by Naba’a Muhammad, Michael Z. Muhammad, Toure Muhammad, Tariqah Shakir-Muhammad, The Final Call Newspaper

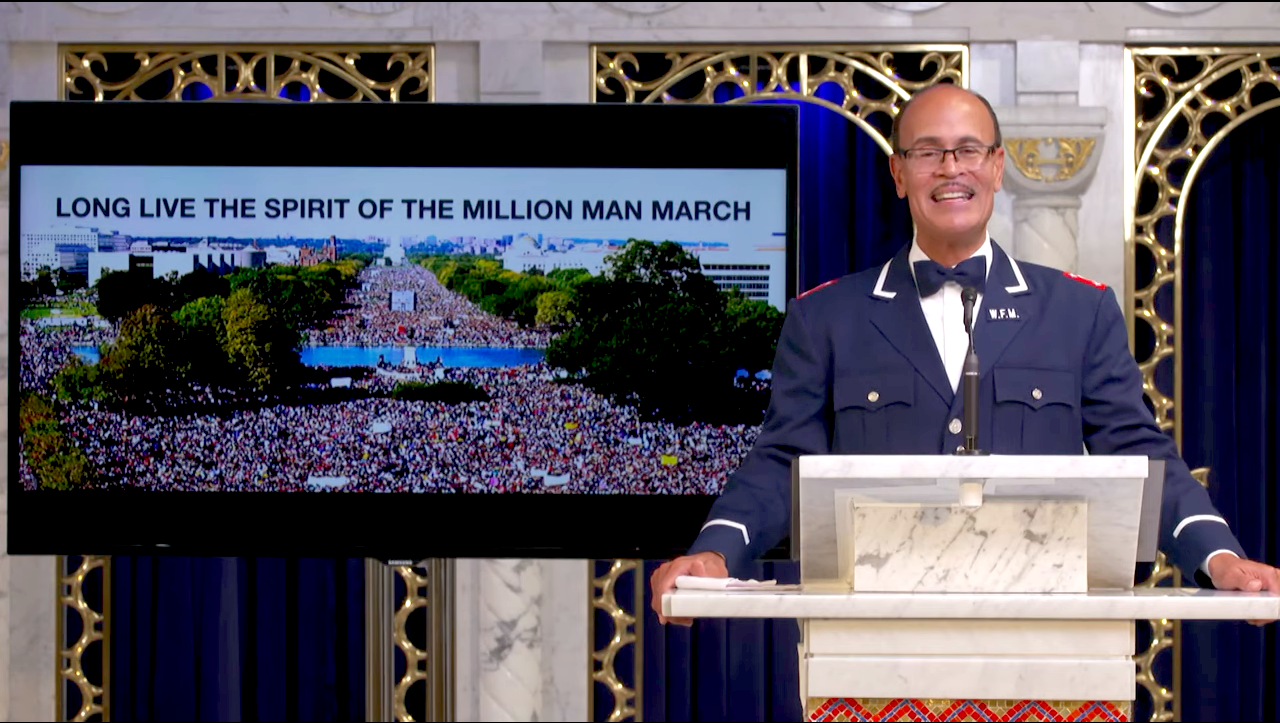

The 25th anniversary of the Million Man March brought remembrances, reunions, rallies, protests, breakfasts, documentary screenings and private moments paying homage to the “glimpse of heaven” seen October 16, 1995 on the National Mall and steps of the U.S. Capitol.

But those who came together didn’t just want to recall, most wanted to reignite the spirit, organization, energy, unity, and activity that made the gathering convened by Nation of Islam Minister Louis Farrakhan a success, despite overwhelming opposition from many quarters.

In Detroit, Rev. Wendell Anthony, head of the local NAACP chapter and Fellowship Chapel, and Nation of Islam Student Minister Troy Muhammad were among those remembering and restoring the March spirit and its redemptive and progressive work.

Events included a recommitment to the Million Man March Pledge to rebuild themselves, their families, and communities. As well as respect and protect women and children, act as community and world builders and business leaders, and to curb and not commit violence against their brothers except in self-defense.

Voter registration, like at the original March, was among the Motor City activities. The desire was to bring back the unity, which is needed, in very divisive times, he said. Student leaders took part in the activities and young people were honored for their efforts to make peace and community service.

Student Minister Troy Muhammad of Muhammad Mosque No. 1 in Detroit with members of the Nation of Islam and others participated on Oct. 16, the Million Man March Boys to Men ceremony.

