Almost two million men attended the Million Man March at the call of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan 25 years ago on October 16, 1995, but behind-the-scenes and out in front, women worked, organized, supported, spoke and women were impacted.

One of the earliest supporters of the Million Man March among Black women leaders was Dr. E. Faye Williams, who today serves as president of the National Congress of Black Women. She was in charge of the weekly organizing meetings and was co-convenor of the Washington, D.C. Local Organizing Committee (LOC) and co-chair for the March.

“There were some people who were concerned that it was biased against women, to say they we’re having a Million Man March. Of course, I didn’t feel that way. I felt that it was a really good time for brothers to get together and to be more positive, to strengthen themselves and to be better men. So it was not a problem for me from the very beginning, and it didn’t matter to me, some of the negative things that people were saying because women were not invited,” she said.

“It’s just that we weren’t openly invited, but we were not told that we could not show up, and that was one of the first things I said to Minister Farrakhan when he came to town to talk about what the march would be like,” she continued. “I raised my hand and I said, ‘Minister, I love you. I respect you. But I just can’t see having a million Black men come into town and I’m going to stay home, because I don’t have a husband or children to stay home with.’ He kind of chuckled, and soon thereafter, I was asked to be one of the co-chairs of the March.”

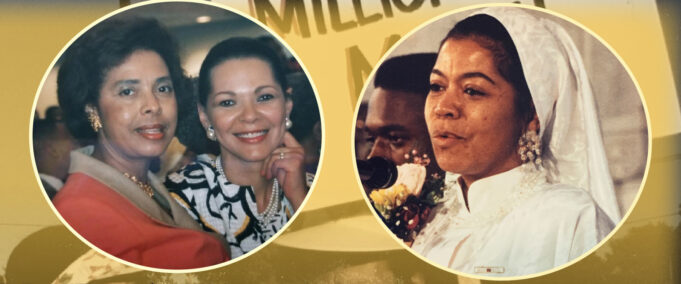

Ruth Muhammad also attended many of the early organizing meetings for the March. She was a photographer, great helper, planner and organizer for the Nation of Islam’s Mosque No. 4 in D.C.

“I was able to attend one of the first national planning sessions convened by Minister Farrakhan at the Kennedy Street fraternity. It’s the Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity house headquarters that became the headquarters of the Million Man March. And some of those in attendance at that meeting was Cora Masters Barry, the wife of Mayor Marion Barry, Rev. James Bevel, Rev. Al Sharpton as well as national officials of the Nation of Islam,” she said.

Ruth Muhammad attended meetings with the National Park Service which provided park parameters and guidelines to follow. She also assisted Dr. Abdul Alim Muhammad with the health task force for the March, attended meetings held by Dr. Dorothy Height, who was president of the National Council of Negro Women, and attended planning sessions at Union Temple Baptist Church under the leadership of Rev. Willie Wilson and Rev. Mary Wilson and meetings at the Imani Temple African-American Catholic Congregation under the leadership of Archbishop George Augustus Stallings who had previously broken away from the Catholic Church for what he charged was its failure to serve the needs of the Black community.

Outside of the meetings and planning sessions, Ruth Muhammad also assisted Mother Tynnetta Muhammad, wife of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, patriarch of the Nation of Islam. Mother Tynnetta Muhammad convened a team of sisters to produce a book, “Women in Support of the Million Man March.” Ruth Muhammad brought up a section in the book, which addressed the questions: “What is the role of the woman? What are some ways that we can help?”

When the March started out, there was a thought that it was a march for Black men to bring them together. Min. Farrakhan had crisscrossed the country conducting “Men’s Only” Meetings to encourage them to stand up as husbands, fathers and responsible protectors of their families and communities. “The March was one of the culminations of all of these meetings. But the sisters, the women wanted to know, OK this is great, but what is our role? What can we do? Because these are our brothers, these are our fathers, our sons, and we’re affected by whatever affects them,” she said.

“I remember there was a time when attorney E. Faye Williams asked about that: what can women do? So the Minister said you can support. There’s a way for you to support the men without being a part. We’re not saying the Million Man March is not for women. We’re saying we as men, there’s a unity that we need to forge, first. So, he gave us different ideas of what women can do,” reflected Ruth Muhammad.

Women did much of the planning and organization for the march, including registering people to attend and raising money for donations.

Black women used their voices on radio and television to help promote the Million Man March. Radio talk show host Bev Smith was one of the women who promoted the march. She hosted both a radio show, called “The Bev Smith Show,” and a popular show on BET (Black Entertainment Television), called “Our Voices.” At the time, BET was Black-owned by Bob Johnson.

“Women pretty much agreed to let the men come out front. This is what I talked about on my show, that we needed our Black men to show strength,” she said. She said she felt that was her role because of the way White media outlets portrayed the March and how they predicted it was going to be violent.

