The 20th century marked the first century of freedom for Black people in America in 400 years characterized by Black radicalism, nationalism, and visions of freedom. It could be said that dreams of unity and striking blows in the struggle for freedom and self-determination reached a mighty crescendo at the Million Man March on Washington, D.C.

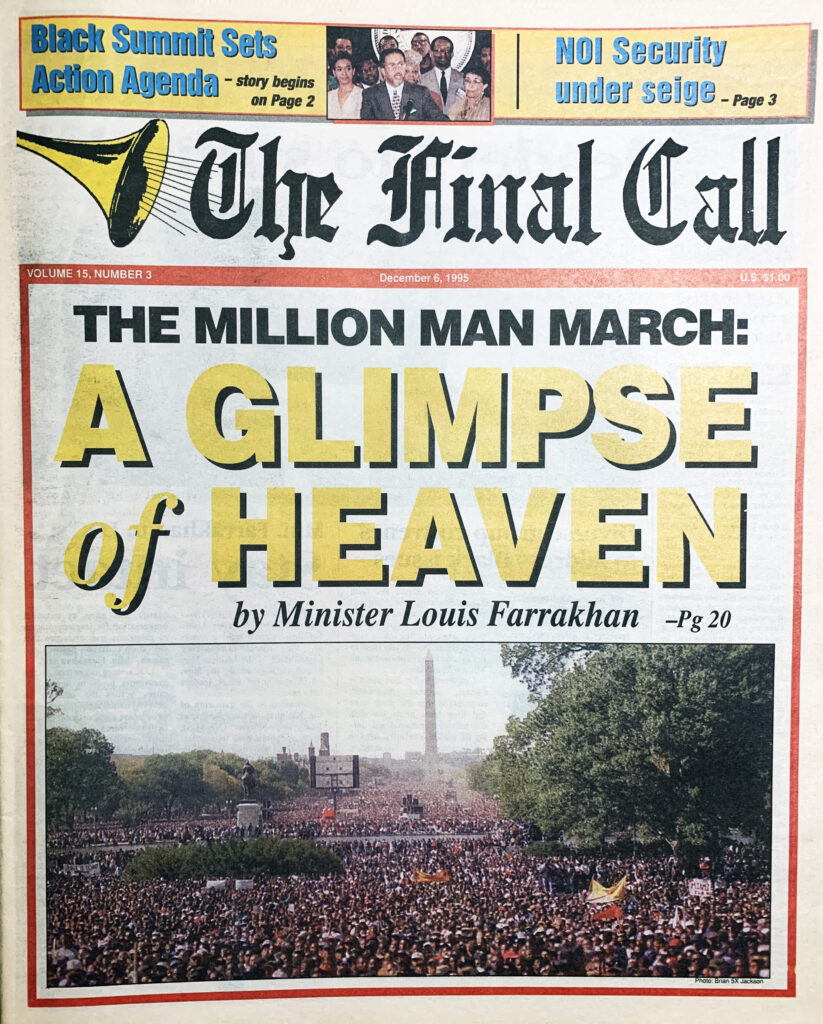

Despite what seemed like overwhelming opposition, political condemnation, fearmongering, anti-March organizing, insults, ridicule, media attacks and efforts to pit Black people and Black men and women against one another, the March overcame all naysayers and critics as Black men stood proud in the sun Oct. 16, 1995.

The March came shortly after the divisive and racially charged O.J. Simpson trial and the Black celebrity’s acquittal on charges he killed his White wife. Black men were increasing in the prison population. Black homicides through gang violence, drug turf wars were rising at an alarming rate. The conditions in Black America were worsening and many pointed to Black men as the problem.

The gathering shook the negative stereotype of Black men as a “Menace II Society.” It elevated the global image and work of Black men drawn to the call, vision and purpose of the March from its convenor, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam.

“The Million Man March was one of the most historic organizing and mobilizing events in the history of Black people in the United States,” accurately observed the late great Chicago-based activist Dr. Conrad Worrill. He served as longtime chairman for the National Black United Front and was a driving force with the organizing and mobilization of the October 16, 1995 Million Man March.

“The March was a divinely inspired gathering called by God through His servant among us, Min. Louis Farrakhan,” recounted Abdul Arif Muhammad, Nation of Islam general counsel.

