Lucien Neal started his day by giving each of his four pet rats a kiss. Later that morning, he walked downstairs holding his giant flower bowl with headphones on. He was laughing at memes on his phone and eating his cereal when his mother touched his shoulders.

“He looked at me and paused what he was looking at. I’m like, ‘If anyone ever puts their hands on you, if it’s a person of authority, don’t tense up. I don’t know what you can do because most likely they’ll still kill you, but just try to come home to me,’ ” DeShanna Neal told her 15-year-old son.

He asked her, “What happened?”

She had to explain to him what happened to Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old Black man who died in Aurora, Colorado, last August after being reported as suspicious. Police approached him, held him in a chokehold, causing him to be unable to breathe and to vomit. When paramedics arrived on scene, they injected him with ketamine. He later went into cardiac arrest and died after being declared brain dead.

After hearing what happened, Ms. Neal’s son told her, “It’s not even just racism anymore, mom. I think they just want to see us as dead bodies.”

“And he’s like it’s pretty much slavery. If we’re not enslaved, we need to be dead,” she said. “And that hurts. You don’t want your 15-year-old child to see the world that way. He shouldn’t be that jaded already.”

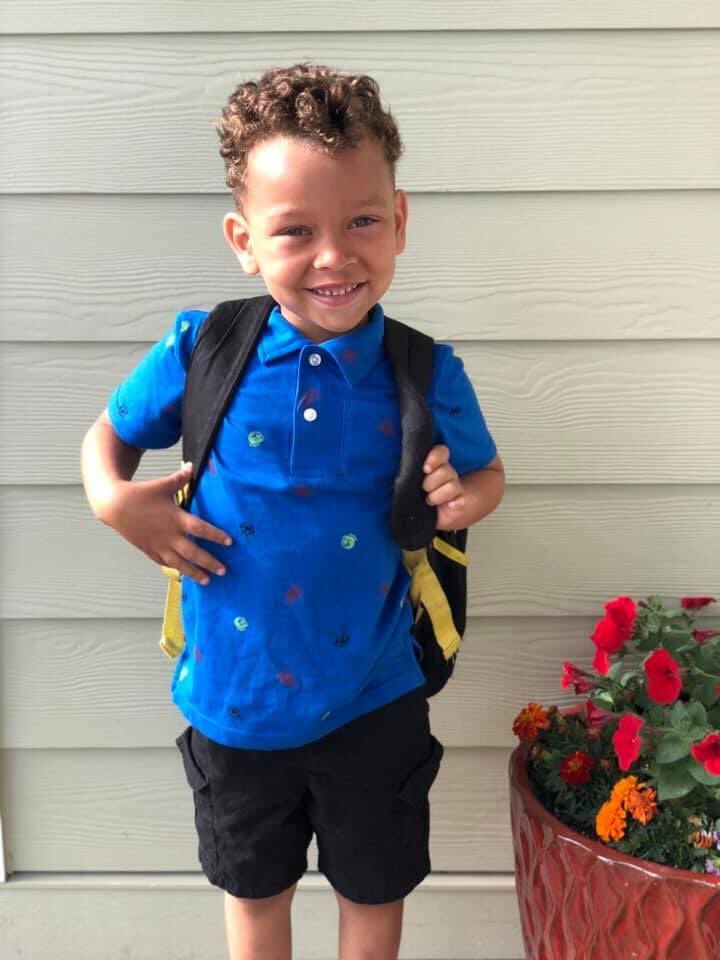

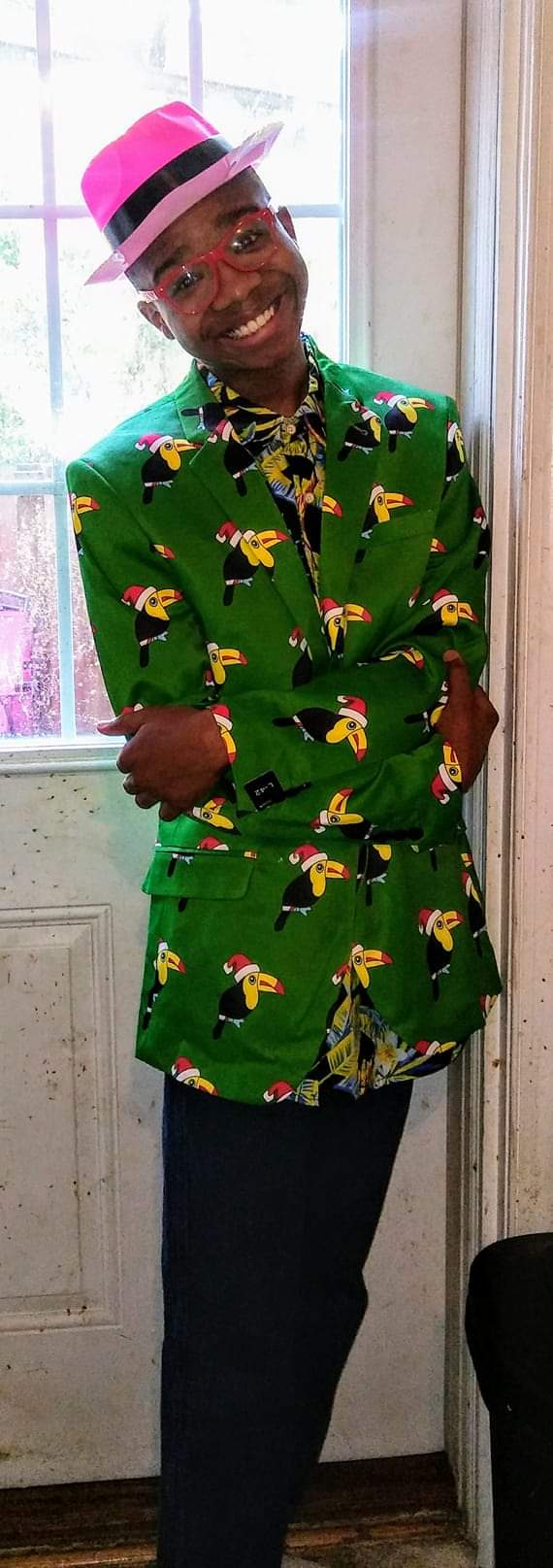

Lucien Neal has ADHD. He’s 6 feet tall. His mother describes him as goofy and sweet. He’s an honor roll student, and his teachers love him.

Lucien Neal plays the cello. Elijah McClain taught himself to play the guitar and the violin. The Neal family’s three cats like to sit and listen to Lucien play the cello. Elijah McClain would spend lunch breaks at local animal shelters to put on concerts for dogs and cats. Elijah dances similar to Lucien: terrible, said Ms. Neal. The two have a similar smile. Even Elijah’s final words, saying that he was different, that he’s introverted and asking police to please respect his boundaries were words Ms. Neal could hear her son saying.