He told The Final Call, “It also made way for men who attended the original March to pass on words of guidance to young men who weren’t even born when the March took place.”

He emphasized the importance of the youth being familiar with one of the most powerful moments in the history of America, where some two million men came together at the call of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan in 1995.

“It’s a beautiful day especially on anniversaries like this where we can come together and then hear those personal stories of men who changed their life during that period,” Min. Muhammad continued.

The awardees included young men who were also college and high school students, good fathers and activists within their communities. Stefan Perez, Troy Lumpkin, Zain Takkwul, Javon Harris, David Sadler, Dewann Robinson, Dorian Hardiman, Jr., Ameer Allah and Davion Floyd were among the recipients of the Boys to Men award.

“We also presented an award in the name of ‘Antonio Dumas’, a great young man murdered in the streets of Detroit,” continued Min. Muhammad. “His mom, Flynn Early, and uncle Shawn Early, were present to see us give the award to State Representative Jewell Jones, one of our state’s young, upcoming politicians.”

Also present to honor the young men were Reverend Wendell Anthony; Lieutenant Governor Garlin Gilchrist; Wayne County Executive Warren Evans; and Wayne County Sheriff Benny Napoleon.

The awardees were also given reading materials and suits.

Thirty-four-year-old Dewann Robinson said that the ceremony was a great encouragement for other youth to get involved in their communities.

“They can see what we can do, it gives you a glimpse of when brothers can just walk together of all ages, coming together to formulate a plan,” he said. “Basing it on those guiding principles, we can go ahead and show young men just in general, this is it. We put down orders of operation of how to deal with one another and how we value one another, but then also we show them to action.”

“We’re just grateful that the Honorable Louis Farrakhan was able to call—not a million, but two million men to Washington, D.C.,” Mr. Robinson continued. “That was just phenomenal, so we just really appreciate that so what we’re doing on Oct. 16 was carrying on the spirit of that anniversary when all those men came together and made pledges to do for their communities and families. It just really resonated within young brothers around the world, so I had a phenomenal time here.”

Life lessons from the March

In Birmingham, Ala., political leader John Hilliard told WBMA TV, “The Million Man March was so profound, it pushed me, literally, all over the globe,” added Mr. Hilliard. “I was determined to come home, register more African American men to vote, to talk about prison reform, to talk about all of the issues and actually the same issues that were going on then are the ones going on now,” the Birmingham city councilor told the local TV station. The March inspired him to keep pushing for change through political office.

WBMA also noted how the March “inspired the start of many community organizations with missions of mentoring, community building, anti-violence, and help with substance abuse.”

Writing in the Black weekly Chicago Crusader, writer Vernon A. Williams recalled how he arrived at the March. “Lining both sides of the small neighborhood streets leading to the mall, there were women and children waving and smiling and jumping up and down with messages to greet us. One handwritten sign read, ‘Thank You Brothers!’ Another read, ‘Sisters Proud of You!’ One in the back of the crowd read, ‘Real Men.’ And a small boy had apparently been handed a sign as tall as he was by some conscientious mother—held as high overhead as his tiny arms could stretch. It read: ‘My Role Models!’ ” he wrote.

“The Million Man March was more than a ‘feel good’ event. The day full of compelling speeches addressed critical issues of the day, such as an African-American unemployment rate twice that of Whites; a nationwide poverty rate of 40 percent for Blacks; Congressional cuts of $1.1 billion from the poorest schools in urban America. While White homicides at that time were 9.3 deaths per 100,000, the rate for Blacks was 72 killings for that same number of citizens. There were 200,000 more Blacks in prison than in college. Inner-city hospital closings jeopardized the health of men, women and children throughout the Black community. It was a serious point in history.

“And yes, Black men were urged to atone for their personal shortcomings and return to their hometowns with a renewed commitment to excellence. … What is indisputable is that it was a milestone in Black America, comparable to the March on Washington in 1963. And despite the violence in the vitriolic South that followed that momentous occasion, the lasting impact of such a show for unity, strength and moral direction had an impact that has lasted for generations. So did the Million Man March! It was the right thing for the right time. While Bill Clinton and his government cohorts were busy enriching the penal industry with an oppressive ‘three strikes’ program (for which the former president has since apologized) the Million Man March was there to remind us of our legacy of royalty, define our purpose and direct greater destiny.”