At the time, he was the Mid-Atlantic Regional Minister for the Nation of Islam. “You have to understand the underlying spiritual motivation to understand the significance of the March. God called it through Min. Farrakhan. If you miss that point, you miss the whole point. It must be seen from that perspective. Why was it called? It wasn’t about jobs and justice; it was about men atoning to God. On that day, it was a call to God to seek His assistance and His help.”

Min. Arif Muhammad observed that the March had many antecedents. Min. Farrakhan initially made a call to Black men to “Stop the Killing” in the 1980s, he noted. “He came to understand there was a war planned against Libya, but it also had as a counterpart—the war against Black youth in America, the Black male,” Min. Arif Muhammad pointed out.

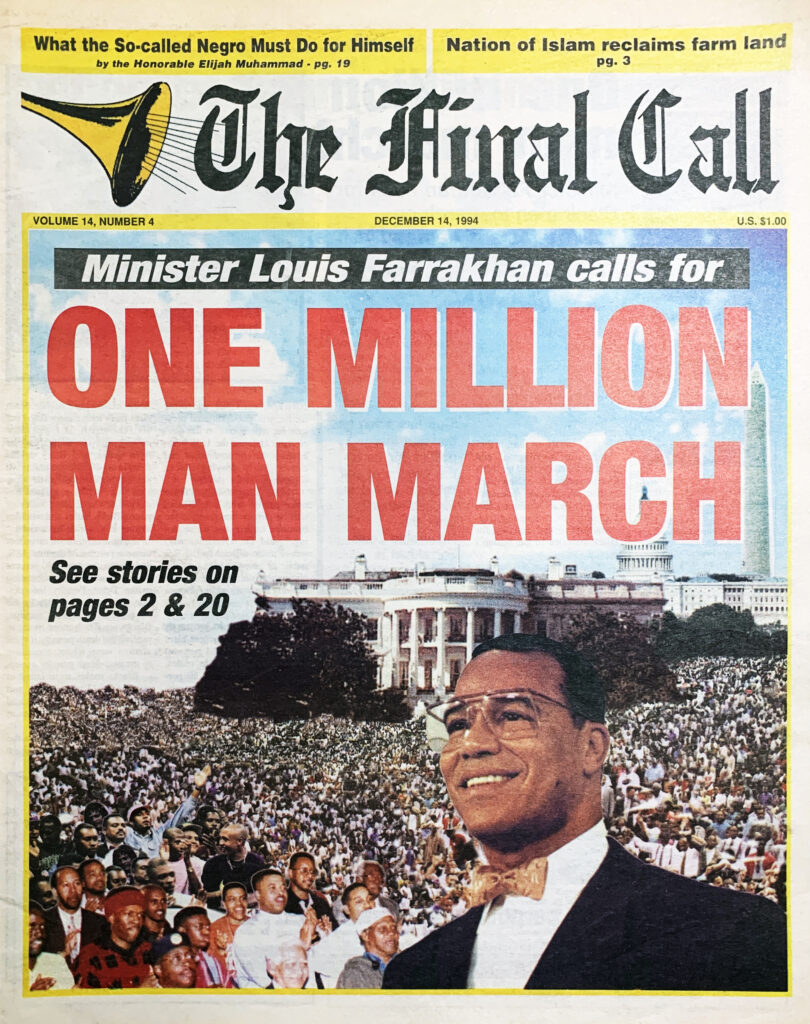

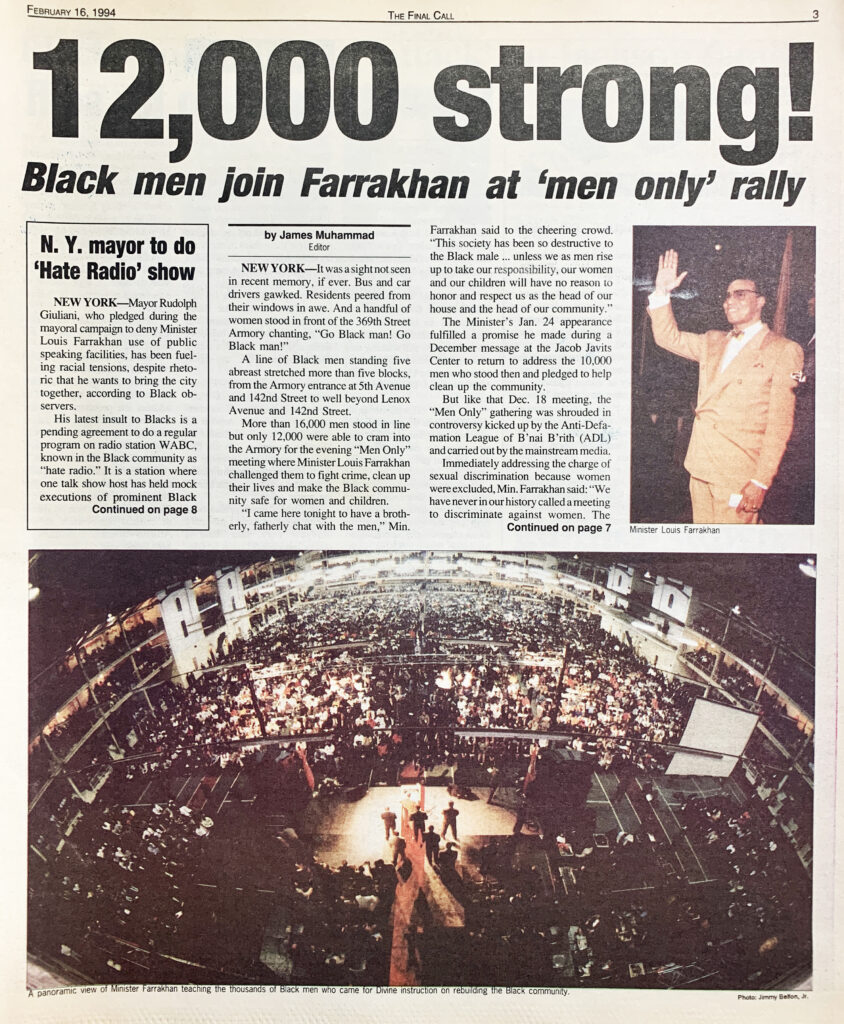

“Ultimately, those tours led to what became known as the Men Only meetings. Min. Farrakhan convened this first Men Only meeting at the 369th Armory in New York City on January 24, 1994. It launched the beginning of the “Let Us Make Man” tour, which became the springboard and catalyst for the historic 1995 Million Man March. He made the initial call for a million men to come to Washington, D.C., during that meeting,” Min. Arif Muhammad said.

“Over time, the vision for the call crystallized for him to ask Black men to atone for their sins, for not being the fathers, husbands that we should be as men and to atone to God for our failure. Also, the March was for us as men to take charge of our responsibilities in our communities and our families.”

Another critical aspect of the nuts and bolts organizational aspect of the March was establishing the Local Organizing Committees (LOC), Regional Organizing Committees (ROC) and National Organizing Committees (NOC) throughout the country. Min. Farrakhan crisscrossed the country meeting with community