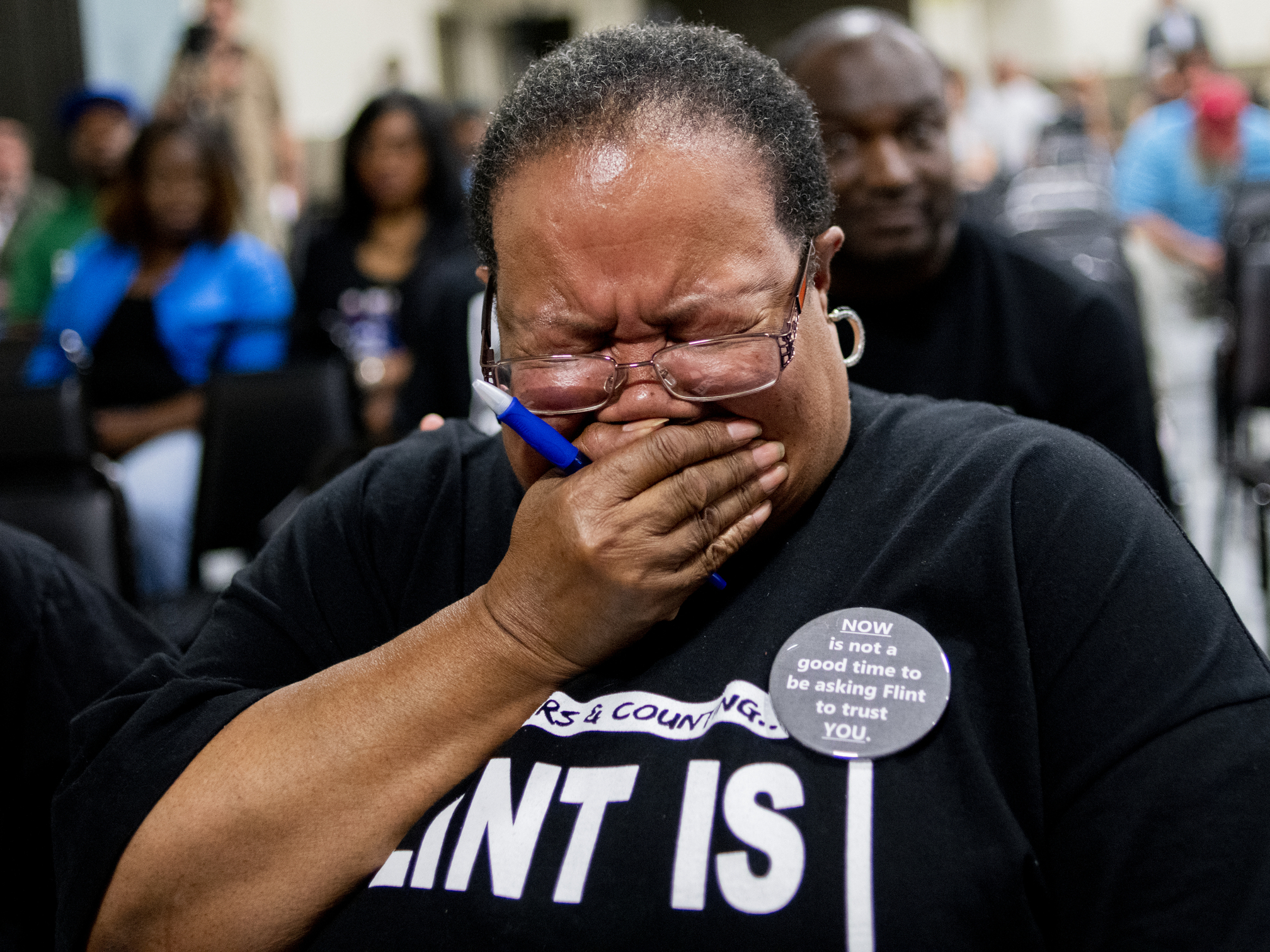

Water activist Audrey Muhammad’s grandson was born at the beginning of 2016, in the middle of a water crisis. He stutters and has speech problems. Claudia Perkins-Milton with the Democracy Defense League of Flint knew of a mother who had four bags of her daughter’s hair. Nakiya Wakes lost two sets of twins, in 2015 and in 2017. Children who were A students started making D’s. Adults lost limbs, broke out in disease, and died from multiple types of cancers and Legionnaires’ disease.

