For me, the Million Man March was a whole, exciting yearlong event, filled with exhilarating highs, and even some disappointing rejections.

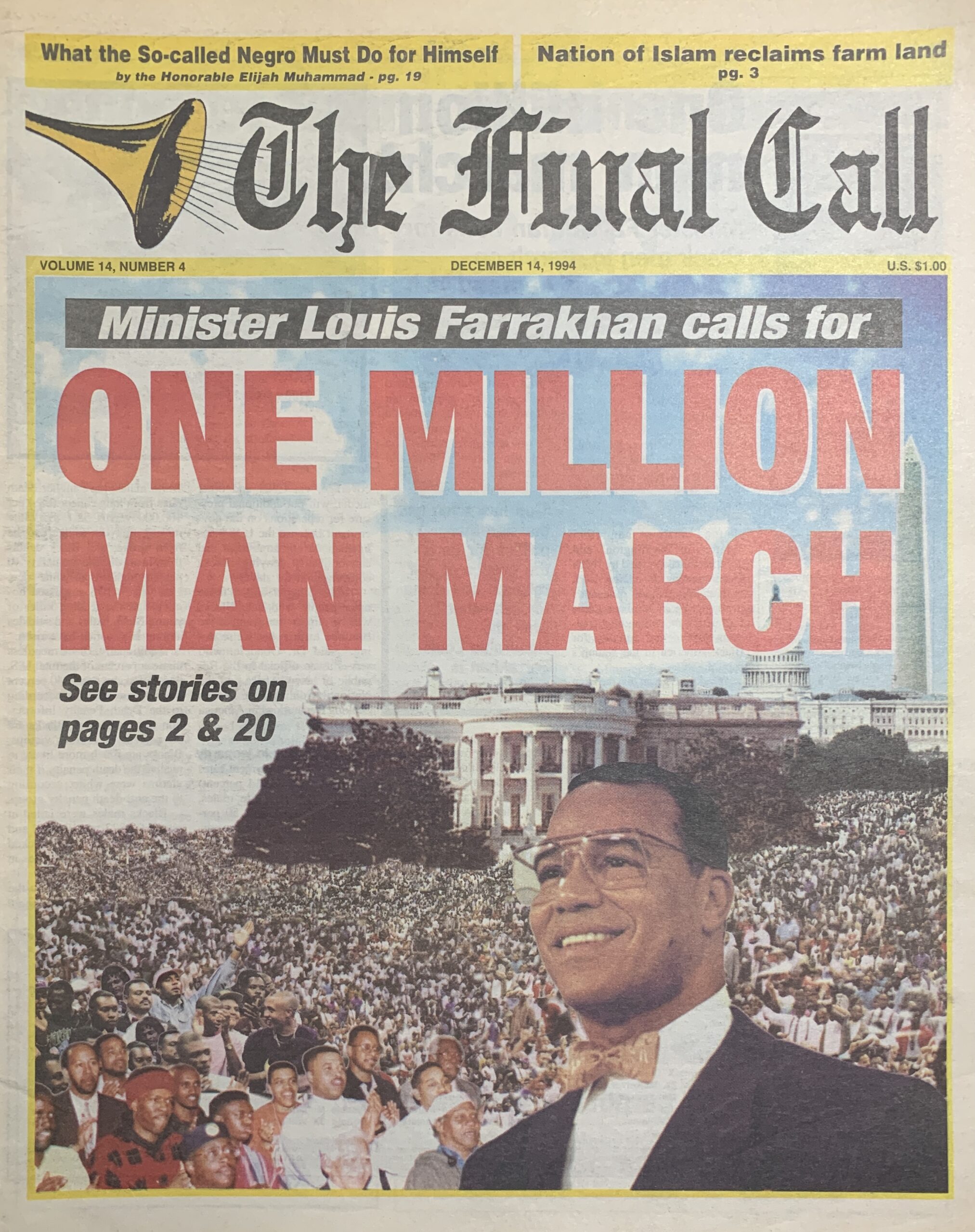

Although I had served the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad personally as Editor of Muhammad Speaks newspaper, meeting with Him in His home, first at 4847 S. Woodlawn, and then at 4855 S. Woodlawn in Chicago’s Hyde Park for two and a half years; and was there at the birth of The Final Call newspaper, working with the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan out of his home at 95th and Damen St. in Chicago’s Beverly Hills neighborhood; with his wife and business manager Mother Khadijah Farrakhan; his daughter and chief typesetter Sister Donna Farrakhan; his sons Mustapha and Joshua; Brother Wahid Muhammad, then National Secretary; Brother Abdullah Muhammad, the gardener, who would go on to become the Nation’s Prison Reform Minister; Mother Sumayyah Farrakhan, the Minister’s dear mother who left her substantial real estate holdings in Boston to live with her son and his family; and even Brother Kwame Touré (Stokely Carmichael), who always seemed to be a guest in the home when I was there to work on the paper; even though I was bathed in those deep, personal ties and fond memories, by the early 1990s, I was at an arm’s length from the day-to-day goings on of the Nation of Islam.