“When I attended the Million Man March, as a college student at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Ill., we faced threats from the local KKK that was based in the area, along with school administrators who refused to support our efforts to attend,” said Enoch Muhammad, founder of Chicago-based Hip Hop Detoxx. “Our overcoming those obstacles in 1995 and now reconnecting 25 years later with some of our supporters and those who traveled with us to D.C. was very energizing. This is providing the nearly two million Black men who attended an opportunity to recollect, recommit and repent so we can RE-UP our efforts to fulfill the mighty pledge that we as men took on the Holy Day of Atonement.”

“The online events we have been doing are important due to the lack of our recent historical successes being taught and popularized to generations who were not present and who need to know the context of what made the MMM happen and the actions that came as a result of the MMM, along with the counter-actions from our open enemies,” he added. He has spent almost the last two decades running the program that has taught self-knowledge, self-esteem, manhood training, life skills, and peace making through hip hop music to thousands of young people in Chicago and around the country.

In the Windy City, Student Minister Ishmael Muhammad delivered an introductory message Oct. 18 broadcast from Mosque Maryam, headquarters of the Nation of Islam, before Min. Farrakhan’s words from Oct. 16, 1995 were rebroadcast over www.noi.org.

During a roundtable discussion on WVON-AM radio 1690 simulcast over Von.TV, the radio station’s digital video platform, Final Call editor Naba’a Muhammad, contributing editor James G. Muhammad, staff writer Nisa Islam Muhammad and contributing writer Michael Z. Muhammad talked about the Million Man March and an historic 48-page edition of The Final Call newspaper devoted to the March.

“We don’t just want to reminisce; we want to reignite the spirit of the Million Man March given the challenges we face. We want to look back and take lessons in unity, organizing, self-determination and faith, we need today,” said Naba’a Muhammad, who also talked about the March and the special coverage in The Final Call newspaper earlier in the day on WVON-AM’s Perri Small Show.

The next day, Oct. 16, Von.TV re-broadcast the 1995 Million Man March.

Organizers in Chicago and speakers said the Million Man March was still important as a teaching tool and point of inspiration to compel action.

Just as Black women were a strong voice at the Million Man March, a strong Black woman gave a special message to the men. “Brothers, we need you to love on one another,” said Pastor Victoria Brady, president and CEO of ABJ Community Services and leader of Big Mama’s Movement. She urged Black men to come together in unity to stop the killing of Black youth.

Besides virtual sessions and March rebroadcasts, an outdoor gathering was held at the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum in the city’s Roseland neighborhood in Chicago.

“We care about our children, our babies. … This is an appeal to our brothers. We need you to do everything you can to stand united. The Big Mama Movement Chicago, we stand ready to support our brothers, our sisters and anybody that is going to do something about a 10-year-old being shot in the back (Oct. 7.) … Where is the march for that 10 year old girl that is fighting for her life?”

Lionel Muhammad, one of the event organizers, said, “This Holy Day of Atonement means reconciliation and responsibility. Those pledges that we took in 1995, we want to enforce that pledge and make a difference in our community and in our world.”

David Peterson, president and executive director of the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, was 14 years old in 1995. He attended the Million Man March as a high school freshman.

“The reason that it’s important that we convene here today 25 years later is because it was our obligation and instruction to take what we learned and experienced there and share it with our community,” he said.

Memories, motivation to act today

During an Oct. 15 broadcast of the nationally syndicated Carl Nelson Show over the Cathy Hughes-owned Radio One Network, Black men called in and shared how the March impacted the lives and still inspires them today. J.P., calling from the D.C.-area, shared how a Muslim friend encouraged him to sell March paraphernalia and shirts on Oct. 16, 1995. He was successful and the March sparked his ongoing business enterprises.

Others shared how peaceful the day was and one shared how he had preserved fliers, plans, documents, articles and publications from 1995 as part of efforts to perverse the March history.

The Black-owned Washington Informer newspaper captured some of the memories and ongoing commitments for the great day: “ ‘During the 1963 March on Washington, local Blacks were warned to stay away but we refused to do the same during the Million Man March. Black men came from everywhere because we understood that no matter where we lived, we were all facing the same challenges as Black men,’ ” said Hicks, 75, whose father, Bob Hicks, was the founder for the local chapter of a group called The Deacons for Defense, who carried guns to protect their community and marchers from angry and often violent Whites.