These are effects of the ongoing Flint Water Crisis, which started nearly seven years ago in 2014 when Flint, Mich., city officials switched the city’s water supply from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Flint River. Activists and residents are still fighting for justice.

On Dec. 30, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed legislation to establish a trust fund in order to distribute a $641 million settlement to Flint residents, but residents and water warriors question if the money is enough. Former Flint mayor Dr. Karen Weaver, Flint resident Arthur Woodson and Audrey Muhammad told The Final Call that the settlement is a slap in the face. After attorney fees and other expenses are taken out of the $641 million, the amount will be a little over $400 million.

Dr. Karen Weaver compared the settlement to a $500 million settlement given to 332 women and girls who were sexual assault victims of Larry Nassar, a USA Gymnastics doctor who worked at Michigan State University. “$400 million is nothing when you look at the number of people it needs to be spread amongst. We’re talking between 80,000 and 100,000 people,” she said. Flint, a predominately Black city, is located about 66 miles from Detroit.

The city of Flint and McLaren Regional Medical Center are putting $20 million each into the settlement, and Rowe Professional Services Co. is putting in $1.25 million. Flint City Councilmember Eric Mays told The Final Call that he is against the settlement because he doesn’t think it is fair and adequate. He provided the breakdown of the money. Almost 80 percent of the money will go toward children 17 and under, 15 percent to adults with personal injury documentation, three percent to people with property concerns and two percent to businesses. Out of the 80 percent going to children, children six and under will get 64 percent, children 7-12 will get 10 percent and children 13-17 will get five percent. The three percent category for adults with property damage has a $1,000 cap.

“If you got 30,000 or 40,000 adults with no personal injury documentation, when you look at four percent of maybe $400 million, that might come to $14 or $15 million at best. You divide $14, $15 million among 30,000 adult residents, you come up with a figure of about $530 something. That would be embarrassing for me, as a council person in the city of Flint, when you have people who have experienced the water crisis,” Mr. Mays said.

He listed factors of the water crisis, including racial discrimination, former Michigan Governor Rick Snyder and his administration intentionally not putting corrosion control as a treatment and the fraudulent taking control of the water by banking and bonding institutions. U.S. District Judge Judith Levy is currently reviewing the proposed settlement and its terms. Mr. Mays said they expect her to make a decision on the preliminary approval in the middle of January 2021. Once that happens, the plaintiffs, who are majority Black, can decide whether to object, file a claim or opt out of the proposed settlement.

“Many of us don’t understand that that’s the floor with the settlement. It’s not the ceiling. It’s not the most that we could have gotten. And they made those decisions without seriously considering the residents of Flint,” activist Audrey Muhammad said.

She said it’s frustrating that officials are trying to settle a civil suit before bringing criminal charges. “You expect us to go to the person who poisoned us to ask them for justice,” she said.

She listed other lawsuits that have yet to be determined and settled, including a lawsuit against the United States Environmental Protection Agency, one against the banks involved and one against people who were personally involved. She said though the legal process has been slow, environmental cases often take longer than five years to settle.

“This is a short term and you want us to settle for pennies. I say hold out and wait,” she said.

Activist Claudia Perkins-Milton talked about some of the effects of the water crisis. The infrastructure of many homes is damaged, and many people have damaged immune systems.

“We had pure yellow, pure brown water coming out of our bathtub, out of our showers, out of our sinks and you thought we were gonna drink that mess? And then at one point in time they told us to boil it, and that made it worse, according to the scientists. We just been jacked up all the way around the board,” she said.

Residents in Flint are still relying on bottled water, despite officials declaring the water safe to drink. “They say that there’s nothing wrong with the water that we’re drinking. People don’t trust it, mainly because they have not completed all the phases to repairing the water to make sure that we have safe drinking water,” explained Ms. Muhammad.

She said a few homes had lead service lines put in place but that nothing from the service lines to the water plant was replaced. She also said none of the plumbing in the homes have been replaced.

“I think some of that was supposed to have been included in the lawsuit, but there have been no settlements and nothing done from the city directly,” she said.

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel and her office dismissed all criminal charges in the Flint water crisis in 2019. The office released a statement that year saying it would launch a new investigation, but interviewees say they haven’t heard anything else.