leaders, religious leaders, business leaders, activists and political leaders. Among those organizing, leading working and supporting the March were Maulana Karenga, founder of Kwanzaa and the organization Us; Haki Madhabuti of the Black Arts Movement and Third World Press; Dr. Benjamin Chavis, March national director; academic Dr. Cornel West; Dr. Conrad Worrill; and women like Dr. Dorothy Height, a civil rights legend; broadcaster Bev Smith; Atty. E. Faye Williams; Barbara Skinner, community and political activist; Cora Masters Barry, first lady of the District of Columbia; Mayor Marion Barry of Washington, D.C.; George Curry, of the NNPA Black Press of America; Rev. James Bevel, strategist for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; Leonard F. Muhammad, Claudette Marie Muhammad, Final Call editor James G. Muhammad, Supreme Captain Abdul Sharrieff Muhammad, Student Minister Ishmael Muhammad and Nation of Islam officials and ministers and Believers.

“He (Min. Farrakhan) would speak to the various civic, activist, community leadership and from that grouping of persons was formed the LOC. The group was created to work together in unity to help make the March successful all over the country,” explained Min. Arif Muhammad

Minneapolis-based activist Spike Moss, who served as National Cultural Affairs Director for the Million Man March, told The Final Call, “The March was the most remarkable thing I have ever participated in. I don’t know a greater time in our history that our people have come together on a positive note on behalf of their people under the call of one man called by God. I’m telling you that this was the greatest event in our history in America; the world thought we were down for the count when Min. Farrakhan called for the March, the world was able to see we were alive and well. We weren’t beat down or at the end of the road. Not only did we show up, but we also went home and did what he said to do.”

