners are stuck behind bars is another day that the state could steal them from us. Russell Maroon Shoatz has Stage Four cancer and covid, and he’s in his late 70s. This month was the one-year anniversary of Delbert Africa’s prison release. He was part of the MOVE 9. It was a major victory, but Delbert died like months after his release because these prisons are killing people.”