In these times that try the human soul, the important African proverb that “it takes a village to raise a child” takes on a whole new sense of urgency and a call to action in meeting the immense needs of Black youth and young adults. One way is providing and supporting meaningful, substantive mentoring programs as we observe National Mentoring Month in January.

According to the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, Black males 18 and older make up just a small percentage of all college students. “In 2008, Black males ages 18 and over represented only 5 percent of the total college population,” according to report by the foundation in collaboration with other agencies, titled “Challenge the Status Quo: Academic Success Among School-age African-American males.”

According to the ACLU, one out of every three Black boys born today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime. The challenges for Black female youth are also concerning.

“It’s not a secret that Black girls face quite a few disparities due to race and gender. Overall, Black girls have become overpoliced and underprotected and most certainly forgotten in several different movements and intervention plans,” writes Deja Jones in the article, “Why More Black Women Need to be Mentors.”

The Final Call interviewed Black mentors and the thread that tied their various programs together in addressing the myriad of obstacles our youth face. They agreed on the great need for Black children to have mentors that look like them as they inspire youth to grow, develop and fulfill their potential.

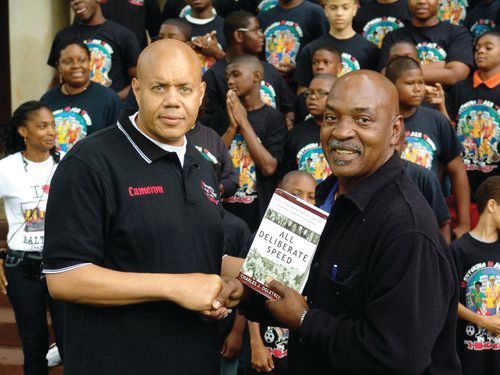

Cameron Miles is CEO of the Baltimore-based Mentoring Male Teens in the Hood in existence for 25 years. “We are the world’s greatest group-mentoring program where education, speakers, trips, sporting events, health forums, conflict resolution, STD and AIDS workshops, and real conversations about the ‘hood’ come together to build strong kings and prepare them to compete in a society that too often allows them to slip through the cracks,” he told The Final Call.

For him mentoring programs are extremely paramount. “Coming from the deadly streets of Baltimore where over 300 murders took place last year when you don’t have a mentoring program, our young men can get caught up in traps like drug dealing, robbery, car theft, human trafficking. So they need a place where they can come, where we can talk about the importance of a firm handshake, the importance of looking someone in the eye,” he said.

“How to say please and thank you, yes ma’am and no, sir. Learning about Black history, which is not taught in our school system, learning about Denmark Vesey, Frederick Douglass, Dr. King, Malcolm X, and Harriet Tubman there are just so many things,” he pointed out.

Groove Phi Groove Social Fellowship Inc., founded at Morgan State College as an alternative to mainstream Black Greek-lettered fraternities, is the largest non-Greek college-based organization in the country. According to their international president Ahmad McDougal their mentoring outreach effort is vitally important. It includes the identification of schools in neighborhoods that are threatened but viable. “We have taken Saturday detention and turned it into Saturday mentorship,” he said. The vehicle used by his organization is the Groove Leadership Academy.

Mentorship for Black females might be more critical. In a doctoral thesis entitled, “Critical Mentorship for Black Girls: An Autoethnography of Perseverance, Commitment, and Empowerment” by Krystal Huff, she writes, “Black girls continue to suffer from the longstanding ills that stem from institutional structures steeped in racism and capitalism. Moreover, oppressive institutional policies result in limited life outcomes for Black girls, including criminalization and increased involvement with social services such as the foster care system. The demonizing depictions of Black females as hypersexual, belligerent, and angry.”

Allegra Muhammad is author of the book, “Better Me and CEO of SWAP (Socializing with a Purpose),” a girl’s mentoring program based in Wilmington, Del. “In inspiring Black Girl Magic, I found those in my group benefited from exposure to new experiences like music, arts, and culture trips. You know many of them have never been outside of Wilmington. In my experience, I found that the mothers required mentorship as much as their children. So, you have to take on the whole family to see what the need may be.”

“Girls Like Me Project,” a Chicago-based mentoring program, provides its participants with media literacy training and digital storytelling training. The organizations goals includes helping girls understand the stigma and stereotypes directed at them that limit their self-worth and normalize poverty and violence and helping them become global sisters, program director LaKeisha Gray- Sewell, told The Final Call.

Mentoring for Black girls is critical, Ms. Gray-Sewell said, because “there are so many facets of our society that break our children down and don’t prepare them fully for their highest development. Mentors provide that; they fill in that gap that teachers can’t provide, that parents can’t provide, those other areas can’t provide. Mentors are also the mirror for young people of what’s possible,” she said.

L’Mani Viney, with the Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity’s Guide Right Program, said their group has the most extensive mentoring program in the country, boasting a cadre of 5,000 mentors.

“Our program is about looking at our young Black males as an asset, making an investment in them so that they can maximize their value,” he said. “Mentorship when it comes to Black youth should never be practiced as saviorism. Mentorship should be practiced as identifying the true potential and assets within the young person; it’s a collaborative effort,” he said.

“What I mean is to mentor Black children is about identifying their true potential in greatness, seeing that and in collaboration with them identifying resources like education that they need to maximize this greatness.” The Covid-19 pandemic has presented challenges when it comes to how programs are now functioning. Ms. Muhammad and her self-funded SWAP program had to suspend services. Some challenges have been turned into opportunities and those who work with youth agree there is probably more of a need for their programs now more than before given the covid virus and it’s impact on school and curtailing of social activities.

“The largest barrier has been in-person contact. I have not had the opportunity to meet with my group all year. We had to do a graduation video for my graduating seniors. We talk a lot, and we chat a lot, you know, we’re on Zoom a lot. We come from a culture of adversity so that we will persevere,” said Mr. Viney.

The Mentoring Male Teens in the Hood has not missed a beat. Mr. Miles states, “We haven’t had to stop. We’ve been meeting since July, we’ve taken two field trips. We couldn’t take a bus because we want to socially distance, so we have used vans. Everybody has to wear a mask, we social distance in all of our in-person activities.”

The Groove program has adapted according to Mr. McDougle. “To be safe and ensure safety, we have had to go virtual. So, then the other problem is the digital divide gap. So, some kids can have Zoom conference calls, and other children we have phone calls. In some instances, we have to drive by their house and talk to them through the window.”