Mr. Moss said during his organizing of the historic National Urban Peace and Justice Summit to address fratricidal gang conflict and violence and promote peace he asked Minister Farrakhan to speak at the national summit in 1993. “I was having dinner with the Minister in Washington following my National Press Club announcement and asked him to speak at the summit,” Mr. Moss continued. “I knew he was the voice of our time. The problem with people today is their failure to recognize that voice. If you don’t open your eyes and ears, see and hear. It’s hard for people if your ego is in the way, if you are jealous and envious, you won’t recognize the greatness of that individual.”

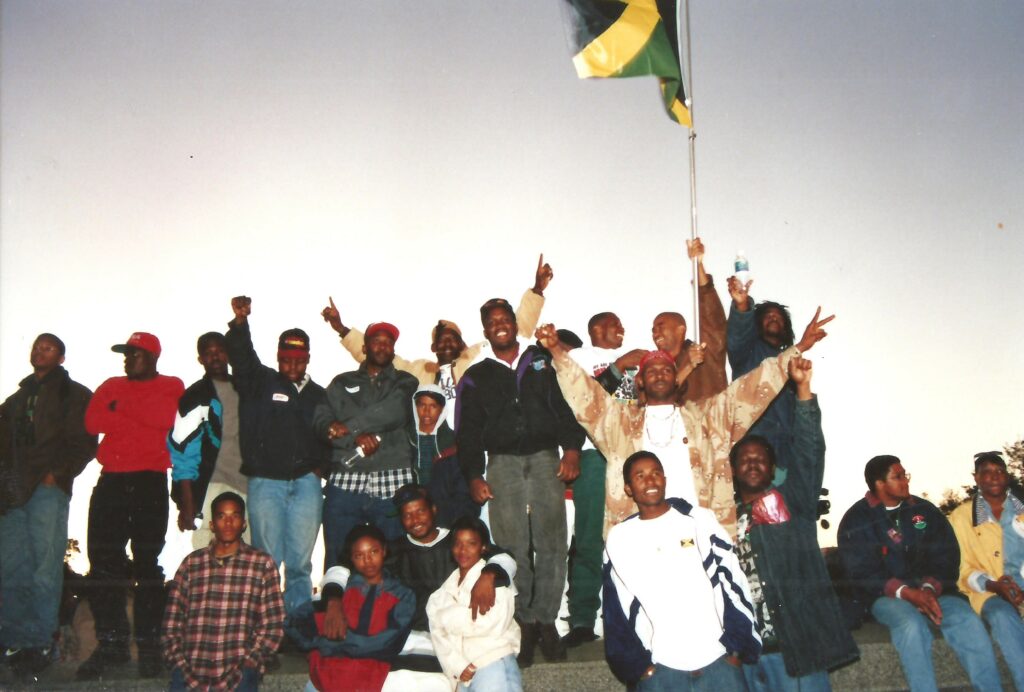

“You can criticize and say whatever you want; God blessed a man to call that many people to come in peace, and they all came on his voice. Only God could have blessed him to do it and then give him everything that he needed, including the vision and army of volunteers to make it happen,” said Mr. Moss, who remains an activist and advocate for young people. “On the way from Minnesota on the road running into lots of brothers and everyone asking, ‘are you on the way to the Million Man March?’ It brought tears to your eyes to see the brothers stepping out of all the buses and campers and running into each other. There was only one question, ‘are you on the way?’ ”

“It is particularly important that we not only remember it but do our very best to revise the spirit of the Million Man March when you consider we were able to do the impossible of bringing together all of the various segments of our community,” said the Rev. Willie Wilson. He was co-chair of the Washington, D.C. Local Organizing Committee. “We had professional associations, fraternities and sororities, Christian and religious denominations, other religions the Nation, orthodox Muslims, labor unions educators some of the mothers of the race, Dr. Dorothy Height, Rosa Parks, Maya Angelou. It was a miracle that once Brother Minister made the call, it was able to come together against stiff opposition.”