“I made my show ‘the voice of the Million Man March.’ The Minister gave me permission to do that, and that’s what I did,” she said. “And then I did public service announcements on my own and recorded them, trying to get Black men to pool their resources and get buses and stuff like that. Because it was something to see. It was something to see. I’ll never forget it. To see all these men, and I’m absolutely convinced it was more than a million. It was more than a million men. They have to cut it. It was more than a million men. There were men everywhere. And what I also loved about it is that the women gave the men faith,” said Ms. Smith.

On the day of the March, women in the Nation of Islam helped make sure the March was secure. Those who were not doing security stayed home. “It was a day of absence from your jobs as well, because the march was on a Monday, and that was historic in and of itself,” Ruth Muhammad said. “So by not being present in the world but being home and being a supporter was very radical for that time, for people to say, ‘No, I’m just going to be supportive. I’m going to stay home.’”

The March was a surreal moment for Black women. Many went out of curiosity and to be a witness of so many Black men gathered together.

“The next day, my phone never stopped ringing. They were like, ‘Girl, that was something. … Weren’t those brothers fine?’ And they were. Some fine brothers. Tall, marching beside each other, shaking each other’s hand, hugging each other,” Ms. Smith reflected.

Dr. Williams’ best friend was one of the women who attended the march. “Black women were just so excited to see Black men … stand up and want to do better than the public sometimes viewed Black men,” Dr. Williams said. “They wanted to see them in a positive light, and that day offered us an opportunity to see all these beautiful Black men out there seeking to do better in our community.”

Filmmaker Stacey Muhammad worked at the official Million Man March headquarters on Kennedy Street. She was a part of Dr. Benjamin Chavis’ national organizing staff.

“The experience being an organizer for the March is one thing, but to step foot on the National Mall that morning and to see those men and women but mostly men the Minister asked for there, to be present and responsible and follow the Minister’s call was a beautiful life-changing experience. I don’t think any of us had ever seen anything like that,” she said.

She and others helped Dr. Chavis, who was national director of the March and who today is president and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, an organization that consists of 200 Black-owned newspapers. Stacy Muhammad also helped Dr. Chavis write his speech for the Million Man March.

“We were helping him write his speech like the night before. I think we hadn’t slept in a good 48 hours. And the Minister was in town, of course. It was just so exhausting up to that day, because there had been so much work. We didn’t sleep. The anticipation was just that intense,” she said. “Of course we trusted the Minister’s word, but to actually see that many men early in the morning and even watching the news and see all the buses lining up or all the buses coming in. It was like, oh my God, all these people are actually coming! And I remember getting there probably at three or four in the morning and just being speechless by the number of people that were already on the mall at that time,” Stacy Muhammad reflected.

At the 1963 March on Washington during the height of the civil rights movement, Black women were part of the planning, but none spoke that day. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis and other men spoke. But with Black women being so heavily and critically involved in the Million Man March, that day was a day for them to speak to their brothers who had gathered at the Mall. Dr. Cora Masters Barry; Dr. Betty Shabazz, wife of Malcolm X; Mother Tynnetta Muhammad; Dr. Dorothy Height; Rosa Parks; Queen Mother Moore and Dr. Maya Angelou spoke that day to the over two million Black men who gathered. Ten-year-old Tiffany Mayo recited a poem by Dr. Angelou.

Dr. Williams didn’t know she would speak on the program until the night before.

“When I learned that I was going to be asked to speak at the Million Man March, imagine my excitement to be able to do that. It was my role to talk about people registering to vote and voting and also calling the names of some of our historic leaders so that we could remember them on that day,” she said.

Angela Muhammad, also a filmmaker, used to go to the March headquarters building to help with paperwork and make phone calls. She graduated from film school at Howard University and later on produced a documentary of the March in 2010 for the 15th anniversary.

“I was married at the time, and my husband went. Just being able to be a part of something that captures that and hearing brothers talk about that experience when they were there, it’s really exciting. I was able to meet different artists, different people who are known in history. Dr. Dorothy Height. I had the opportunity to interview her,” she said. “I met Ice-T, Chuck D from Public Enemy and others. It was just exciting to meet them and hear them talk about it, and then of course the main one was the Minister. We were able to get an interview with the Minister. Words can’t even describe that feeling. He definitely makes you feel special. He called what we were doing a noble work.”

She said when her husband went that day, he returned home late. “It was real late when he did make it home. But it was like, I don’t know, like they were on a cloud nine for, you can’t even say days. Maybe weeks. Even months for some brothers. I know some brothers still when they talk about it now, you can see them going to cloud nine when they reminisce about it 25 years later,” she said.

Her documentary, “The Million Man March: The Untold Story,” was picked up by Kweli TV, founded by DeShuna Spencer. Angela Muhammad is showing it for free via Zoom and YouTube live on October 16.

