When it comes to appreciating the power of African artists and their historical impact on geopolitics there is no shortage of icons from which to choose.

A recent documentary produced by France24 focusing on the legacy of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie is a case in point. His historic 1963 speech to the United Nations General Assembly inspired reggae legend Bob Marley—a son of Africa by way of Jamaica—to write his classic, anti-colonial, anti-racism, human rights classic appropriately named, “War.” The song was taken word-for-word from the Ethiopian leader’s UN address.

Marley set Salassie’s speech to music, similar to hip-hop artists and their history of sampling excerpts of speeches from Black leaders like Minister Louis Farrakhan and Malcolm X.

According the book “A Brief History of Seven Killings” by Marlon James, Bob Marley sings the words of Haile Selassie over a steady reggae beat by Aston “Family Man” Barrett, his brother Carlton, and the other members of the Wailers.

Roots reggae traditionally has short, punchy refrains but this song by Marley draws its mounting tension from Selassie’s extended rhetorical complex sentences, release and relief coming only with the refrain of the word “war.”

Excerpts of the song:

Until the philosophy

Which hold one race superior and another

Inferior

Is finally

And permanently

Discredited

And abandoned

Everywhere is war

That until there is no longer

First class and second class citizens of any nation

Until the color of a man’s skin

Is of no more significant than the color of his eyes

Me say war

That until the basic human rights

Are equally guaranteed to all

Without regard to race

Dis a war

That until that day

The dream of lasting peace,

World citizenship

Rule of international morality

Will remain in but a fleeting illusion to be pursued,

But never attained

Now everywhere is war

War…

In 1993 Min. Farrakhan explained the importance of a country having a measurable standard for what is right. That sentiment is still applicable today. According to the Minister—an accomplished violinist and former Calypso singer, who in 2018 put out a limited-edition music box set called “Let’s Change The World,” featuring seven CD’s with over 40 songs— artists have historically contributed to the mental, moral and “spiritual wellbeing” of society. Min. Farrakhan emphasized the importance of artists recommitting themselves and returning to their “responsibility.”

“To be the voice of a nation speaking to the wider world is a tough mission for any performer,” wrote Jon Pareles in response to the 2008 passing of South African singer Miriam Makeba. Referred to as “Mamma Africa” she had “an activist’s tenacity and a musician’s ear,” he wrote.

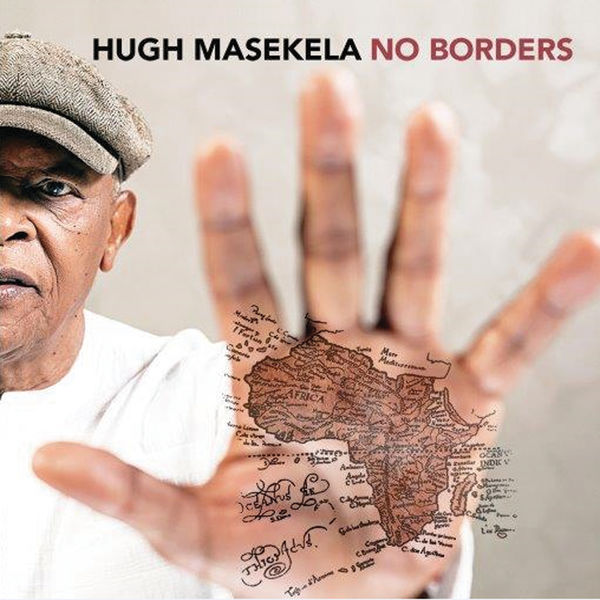

Makeba was previously married to civil rights icon Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) who popularized the phrase “Black Power” and also to South African musician Hugh Masekela. She said: “I am not a politician, but I am a South African who feels and who knows where I come from and what we are going through. And I said I don’t sing politics, I sing – I merely sing the truth.”

Roxanne Lawson, who in 2008 was TransAfrica’s director of Africa Policy, while being interviewed about the passing of Ms. Makeba described that for her organization the merger, love and marriage between activism and art fueled much of their work. “And as someone who grew up in the anti-Apartheid struggles, I remember as a child listening to her and then hearing her and seeing her play a role in ‘Sarafina’ not realizing who she had been,” she added.

“Then as I grew up, realizing what she had given to me as someone who grew up in the United States the ability to live life on your own terms, to honor your culture through music and expression and to be yourself.”

In a study focusing on the influence of music on the anti-apartheid movement, titled, “The Beat that Beat Apartheid,” Ann Schumann described this form of music as a “tool” for conflict transformation by connecting and uniting diverse groups of people, raising awareness, sharing narratives about concerns, revealing identities, fighting back against injustice and influencing social movements.

No single artist perhaps represented this form of consciousness raising protest music more than South African musician Hugh Masekela. No song represented the plight of the suffering southern and central African worker more than Masekela’s song “Stimula (The Coal Train).” In the book, “Soweto Blues,” Gwen Ansell writes that Masekela’s lyrics acknowledges a train coming from various southern and central African countries. The train carries “young and old,” Masekela says before beginning to sing: “African men who are conscripted to come and work on contract in the golden mineral mines of Johannesburg.” He describes how the men sit in “stinking, funky, filthy, flea-ridden barracks and hostels” and that they work for 16 hours “for almost no pay—and “deep down in the belly of the Earth.”

In the song, “Been Such A Long Time Gone,” motivated by his exile from his beloved South Africa for speaking out against the apartheid regime, Masekela tells the story of a journey from exile back to the African continent. It takes him to the Sahara Desert, the Nile River and the Zambezi River. He eventually comes to White South African soldiers standing in the road, as he tries to return home. They open fire, and then, “Pop! goes my dream,” he says. The title song of the album containing the song is “I Am Not Afraid.” The album cover features a photo of Masekela with his head under the raised foot of an elephant.

Talk about a rebel with a cause, Nigerian musician Fela Anikulapo Kuti expressed music with an explosive African beat. Fela once said, “You cannot sing African music in proper English.” Fela is the “Afro-beat savant” and a musical genius. He was influenced by Black America’s activist struggles and African American music, in what could be interpreted as an African response to the Nation of Islam lesson which asks the question: “Who is the original man?” Fela sings: “I no be gentleman (white man) at all o/I be African man original.”

Fela’s concerts, part jazz, part funk, with five saxophones, three percussions, a drummer, and four singers were conjured up a throbbing, enchanting pulse, author Frank Tenaille writes in his book, “Music is the weapon of the future,” written in the year 2000. A canvas of basses woven with percussion threads and brass riffs served as a backdrop to the lead saxophone, the chorus, and the psalm-like change that makes Fela’s lengthy pieces so unique.

With jabbing words and acid themes, his songs (such as “International Thief Thief”) explicitly denounce neocolonialism and the control of the African economy by multinational corporations, especially in Nigeria and other countries in the Motherland. —Follow @JehronMuhammad on Twitter