“My question is, why did God give us such a miracle? And my answer is He showed us that indeed above and beyond all of the religious differences, organizational differences that we can come together. Reviving that spirit is what we need at this time in our history in this country. We need to unify now more than ever, and I say the Million Man March showed us that it could be done,” added Rev. Wilson, who was also pastor of Union Temple Baptist Church at the time.

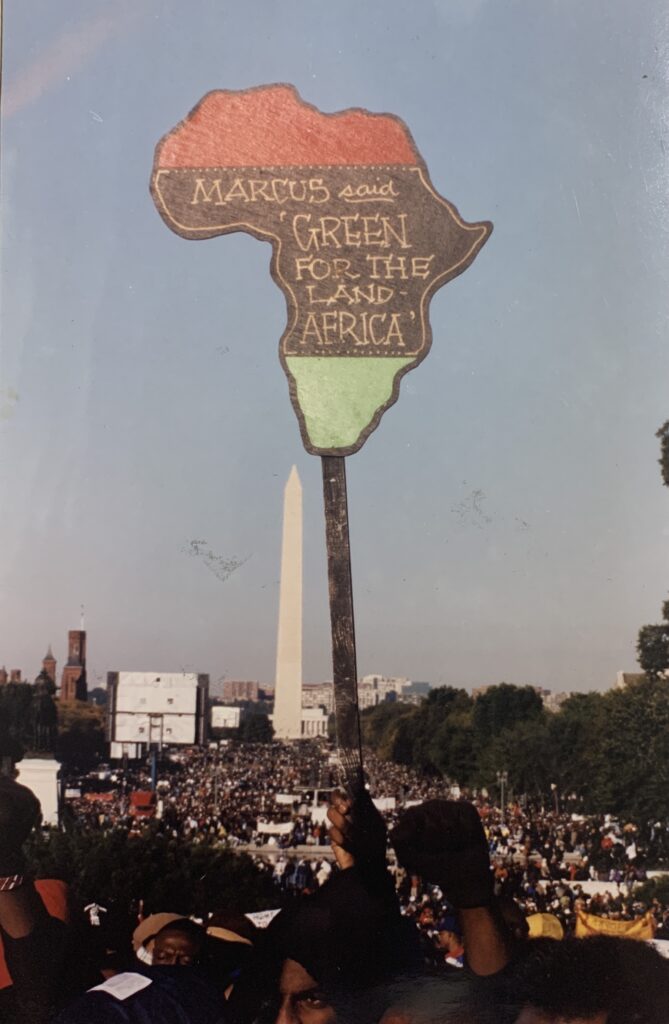

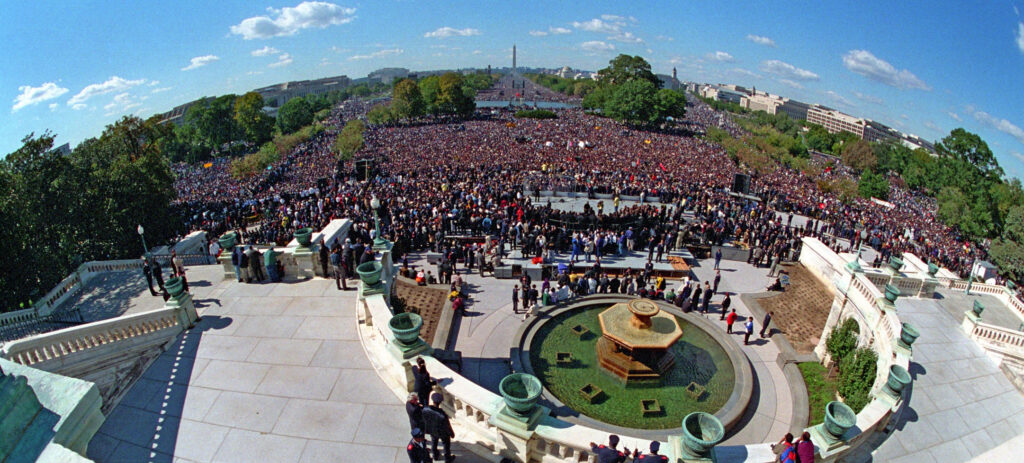

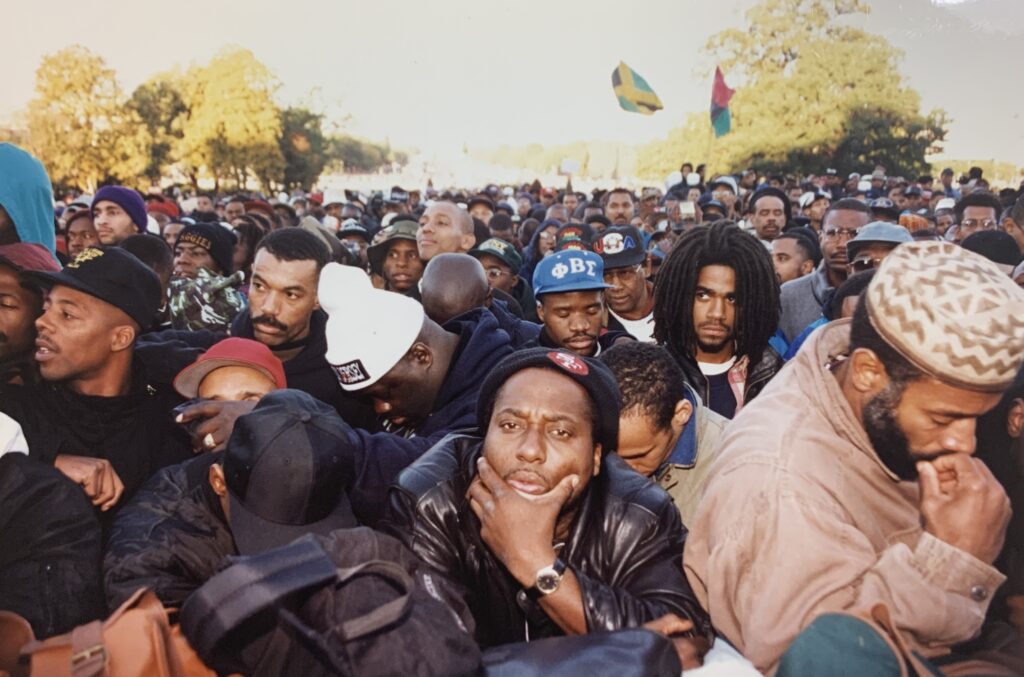

“On that day, Monday, October 16, 1995, there was a sea of Black men, many who stood for 10 hours or more sharing, learning, listening, fasting, hugging, crying, laughing, and praying. The day produced a spirit of brotherhood, love, and unity like never before experienced among Black men in America. All creeds and classes were present: Christians, Muslims, Hebrews, Agnostics, nationalists, Pan-Africanists, civil rights organizations, fraternal organizations, rich, poor, celebrities, and people from nearly every organization, profession, and walk of life were present. It was a day of atonement, reconciliation, and responsibility. More than a million Black men gathered in Washington, D.C., to declare their right to justice to atone for their failure as men and to accept responsibility as the family head,” said the official Nation of Islam website.

