“So, 2020 is officially the cousin that no one likes at the family gathering,” joked Clayton Gutzmore, a freelance writer based in Miami who has covered a wide range of Black cultural topics.

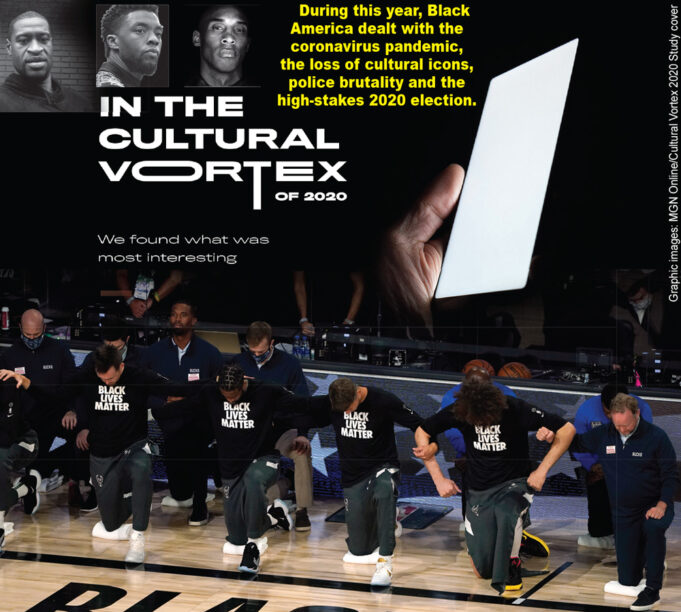

During this year, Black America dealt with the coronavirus pandemic, the loss of cultural icons, police brutality and the high-stakes 2020 election. Through those events, Black artists on all levels have allowed the social climate to influence the kind of art they created. In fact, it has influenced the country as a whole.

An annual study titled “In the Cultural Vortex of 2020” done by the advertising agency Butler, Shine, Stern and Partners, two of the most interesting moments of 2020 were the Black Lives Matter and social justice movements, along with the unforgettable legacy of Kobe Bryant.

With losses and gains, Black culture largely steered the entertainment world. But some also say it was the everyday man and woman who stole the 2020 stage.

A heavy start to the year

On Jan. 26, the country was hit with the news of the untimely death of legendary basketball player Kobe Bryant, and his 13-year-old daughter Gianna. Both Blacks and Whites felt a wave of sadness and shock, amplified by the tragic nature of the incident.

For Kolonji Gilchrist, founder of 21 Dreams, an artist collective based in Montgomery, Ala., the death of Kobe and Gianna brought a shift in perspective.

“Starting with Kobe, man, that was something that I think really put us in a mindset of nothing is for certain, for a lot of us, I think,” he said.

While on their way to a youth basketball tournament, Kobe and Gianna, along with seven others, died in a helicopter crash. Kobe left behind a wife, and two daughters.

“To watch somebody that had this beautiful career, had just gotten to a space where he was free to create, and everyone was really amped to see his next iteration of greatness and then for him to be gone, and his daughter to be gone, and imagine that void that was left in that household,” Mr. Gilchrist said.

Artistic tributes, as well as conversations from both former and current high-profile basketball players emerged as friends, family and fans mourned the loss.

Throughout the year, the country would lose other Black figures in the world of entertainment.

Chadwick Boseman, an actor who portrayed Marvel’s Black Panther, as well as other influential Black historical figures on the big screen, died of colon cancer on Aug. 28. On Dec. 23, John “Ecstasy” Edwards of the legendary hip hop group Whodini passed and a couple weeks earlier, actor Tommy “Tiny” Lister, who played “Deebo” in the popular “Friday” movies, died at the age of 62. Natalie Desselle Reid, who starred in B.AP.S., “Madea” and “Eve” died of colon cancer at the age of 53 on Dec. 7.

“We lost both Black major figures and we also lost essential figures as well,” Mr. Gutzmore said. “2020 really came through and took some beloved characters we all know and love. That’s one very dark part of this gray cloud that is 2020.”