While she captured the March after it happened, Ruth Muhammad shot many of the historic photos of the October 16, 1995 March. On the morning of the March, she was stationed with the health task force at Imani Temple, and many people would stop by to ask questions on how to get to the March.

“At some point during the morning, some of the VIPS came to that location and required an escort to the Million Man March stage, and a FOI (Fruit of Islam, men of the Nation of Islam) was able to drive us from the temple to the March staging area as close as he could get, but we had to walk the remainder of the way. And as we walked through this crowd, the men attending the march, they just parted the way. It was like the Red Sea parting,” she said.

“Once the VIPS were settled on the stage, I got a chance to turn around and look at the crowd. It was so overwhelming. The crowd size, it was so overwhelming. And then I saw Brother Naba’a, who afforded me the opportunity to walk to the top of the Capitol steps in which I was able to turn and I was blessed to take one of the historic photographs of the Million Man March,” she reflected.

It wasn’t until she printed the photo that she really looked at and noticed it. “I’m like oh my God, look at all of these people. They were in the trees. They were on top of buildings. The kids were sitting on their fathers’ shoulders. There were older men, younger. I mean, it was just so incredible, and it was something that your eye can’t, your heart can’t hold but so much,” she said.

“It was just an overwhelming event. Even as we can talk about it 25 years later, it still holds such a big place in my heart, that because of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, I was even blessed to be a part of much less have an opportunity to record and to photograph.”

The Million Man March had a lasting impact on the Black community. “I know that the March had a lasting impression on a lot of people. For years I could see the difference in many of our brothers in terms of their respect for women, their courtesy, their respect for each other. And we were all calling each other brother and sister,” Dr. Williams said. “There are days now, I just wish every time I see something negative happen, that all of those people had come to the March, because I think they would have a different view of each other and would never do anyone harm but would always be willing to help, whether it’s a brother or a sister. I know that for me, the impact of that day will never go away,” she added.

She saw brothers go out and search for their children and start taking better care of their children, and she noticed that other races had a newfound respect for Black people. She said if young people saw what happened that day, it would resolve some of the challenges they face. “I believe they would change if they saw what happened that day and to know our possibilities of being more positive and supportive of one another,” she said.

Bev Smith said for awhile after the march, Black people came together. “They came together, but I have not seen them like that since, except for the murder of George (Floyd) and Breonna (Taylor). It’s starting again. But what we need internally, that means Black folks, internally, is we need to call for unity,” she said. Ms. Smith said the day after Million Man March, people were still lingering around in D.C.

“A lot of people from out of town didn’t leave the next day. They stayed one more day. There was a feeling in the atmosphere. It was so strong. … It was a love and a respect,” she said. “When we went back downtown the next day, there were people still talking about it. ‘Were you there?’ That was the question everyone was asking. ‘Were you there? Were you there?’ It was wonderful. It was wonderful. And I’ve marched all my life. And I love Dr. King, and I was a student of his movement. I’m telling you, it was nothing like that Million Man March.”

Stacey Muhammad said the energy in D.C. was really high the day after. “My friend … he’s telling us this story about these brothers going into the barbershop the day after the Million Man March, and it took them so long to get in the door because they kept saying ‘no you first, no you first, no you first,’” she said. “It was just so much consideration of one another. Just simple human things that people have a tendency to overlook. I think that was high amongst Black people, particularly Black men, right after the March.”

She said a lot of the Local Organizing Committees turned into nonprofit organizations. Angela Muhammad said brothers joined the Nation of Islam as a result of the March, and one brother started an organization where he worked with young Black men on Bowie State University’s campus. The organization is still going today. Ruth Muhammad knew a brother who adopted two sons after the Million Man March.

“You know that there is an impact. You don’t know their names. You don’t know where they went back to, but you can only imagine over a 25-year period where they’ve gone to and the different impact it’s had on their part of the community, on their families,” she said.

“For me being able to have these photographs, I was able to make up posters, and I would go to different places and I would see people and I would say, ‘Oh, did you attend the Million Man March’ and they’re like ‘Oh, yes,’ and then they would tell me their story about their experience and who they attended with and what it meant to them and I would give them a poster. For me, it was like a continuing gift to us to know that it happened,” said Ruth Muhammad.

She attended the Million Woman March two years later in 1997. She described it as an extension of the Million Man March through the voices of women. Some of the women, like Dr. Williams, are still being asked to speak on panels. Ruth Muhammad said she will be on a panel for the 25th anniversary along with Dr. Chavis, Mark Thompson and others. Many of the interviewees for this article said they wish there could be another Million Man March. “We need a three-million-man march right now. We need Black men out on the streets like they used to be, talking to these young boys,” Ms. Smith said. “We need a Million Man March and a Million Woman March, or a unity march where women and men come together. I like to see our men in a positive role, and that was one of the most positive, encouraging things we’ve seen in a long time.”