But it wasn’t a walk in the park. Downtown businesses were shuttered, Congress shutdown, President Clinton, who left town the day of the March, joined others in trying to “separate the message from the messenger,” and force rejection of Min. Farrakhan. Neither the NAACP, nor the National Urban League endorsed the March. Several other civil rights groups came on board weeks before the March happened, though their members and local chapters had already joined the effort.

There was also White fear about what could happen as the day of the March drew near. The level of organizing and mobilization leading up to the Million Man March was almost unbelievable said Abdul Sharrieff Muhammad, who was Supreme Captain of the Nation of Islam at the time. He spent six months in Washington, D.C. prior to the March working.

“We didn’t even get the permit until almost the last minute,” Min. Sharrieff Muhammad recalled.

“We had to meet with every level of law enforcement in the United States,” he said. “From police to military, they wanted us to know that the National Guard were deployed underground and were ready to deal with the crowd if things got out of hand.”

Not only were there no reports of violence at the Million Man March, or in the city, the National Mall was left as clean as the men cleaned up as they left.

A lawsuit was filed when the National Parks Service put March attendance at the ridicously low number of 400,000 people as the official count. A lawsuit from March organizers followed and Farouk El-Baz, director of the Center for Remote Sensing at Boston University, did a study that showed the March had drawn between a little less than 900,000 to 1.1 million people.