Ms. Perkins-Milton is demanding for those who were involved with the water poisoning to be brought to trial and convicted. Black Millennials for Flint, an environmental justice and civil rights organization, started a petition for people to sign demanding a ruling of “no” for the $641 million settlement. Other demands include clean water, the repairing of pipes inside and outside of homes and residences, free health insurance for life that follows the individual even if they relocate from Flint and $1.5 billion in reparations.

“I feel overlooked. I don’t even feel represented,” said Flint resident Richard Jones. “I don’t feel represented. I feel that whoever is saying what we will be satisfied with don’t know us.”

Flint resident Arthur Woodson said if enough people opt out of the settlement, they can stop the class portion of it. “We got to bring attention to the judge and let her know that we don’t want this settlement. This settlement is not fair for the people who have suffered for close to seven years with this water crisis. I mean what would $1,000 do? $1,000 won’t even buy the hot water tank that you messed up. $1,000 won’t even give me back the money that I had to go pay for seven years for bottled water. That will not pay for the lives that were lost close to me, my cousin and my aunt, my friends,” he said. “So don’t insult me with this settlement and say this is it and you have to go for it. At some point in time, we in the Black community have to stand up and have to say we might be poor, we might be living in poverty. Y’all walked on us for all these years, but you know what? Today we take a stand. We don’t care.”

“What’s to lose? I mean, $500. That’s it. You can make that in one week on your job or taking bottles to the store,” he continued. “Stand up for our kids now because this is generational. This isn’t just about our time now. This lead, this poison, is generational. What about our kids down the road? Why are we going to leave it to where they have to stand up and fight for something that happened back in 2014 that they weren’t even a part of?”

He said there needs to be cancer cluster studies done and biomonitoring, which is the measurement of toxic chemicals in the body. Dr. Weaver has been in conversations about demanding free college education for children who were affected by the water crisis, paid internships and practicums to have people working in the city, economic opportunity and establishing parks and playgrounds to facilitate physical fitness.

“You poisoned us. Let’s not get it twisted. You all poisoned us. You poisoned this community. So how do we all of a sudden become responsible for what you did?” she questioned. “It’s like you arrest me for indecent exposure but you stole my clothes. Now how does that work? So, I think it’s absolutely awful. I think it’s absolutely awful, and that was why I always said that Flint wasn’t about water and it wasn’t about infrastructure. That’s just a symptom of the racism that goes on here, and not just here, all over.”

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan during a Dec. 12 virtual address to the Nubian Leadership Circle warned that a death plan is in motion that Black people and the poor must survive. This death plan is being carried out by enemies that are threatened by our rise and that the Covid-19 pandemic and underlying health conditions Blacks suffer that make us more susceptible to the virus is not by happenstance, he explained.

“How did we get in this condition? Did you know that there’s food that they prepare for you and me in the ’hood, that they kill us by zip code? When they know your zip code, they send the worst food in for us to consume. Flint, Michigan is not an accident. They’re killing us through the water. You’re a young man and have erectile dysfunction. I’m not meaning to be vulgar. But our old folks died with the ability to make a baby. You need pills. You are already on death row and don’t even know it.”

The water crisis in Flint is not an isolated incident. According to the American Water Works Association, 40 percent of the water infrastructure in the United States is considered poor. The American Society for Civil Engineers rated the country’s infrastructure, including water systems, a D+ in its 2017 infrastructure report card. Residents of several small cities in Georgia are fighting against coal ash from plants like Georgia Power poisoning the water.

Audrey Muhammad met with a pastor, Eugene Keahey, who exposed water contamination in Sand Branch, a community in Dallas County, Texas. In 2019, the pastor and several members of his family died in a house fire. His death was a ruled a suicide, and his wife and two daughters were declared victims of homicide. A few months before his death, he posted a picture to Facebook that said, “We all have secrets.” Ms. Muhammad believes he was killed because of what he knew about the town’s water contamination.

According to the Pulitzer Center, Matt Black, a photographer documenting water contamination across the country, has photographed Lowndes County, Alabama; Martin County, Kentucky; Denmark, South Carolina; Newark, New Jersey and a Navajo reservation in Arizona and New Mexico.

“That’s what happens to our communities. That’s how we get treated. They make money and then live outside of the city where everything is nice and safe and the air is fresh and the water is pure and the dirt is clean and all that kind of stuff,” Dr. Weaver said. “Then they ask you about Covid or do you have any underlying conditions? I told them, I said I’m Black and I live in Flint. How about that?”