Black Lives Matter, taking the world’s attention

Months after dealing with the emerging coronavirus pandemic, the somewhat hibernating issue of police brutality came to a national head at the end of May when the recording of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man dying in the custody of Minneapolis police, was released. It led to a summer filled with protests and demands for an end to systemic racism. It also brought greater attention to killings that happened earlier in the year, including that of Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man who died in an encounter with a White father and son, Gregory and Travis McMichael, while going for a routine jog in Brunswick, Ga., on Feb. 23. Also, there was the death of Breonna Taylor, a Black EMT who was shot and killed by police while they raided her Louisville, Ky., home on March 13.

The explosion in the streets bled into the artistic scene. Muralists documented pain on the walls of buildings across the country, paying tribute to those who died at the hands of police and White supremacy. Mr. Gilchrist and his group were among the artists responsible for murals in Montgomery.

“You definitely saw an uptick in the arts, mostly visual arts. Literary, too,” he said. “Artists that were connected to activism, they definitely were amplified, and those that traditionally haven’t been, started to find the space to create projects as well.”

Basketball players took part in protests in the streets before the restart of the NBA season on July 30, after coming to a halt because of the pandemic. The NBA and National Basketball Players Association made a commitment to use their platforms to bring attention to social justice.

“I was pleasantly surprised with the activism in the NBA. That was really … that was a lot,” Mr. Gilchrist said.

“The NBA definitely did what it needed to, the NFL followed suit,” Mr. Gutzmore said. “With the players having ‘Say Her Name’ on their jerseys and other things that’s tied to Black Lives Matter and all the unfortunate deaths that have happened here, to the NFL protesting and not doing practices because of all the stuff that’s going on.”

On Aug. 26, it was the Milwaukee Bucks that made a game changing move. The team made a major statement, opting not to play against the Orlando Magic in protest of the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisc. Other teams and players followed suit. For three days, there were no games played.

Eventually, Mr. Gilchrist said, players seemed to take stock of what they were doing and assess their reasoning.

“There was somewhat of a tug-of-war because people didn’t want to be doing something just to be doing it, or to make it so trendy, but to really ignite change to have some deliverables from that,” he said. “So then there had to be that chin check to be like, yo, this is cool, Black Lives Matter on our shirts and jerseys … but what action, what change can we make?”

On the musical front, artists including Beyonce, rapper Da Baby and singer H.E.R put out politically and socially-tinged music.

Melissa Hunter Davis, founder of arts publication Sugarcane magazine, doesn’t believe enough Black artists participated in the conversation.

“I think it was the everyday person that made people really, in particular celebrities, really made them fight for equality and to jump off the bandwagon,” she said. “We haven’t seen enough rappers and singers who have been out for a while, we haven’t seen or heard a lot of political music. The pop star who put out the most political music was Beyonce. And they didn’t follow her lead, which they would typically do. But they were too busy standing for her than really saying hey, we should speak out about this.”

Ms. Davis likened this to decades in the past.

“I think it should have been on a much broader scale,” she said. “If we look at the ‘60s and ‘70s, there was no one who did not talk about the civil rights movement.”

She said those who didn’t speak about it, “you could probably count them on one hand.”

“Even if they didn’t speak about it loudly, there was some work in the background,” she continued. “I felt like this year, we should’ve seen a little bit more.”

Mr. Gutzmore said celebrities shouldn’t be looked at as leaders in these types of conversations.

“An idea and thought that’s not talked about enough is how certain celebrities are looked at as the leaders, and that’s what we’re not supposed to be doing,” he said. “But because I guess they’re more of the people who entertain us, they’re more visible, we’re not seeing the people on the hill, the grassroots activists or anyone else who’s actually doing the work.”

But, he said, he is grateful for those who did take a stand.

“I’m grateful certain celebrities stepped up, became present when it came to the more serious issues. I’m also thankful for some celebrities’ honesty who actually admitted they’re not the ones [people] need to be looking at towards these types of major decisions and these types of essential conversations.”

One thing Ms. Davis was proud of was the way Black artists and entertainers pushed their way into mainstream media and brought attention to Black businesses.