“ ‘Mayor Marion Barry, after hearing me talk about my father’s work and upon the advice of Ben Chavis, put me on the executive board for the March. I was then council president of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees for D.C.’s government employees comprised of 22 locals representing 22,000 employees excluding police, firemen and teachers. None of the major unions nationwide endorsed the March because Farrakhan and the Muslims were spearheading it. But because Chavis was in charge, our union chose to become the host union for union locals. Many locals who were predominantly Black came by the thousands from New York, Chicago, Detroit and California and it made a big difference.”

“Black men identified that this was something for us. The important thing about the March was it brought one million Black men together without the help of Whites. It made us feel like human beings, like men and good about ourselves.”

“I just remember the atmosphere and a calming energy as hundreds of buses filled with Black men of all ages arrived and the love that was being spread. Now, 25 years later, I’m saddened about what has happened since that day. Minister Farrakhan got us to come together without incident. It was all about brotherly love. We need to recapture that spirit again,” said another man who was a D.C. police officer at the time.

“More than 1,000 men from our church attended the Million Man March and it was a life-changing event. There was no crime, in fact the crime rate went down. Gangs put aside their beefs. It impacted every aspect of their lives. It affirmed us as Black men and it was probably the most affirming moment in American history for Black men,” one Christian pastor told the Informer.

KSAT-TV Channel 12 in San Antonio shared the story of two brothers, who worked on a March documentary and finished it just in time for the 25th anniversary. Des Moines, Iowa, saw the “Million-ish (Hu)man March” at the Iowa State Capitol on Oct. 17 calling for unity, ending racial injustice and including Black history in schools. Des Moines Register reported, “The Million-ish (Hu)man March, organized by the nonprofit Des Moines Selma, was modeled off of the historic Million Man March from 1995, where Black men from all over the country descended on Washington, D.C. promoting African American unity and family values. … ‘This is a spinoff of that march, but we are making it inclusive so everyone’s welcome,’ said Justyn Lewis, president of Des Moines Selma. … Lewis says he hopes the event will remind Iowans heading into winter that the Black Lives Matter movement is not slowing down.” Other participants included Laural Clinton of the Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement; Betty Andrews president of the Iowa-Nebraska NAACP; Abena Imhotep, a Des Moines Selma Board member; and Deidre Dejear, a former 2018 candidate for Iowa Secretary of State, the Des Moines Register said.

“We tell the powers that be what we need, we’re not asking. We have always been on the right side of the struggle,” Ms. Imhotep said. “Fighting for what is right, for what is true, honest, just and fair—don’t let anyone ever tell you that doing that puts you on the wrong side.”

In Memphis, there was a rally at I AM A Man Plaza that focused on voting and Black male participation. The original March registered men to vote and an additional 1.7 million Black men, inspired by the March, voted in 1996 national elections and turned the GOP out of office.

The Topeka Capital-Journal reported the Oct. 17 gathering led by Lisa Davis in the “Spirit of the Million Man March” and was in collaboration with the NAACP Youth & College Division, IBSA Inc., New Mount Zion Baptist Church, Black MentoUrs and Topeka Family & Friends Juneteenth Celebration starting from the Kansas Judicial Center and walking across the street to the State Capitol. Ms. Davis said as the men cross the street, each would have “a piece of paper with someone’s name on it, such as #GeorgeFloyd or somebody here in Topeka that has lost their life to gun violence.”

“I just think that it’s very important for people to see these Black men in another light than from when people have that negative stereotype,” Ms. Davis told the newspaper. The day’s focus is also on encouraging men with messages about how to change their lives. “We’re not marching. We’re not protesting. We’re recognizing and celebrating what was trying to be accomplished on Oct. 16, 1995,” she said.

Despite what seemed like overwhelming opposition, political condemnation, fearmongering, anti-March organizing, insults, ridicule, media attacks and efforts to pit Black people and Black men and women against one another, the March overcame all naysayers and critics as Black men stood proud in the sun Oct. 16, 1995.

The theme of the March was atonement, reconciliation and responsibility.

“The world thought we were down for the count when Min. Farrakhan called for the March, the world was able to see we were alive and well. We weren’t beat down or at the end of the road. Not only did we show up, but we also went home and did what he said to do,” said Minneapolis-based youth and anti-violence activist Spike Moss.

“It is particularly important that we not only remember it but do our very best to revive the spirit of the Million Man March when you consider we were able to do the impossible of bringing together all of the various segments of our community,” added the Rev. Willie Wilson. He was co-chair of the Washington, D.C. Local Organizing Committee. Rev. Wilson was also pastor of Union Temple Baptist Church at the time.