But I remembered, and always tried to obey the first instruction given to me by the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad: “See what’s good. See what’s bad. And look out for the interests of the Nation.” I remained a faithful witness to the good works being done by His Minister in His name.

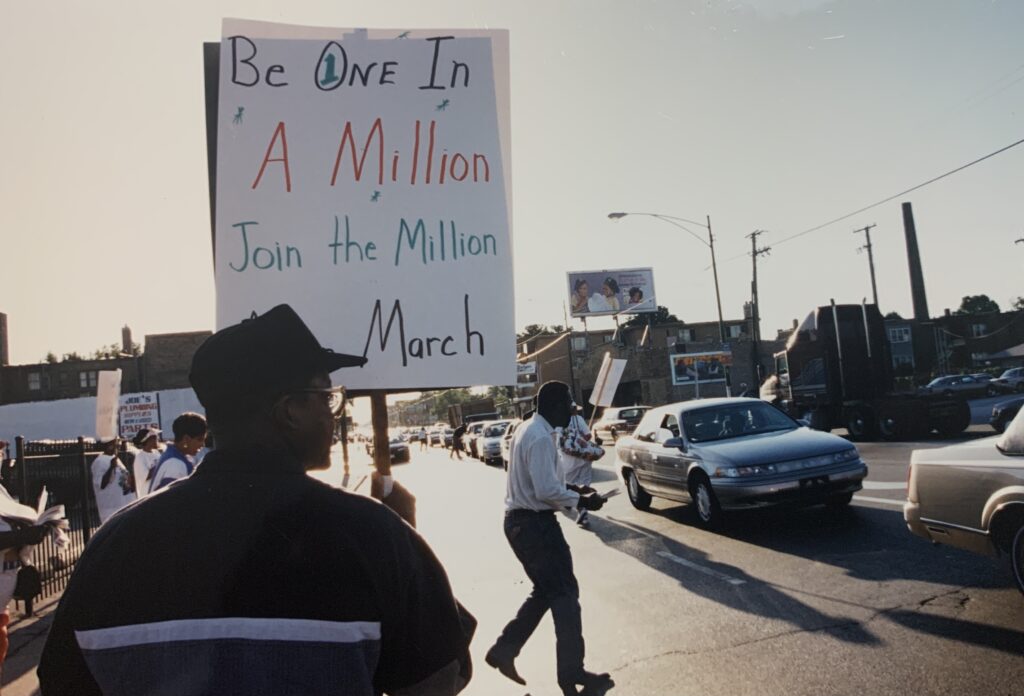

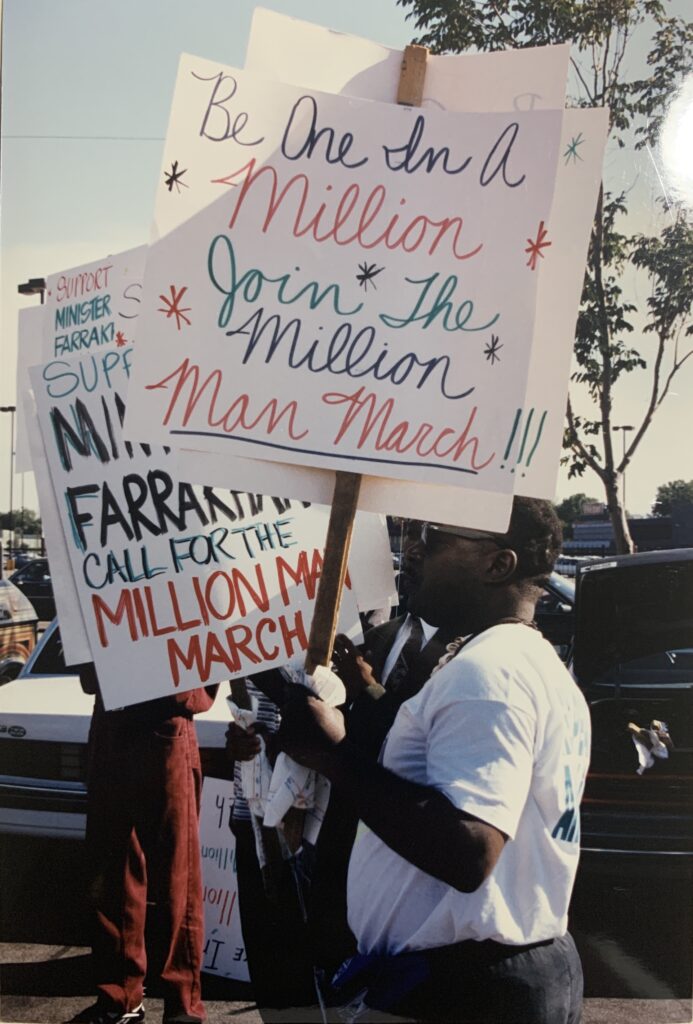

Like the thousands and thousands of Black men all over the country who were responding to Minister Farrakhan’s call for a rebirth, my spirit was quickened by his Men Only rallies taking place all over the country. It was at one such rally—at the Washington, D.C. Armory—where I realized that the March was going to be Big!

After the Minister’s inspiring lecture, charity was being taken, and the generous donors were being acknowledged. “Thanks to the men from Andrews Air Force Base for a donation of $1,000,” the announcer said.

I was shocked. You see Andrews (now officially Joint Base Andrews) is the super-secure military installation where the U.S. President’s and the official fleet of U.S. diplomatic aircraft is maintained. A delegation of men—all of whom carried the very highest security clearances just to be stationed there—a group of men assigned to that most elite military base in the country, were proud to make a sizeable donation to the cause, and importantly, were not ashamed to announce their affiliation publicly.

I knew then and there that the call for the Million Man March resonated proudly, not only in my heart, but in the hearts of Black men on every level, everywhere in these United States, and that the March was destined to be a crowning success.

Shortly after that, my friend, Imam Ghayth Kashif of Masjid As Shura in Southeast Washington arranged for me to be invited to an Islamic conference somewhere in Michigan. The state of Michigan is home to the largest concentration of Muslims anywhere in the country.