Organizing yesterday, lessons for today

Joseph Certaine was managing director of the city of Philadelphia and a vital member of the Philadelphia LOC.

“I think it is important that we recognize the 25th Anniversary. I think a lot was done to push the March from the memory of Black folks, and I think the mainstream media did it,” he said.

“I don’t think the Minister was ever recognized for the event that he mobilized and pulled off, and I really believe a lot of the brothers that attended have honored their pledge, but they haven’t done it publicly. I know that a lot of brothers who took the pledge meant it and have honored the pledge in the 25 years since that great event,” he said.

The Million Man March Pledge was a major part of the day. Repeating words first recited by the Minister, the men assembled thundered out a commitment to be better men, better husbands, community and world builders, peacekeepers and respecters of their women and all women.

“It was one of the most magnificent things to happen in the 20th century for these USA,” said Student Minister Rodney Muhammad of Philadelphia’s Mosque No. 12.

“The character of the March which was to not place demands on anyone but ourselves and not to hold expectations of any favorable outcome beyond ourselves and to present ourselves before our God. I think the character of the March escaped many people about why it was done and why it was done the way it was done,” he said.

The March was held on a Monday, participants were told to sacrifice to get there, not rely on others, to come unarmed, to come with a serious mind and to present their bodies as a willing sacrifice before God. They were to forego school, work and business to participate. Everyone had to give up something and Oct. 16 was declared a Holy Day of Atonement and Day of Absence—no school, no work, no sport, no play—from a society that had devalued and oppressed Black people. Though the March had an important social and political impacts, it was built on a spiritual foundation that called for a reconnection with God Himself.

“We were not marching because we were outraged, demanding something. Generally, our marches have been designed to go before White rulership to place a demand or level some request,” Minister Rodney Muhammad observed.

“And because none of these were involved, the March was more introspective. That was the beauty of the moment, and once we did it, people experienced something that they had never experienced. This March had a real impact on us looking at ourselves like men.”

He also followed the March outcomes closely: “1.7 million Black men registered to vote. Crime went down; within two weeks, 25,000 applications went in for Black adoptions according to the NABSW (National Association of Black Social Workers.)”

On Friday, Oct. 16, the 25th Anniversary will be celebrated, and its impact has not been lost nationwide.

Indeed, the commemoration started in earnest during the pandemic summer of 2020 in Columbia, S.C. Thousands gathered on Sunday, June 14, for a “Million Man March for Racial Justice.” It was a kind of reenactment of the original March. Participants were asked to come dressed in suits and ties, a style emblematic of the men of the Nation of Islam.

It was organized by ROAN Media Group (Rise of a Nation) member Leo Jones. He told The Final Call coverage of nationwide protests after the killing of George Floyd had, at times, shown Black men in a negative light.

It was time to shift the focus away from rioting and back to the message about justice as Mr. Floyd died in police custody as a Minneapolis police officer, who was later charged with murder, sat with his knee on the Black man’s neck for almost nine minutes.

“So we decided to use the Million Man March as a model to help change the narrative about how we were being perceived in the media,” Mr. Jones said. “We collaborated with the Nation of Islam here in Columbia and received their blessing. We wanted to show who the Black man is; we wanted to register folks to vote and ultimately spread the Black dollar’s importance amongst our community. So at the end of the March, where 4,000 people participated, we raised $10,000 and registered over1,500 people.”

A protest was held Oct. 3 in Annapolis, Md., to remember Black lives lost to police brutality and mark the 25th anniversary.

Community members seeking change stood as one. The message being sent home with them was simple. “To call on men once again to take their rightful role as leaders in the community to address the issues impacting our community,” organizer Carl Snowden of the Caucus of African American Leaders told the media.

All lives matter has been stated previously, but what’s happening is Black men and women are dying on the streets of America and the reason people have raised the issue Black Lives Matter is to remind America all Americans—regardless of their race, gender, nationality or religion—will be both respected and protected,” Mr. Snowden said.

In Boston, the Union of Minority Neighborhoods for Black Men’s Advocacy Day, State Rep. Bud Williams, and other partners are planning a day of inspiration, brotherhood, and agenda-setting through a virtual event.