The 1995 March was held on a Monday. Participants were told to sacrifice to get there, not rely on others, to come unarmed, to come with a serious mind and to present their bodies as a willing sacrifice before God. They were to forego school, work and business to participate. October 16 was declared a Holy Day of Atonement and Day of Absence—no school, no work, no sport, no play—from a society that had devalued and oppressed Black people.

Commemoration of the March’s 25th anniversary started in earnest during the pandemic summer of 2020 in Columbia, S.C. Thousands gathered on Sunday, June 14, for a “Million Man March for Racial Justice.” It was a kind of reenactment of the original March. Participants were asked to come dressed in suits and ties, a style emblematic of the men of the Nation of Islam.

It was organized by ROAN Media Group (Rise of a Nation) member Leo Jones. He told The Final Call coverage of nationwide protests after the killing of George Floyd had, at times, shown Black men in a negative light.

Mr. Floyd died in police custody as a Minneapolis police officer, who was later charged with murder, sat with his knee on the Black man’s neck for almost nine minutes.

“So we decided to use the Million Man March as a model to help change the narrative about how we were being perceived in the media,” Mr. Jones said. “We collaborated with the Nation of Islam here in Columbia and received their blessing. We wanted to show who the Black man is; we wanted to register folks to vote and ultimately spread the Black dollar’s importance amongst our community. So at the end of the March, where 4,000 people participated, we raised $10,000 and registered over 1,500 people.”

A protest was held Oct. 3 in Annapolis, Md., to remember Black lives lost to police brutality and mark the 25th anniversary. In Boston, the Union of Minority Neighborhoods for Black Men’s Advocacy Day, State Rep. Bud Williams, and other partners planned a day of inspiration, brotherhood, and agenda-setting through an Oct. 14 virtual event. Mathew Parker, who helped organize the event, was a teenager at the time of the original March.

For the past 25 years, the Baltimore, Md., Local Organizing Committee has held a sunrise prayer service and breakfast to commemorate the historic March, said organizer Ertha Harris. This year’s event was held on Oct. 16 in Druid Hill Park at 6 a.m. Breakfast took place at the Arch Social Club, then men had a meet and greet for dinner. “Men of the March: Before, During, & After,” a documentary film commemorating the Million Man March premiered at the breakfast.

The March documentary dispels myths “tainting its legacy and reclaims the agenda of the March by sharing untold stories about their lives before the March, during, and after.”

Dr. Maulana Karenga, in a column published Oct. 15, in the Los Angeles Sentinel wrote: “(O)n this 25th anniversary of the Million Man March/Day of Absence, October 16, 1995, we must be careful not to forget or diminish the impact and importance of this great event of the 20th century. It was not just the brilliance and timeliness of the idea by Min. Louis Farrakhan, who rightly read the urgency of the historical moment; nor the size of the MMM/DOA in D.C., two million men and women, rivaled only by President Barack Obama’s inauguration. It was also the exemplary organizing work that went into it by the Nation of Islam and the local organizing committees which activists built in over 318 cities. And it was the important role of the National Executive Council and National Organizing Committee formed on the principle of operational unity and to reaffirm the openness to women, especially in the Day of Absence activities, but also in the March itself. And finally, the significance of this moment and Movement in history, was its impact on the men, as well as the women and community, their heightened political consciousness and practice, and their active recommitment to strengthen our families and our people in positive and concrete ways.”

Dr. Karenga, professor and chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach, is executive director, African American Cultural Center (Us) and creator of Kwanzaa, the Black American holiday.

A.T. Mitchell called for 500 good men from the five boroughs of New York to join him for the 25th anniversary celebration of the Million Man March sponsored by Man Up Inc., a Brooklyn-based anti-gun violence and community-based organization. The men came and played out their commitment despite a driving rain. Student Minister Henry Muhammad of the Nation of Islam mosque in Brooklyn spoke at the gathering. (See related story this issue.)

“I heard Minister Farrakhan loud and clear on October 16, 1995 when he said to go back into our communities and neighborhoods and join organizations and start organizations and to do the work that needed to be done,” said Mr. Mitchell. He founded Man Up, Inc., 16 years ago and with a bevy of efforts promoting employment and expanded business opportunity, mentoring, and education and personal and community growth and development.