I was honored to accept the invitation. Then, as now, one of the most contentious issues being discussed there was the relationship between the “indigenous” Muslims, those born in this country—primarily Black and from “modest” homes and lifestyles who were converts to the faith—and “immigrant” Muslims, who were generally well educated, financially stable, and generally well versed in Islam from birth.

I thought I knew an answer that might help the sponsors as well as the native-born Blacks in attendance, primarily followers of Imam Warithudeen Muhammad, find common ground. At a session on Wednesday of what was to be a weeklong conference, I announced that later that year, in October, there would be a very special event which all the attendees should look forward to and support—the Million Man March, called by Minister Louis Farrakhan.

Well, you could hear a pin drop after my announcement, and after that I was literally shunned for the next three days! At meetings, at Friday’s Salatul-Jumah, it was as though I was invisible.

And so it was with my career in journalism. Officially I was a “freelancer,” which is a euphemism for being unemployed. I barely sustained myself with gigs in non-commercial radio and television and the independent Black Press. I appeared most weeks on Howard University’s WHMM-TV32 (now WHUT-TV) on the popular “Evening Exchange” program. I occasionally did commentaries which appeared on National Public Radio’s (NPR) “All Things Considered.” Less often I did commentaries which appeared on Christian Science Monitor Radio’s “Early Edition.” I was also featured, producing several documentaries for the national radio series “Soundprint,” including one—The Education of Charles 67X—about some of my experiences with the Nation in Chicago.

My most reliable, though most modest in compensation, was a column I write each week in The Washington Informer, a prize-winning Black newspaper founded by Dr. Calvin Rolark, who also founded the United Black Fund. Rarely, I was able to write an op-ed for some of the more prestigious White, corporate-owned newspapers—The Washington Post, The Baltimore Sun, USA Today, among them.