“This year’s event will be in the spirit of the 25th Anniversary of the Million Man March and will be held on Wednesday, October 14 to recommit to making a difference in our communities, our families, and build fraternity amongst ourselves as Black men,” the group said.

Mathew Parker, who helped organize the event, was a teenager at the time of the original March. “We felt it was important to commemorate the March because if you don’t know where you have been, you won’t know where you are going,” Mr. Parker said. “I was 14 at the time of the March, and it had an impact on me through mentors and elders. Now we are at a time where we need strong Black men to stand together. I see the power in us being able to build and work together. The notion of accountability, brotherhood, and speaking for ourselves and the community—that spirit is essential.”

For the past 25 years, the Baltimore, Md., Local Organizing Committee has held a sunrise prayer service and breakfast to commemorate the historic March, said organizer Ertha Harris. This year’s event will be held on Oct. 16 in Druid Hill Park at 6 a.m. “Breakfast will take place at the Arch Social Club at 8 a.m.; then all men will meet and greet for dinner at the Garage 6 W Layette Street,” she said. “ ‘Men of the March: Before, During, & After,’ a documentary film commemorating the Million Man March, will also premiere on Oct. 16 at Art Social Club, 2426 Pennsylvania Ave. in Baltimore. Doors open at 8 a.m.,” she said.

Created and directed by AmenRa Darby of Black Nerds Production and Ms. Harris, one of the co-chairs of the Baltimore LOC, the film features members of the organizing committees, attendees and supporters dispelling the myths “tainting its legacy and reclaims the agenda of the March by sharing untold stories about their lives before the March, during, and after.”

The annual sunrise prayer honors sunrise on Oct. 16, 1995, as “God revealed the majesty of one million Black men coming together in unity and harmony,” said Ms. Harris.

Ron Moten of Don’t Mute DC plans to use Oct. 16 to “Crank the Vote,” through collaboration with go-go artists and mark the 25th Anniversary of the Million Man March with the Backyard Band performing on a flatbed truck. “The music is high energy and provocative, so it keeps the people engaged in the protest,” Justin “Yaddiya” Johnson told a D.C. alternative newspaper. His “Long Live GoGo” has organized mobile musical protests. The event begins at D.C.’s Howard Theatre and ends at Black Lives Matter Plaza downtown. “Crank the Vote is educating Black people why they must get out and vote and hold elected officials accountable,” Mr. Moten said. “It’s time for America to atone for its treatment of Black people.”

In Kansas, The Topeka Capital-Journal reported, “Farrakhan’s mission for the Million Man March was clear: he sought to promote community, unity, and family values among African Americans. That historic March was the inspiration for an event being held in Topeka on October 17, just one day after the 25th Anniversary of the Million Man March.”

“The local event is being organized by Topekan Lisa Davis. Since she couldn’t hold it exactly on the March’s 25th Anniversary, she is calling the event ‘Spirit of the Million Man March.’ Ms. Davis has partnered with the NAACP Youth & College Division, IBSA Inc., New Mount Zion Baptist Church, Black MentoUrs, and Topeka Family & Friends Juneteenth Celebration to put on the Spirit of the Million Man March. The event will take place from noon to 3 p.m. on October 17.”

Min. Arif Muhammad stressed that the March was based on atonement and reconciliation and the Million Man March Pledge and should not be forgotten. “Remember the men were asked to take a pledge, so the pledge lives going foreword, that pledge is still alive today. Now we must redouble our efforts,” he said. “That day was declared a Holy Day. The pledge was action items for us to commit to benefit our community. Of course, the eight steps of atonement came from Rev. James Bevel. He brought the theme of atonement for the March. So, these are the critical action plans that came from the March, and they still resonate today.”

“The March showed that Black people could get together. The March took us to a whole new level,” said Dr. Ray Winbush, a Morgan State University professor. “It showed we could raise our own money; we can do for self. Unity is the primary thing that we need to do now, and the MMM showed us we could do it.”

“I was in Nashville at the time the call was initially made. People scoffed at the idea that one million Black men could get together. They thought it was impossible and insane. We can organize a whole world of Black men to do anything that we want to do. It is now more important than ever, and hopefully, with us looking at the echo of the Million Man March, it will rekindle that thinking for the current and new generations,” Prof. Winbush added.

(J.A. Salaam and Final Call staff contributed to this report.)