The summer’s turmoil pushed many Blacks to support all-Black everything, and many Black celebrities helped to push that envelope.

Issa Rae, an actress and director, as well as actress Kerry Washington pushed for the support of Black businesses through social media. Pharrell promoted more than 30 Black-owned businesses in his music video for the song “Entrepreneur” featuring Jay-Z.

Some Black celebrities have also taken this year to move into a position of ownership. “Queen Sugar” star Kofi Siriboe launched his own media company; “Grown-ish” star Yara Shahidi along with her mother Keri Shahidi launched their own production company as well.

Rapper Ludacris stepped into the animation realm, creating a series called “Karma’s World” airing on Netflix. According to Variety, the series is inspired by his oldest daughter Karma, and is a coming of age story about a young Black girl using her voice to change the world.

“I’m pleased with how Black companies and Black executives and the everyday Black business owner was able to profit from people standing in solidarity and working towards buying Black and incorporating items and services from Black business owners,” Ms. Davis said.

The next generation of artists’ impact

A group of young artists in Detroit, Mich., is paying close attention to the events happening, and the conversations being had surrounding justice, said Quan Neloms, a school counselor and director of Lyricist Society, a program that helps middle and high school students use hip hop to find their voices.

“What I’ve been noticing with my students is they have become more concerned about matters that impact Black people like never before,” Mr. Neloms said. “I would say before, it would be like, they would’ve probably said, ‘everybody matters,’ but they’re becoming more concerned about Black issues, more concerned about their community, and the concern has turned into action.”

Part of that action is leaking into the art and music they create, Mr. Neloms said.

“A lot of my students were involved in actions in the city and when it came down to music production and what they wanted to talk about, they wanted to talk about those things,” he said.

Mr. Neloms likened this current generation to what he calls the Emmett Till generation. Mr. Till was a 14 year old brutally lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of whistling at a White woman.

“You think about that generation, 10 years old to 20 years old at that time. They saw themselves in Emmett Till,” Mr. Neloms said. “When they saw those pictures, it was so horrific. So the ‘50s, they were teenagers or adolescents and when the ‘60s came around … I don’t think it was a coincidence that the ‘60s was a time of social change and social turmoil. The civil rights movement was in high gear and I think it was because of that experience of that Emmett Till generation. And so as I think about it, I guess we can call this generation the “Covid” generation, or the George Floyd generation, or maybe even the Black Lives Matter generation … but I think it’s the same with them.”

He says his students particularly took notice of the actions of athletes, especially his male students.

“I think they have taken notice of it, especially when you had the high-profile athletes from the NFL, from the NBA … I think that’s the world that they live in, especially my young men. When you have a Lebron James or when they walked off the court and didn’t come out for the game, that was something that I think impacted them because they saw like, man, these guys are our heroes and they stand up for something.”

Looking to 2021, a year of action

With the packed year 2020 has been, some believe the issues faced this year will be amplified in art next year.

“To me, it’s reminiscent of what happened in the ‘60s. You could not be a cultural icon and not speak for the culture,” Mr. Neloms said. “I’m from Detroit, and Motown was the most pop music of its time, but even Motown had to switch from being pop music to making socially conscious songs. Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, even Sam Cooke. Sam Cooke was as pop as you could get, but in the ‘60s he had to make ‘Change Gon’ Come.’ So I think that, with our cultural icons, they’re definitely gonna have to speak for the culture. Of course, you’re gonna get the pop, you’re gonna get the fun music … but best believe they’re gonna be held to a standard of like, okay, we’re about this, too.”

Ms. Davis said she hopes to see more steady work next year.

“We need to make sure that elected officials, that people in the business arena and media and all different fields, that they continue toward what they say they’re about,” she said. “If you’re about Black liberation, if you’re about diversity and equality, then prove it. And we’re not going to let this be one performative act, we’re now going to make sure that you do this all the time.”

For Mr. Gilchrist, he hopes to see more unity among Black people and entertainers, and that both will continue to build.

“My hope, that we build from the stressors and things that came from this year and work collectively and continue to push culture and our communities forward,” he said.