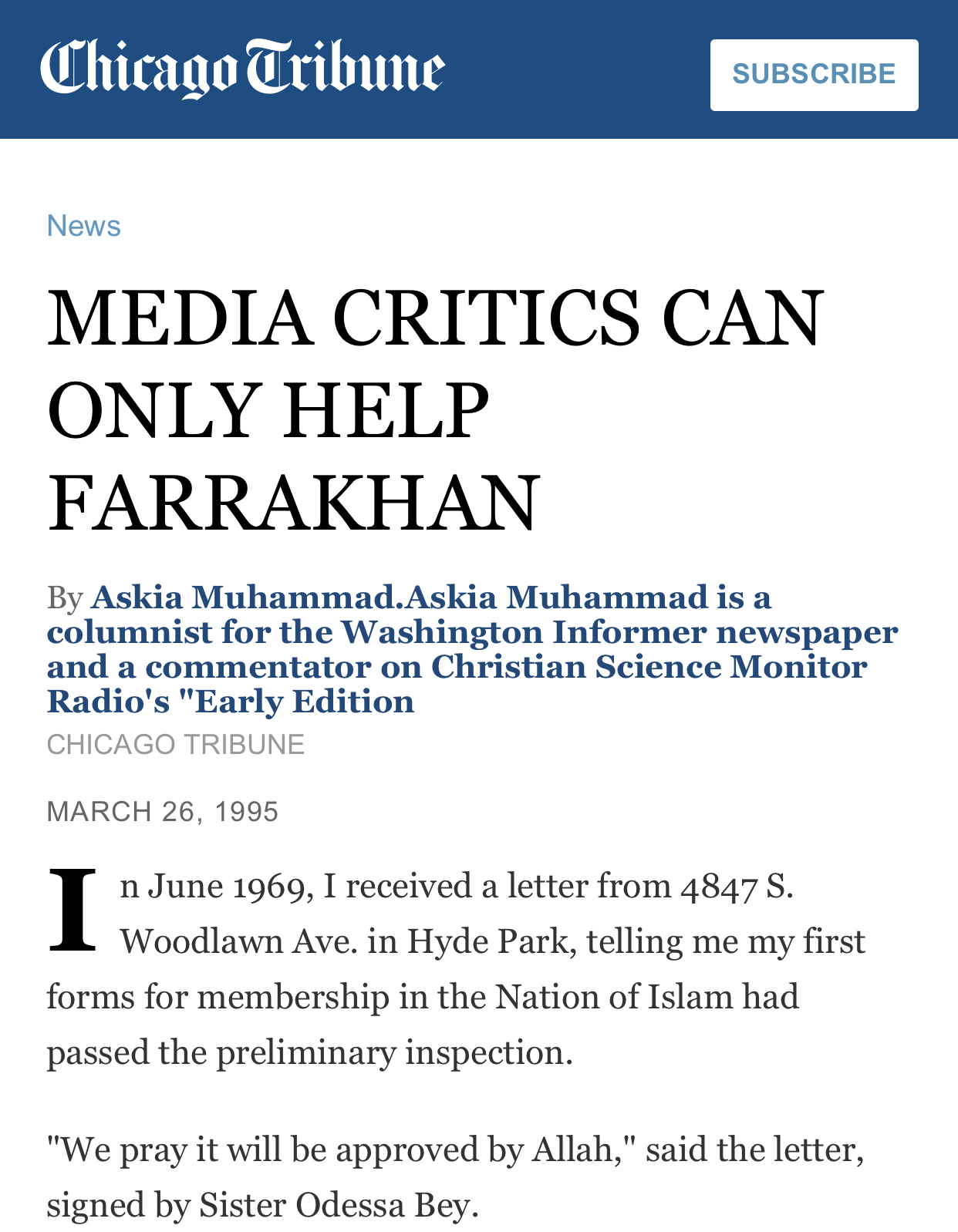

Shortly after my Michigan rebuke by the Muslim community at-large, I wrote an article “Media Critics can only help Farrakhan,” which appeared in The Chicago Tribune on March 26, 1995.

“What Farrakhan teaches is good for everyone because it literally ‘changes the minds’ of this society’s worst-off and most dangerous members—the descendants of Blacks who were brought to these shores in chains,” I wrote.

“In 132 years since Emancipation, America’s Blacks have progressed from slavery, to life as a permanent underclass whom no one seemed able to revive to productive participation. No one, that is until Farrakhan resurrected the teachings of Elijah Muhammad,” the Tribune published. “The White press can’t hurt Elijah Muhammad,” and by extension his representative Louis Farrakhan, I wrote.

I felt vindicated in front of the Muslim critics who had scorned me.

Throughout 1995 the build up toward the Million Man March grew. None of the major male Civil Rights leaders signed on, only the hard-core Black militants and scholars—Dr. Maulana Karenga, Dr. Conrad Worrill, Haki Madhubuti, Dr. Ron Walters—although prominent women, including Dr. Dorothy Height, Dr. Betty Shabazz, Mrs. Rosa Parks, were quick to join on and steadfast in their support for the March.

In September, 1995, Dorothy Leavell, publisher of the Chicago New Crusader newspaper—which had published the Honorable Elijah Muhammad’s “Mr. Muhammad Speaks” columns in the 1950s, before there was a Muhammad Speaks—and president of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, invited me to be a member of a press delegation travelling to troubled Nigeria which was inching toward political chaos under the leadership of Gen. Sani Abacha, who had seized power in 1993.

During a visit in 1994, military forces surrounded a venue in Lagos, preventing Minister Farrakhan from delivering an address. Leading opposition figures were imprisoned, protests in the oil-rich Port Harcourt, Rivers State nearly cut off the country’s main source of income. We were invited to help paint a positive picture for the outside world. We saw. We reported.

As we were leaving the country, I made an impassioned appeal to the government’s diplomatic escorts who had been with my party for the entire trip, that they should pay attention to what was about to happen in the United States, and that if they wanted to put their finger on the pulse of Black America, they should embrace the Million Man March.

The brothers listened politely to my pleas, but seemed unfazed. Our group returned to New York on Oct. 3, 1995, the day the Los Angeles jury acquitted O.J. Simpson of double murder, and for all practical purposes, Nigeria was wiped from the nation’s front-page headlines. But back at home, our attention turned again to the Million Man March.

Perhaps my greatest disappointment was when NPR rejected my commentary about the March. I argued that for the first time in more than 50 years, the “body” of Black discontent at last had a Black “head”—Minister Farrakhan.

My editors rejected me. The producer would have none of it. Finally, I was making my case with Ellen Weiss, the executive producer of ATC. The major Black protest marches had never before had a Black “head” I argued. In 1942, my uncle Nate Moreland, a lefty pitcher in California’s Mexicali (Negro baseball) League, arranged a tryout for Jackie Robinson and himself at Pasadena City College with the Cleveland Indians. Neither player made it to the Bigs. Uncle Nate complained publicly that he couldn’t play baseball in this country, but was called to fight in World War II, but he could play in Mexico, where he wasn’t required to fight.

Earlier, A. Phillip Randolph, the genius behind the 1963 March … Justice was organizing a massive protest in the nation’s capital, until President Franklin Roosevelt and Fiorella La Guardia, the Mayor of New York called him and personally persuaded him to cancel the Black protest because of national security concerns. Because of White influence, the march never happened.

In 1963, I told Weiss, when the March did take place, it was White labor money, and the feelings of president John F. Kennedy which influenced the proceedings more than anything else, even requiring John Lewis to hastily rewrite his speech, backstage at the Lincoln Memorial, so as to not offend the White president.

Then, I said, in 1993, at the 30th anniversary commemoration of the March, Minister Farrakhan—who had spoken in 1983 at the 20th anniversary commemoration—was told he could not speak, after having been invited, because of a letter sent to the Black Civil Rights leaders by Rabbi David Saperstein, of the Religious Action Center for Reform Judaism in a confidential memo on Aug. 13, 1993, just two weeks before the march. “What a devastating blow (a speech by Minister Farrakhan) would be to the solidarity of the coalition supporting the march,” the rabbi wrote.

This I said, was clear evidence that up until 1995, all the major Black protest marches had Whites at the head. “I have to stop you right there,” the executive producer told me. “David is my husband.” It would be nearly six years—after the 9/11 attacks and President George W. Bush’s belligerent saber-rattling in response—before my voice was heard again on NPR.

But I was blessed to trumpet my support for the March a final time in the corporate media. On Oct. 8, 1995, I wrote an op-ed which appeared in The Washington Post. “This demonstration for the first time was a ‘Black thing.’ It took hold via a new, all-Black infrastructure of financing, organization, and information dissemination,” I wrote.

“Rather than continue to lament that disparity, this march sought to change it by empowering a new grassroots Black leadership. It latched on to the same source of discontent that drove the now-defunct Civil Rights movement: unequal treatment of African Americans. But rather than challenge White leaders for control of the Civil Rights groups that Whites helped found, the Black organizers of this march replaced the integrated head on the Civil Rights movement’s Black body with a Black head.” The stage was set.

And when the sun rose over the U.S. Capitol that Monday, Oct. 16—136 years to the day after John Brown and 21 others, including five Black men and three of his sons attacked the U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry (then Virginia), lighting the fuse of the Civil War which would end in the abolishment of slavery—more than 250,000 men had already assembled there, before dawn, on that brilliant day in Washington, when the fuse was lit, igniting the greatest, peaceful revolution in U.S. history.

It was the beginning of the Third U.S. Reconstruction. It was the beginning of the Third Resurrection of the Nation of Islam. It was the magnificent Million Man March, and I thank Almighty God Allah, that I was there, and that I had seen it coming from a long way off.