“That poor, poor, beautiful son. He wasn’t even doing anything. I literally saw my son just walking. They have the same walk!” she said. “I saw my son. And truly, I felt like I was watching my son be murdered in front of my eyes, and I know I was watching somebody’s son be murdered.”

Elijah McClain’s death has sparked parents and family members to have conversations on the reality of their autistic and intellectually disabled children and young adults. Many took to social media.

Actress Sherri Shepherd posted in an Instagram caption, “I am a mother of a black boy. As I kiss my son goodnight, I cry with anguish in my soul. Because soon Jeffrey, who loves the WWE and making people laugh will be out walking wearing his hoodie, (bc it calms his nervous system). What will people think or do to my Baby just bc his skin is brown?”

Actress Holly Robinson Peete, mother of an autistic son, also took to Instagram to share Elijah McClain’s story.

“You can see and hear the innocence, quirkiness and sweetness in his voice. He’s clearly a young man who has a pure soul—much like my RJ —and can’t understand why people would want to hurt him!! Why are cops so tone deaf to this type of human being? … This is not about good cops versus bad cops; this is about right versus wrong. It’s about a mom like me not panicking every single time my kids leave the front door.

“It’s hurts so deeply because that could’ve been my son. If it couldn’t have been yours why does my son’s life matter less???”

When Shannon Van Hook from Chehalis, Wash., saw Elijah’s story, she started sobbing.

“When he asked to please respect my space and my boundaries, it’s something that we tell Lincoln to say, too, when he’s uncomfortable, so that people know to please not touch him. I read his last words, and the last things he said were very much like the way that Lincoln speaks, where it seems random, but with kids who struggle with social issues or who are on the spectrum, it’s not random,” she said. “He was trying to connect to those officers, which is why he told them he loved them. He wasn’t judging them. He was trying to find this connection. That’s why he said so many different things.”

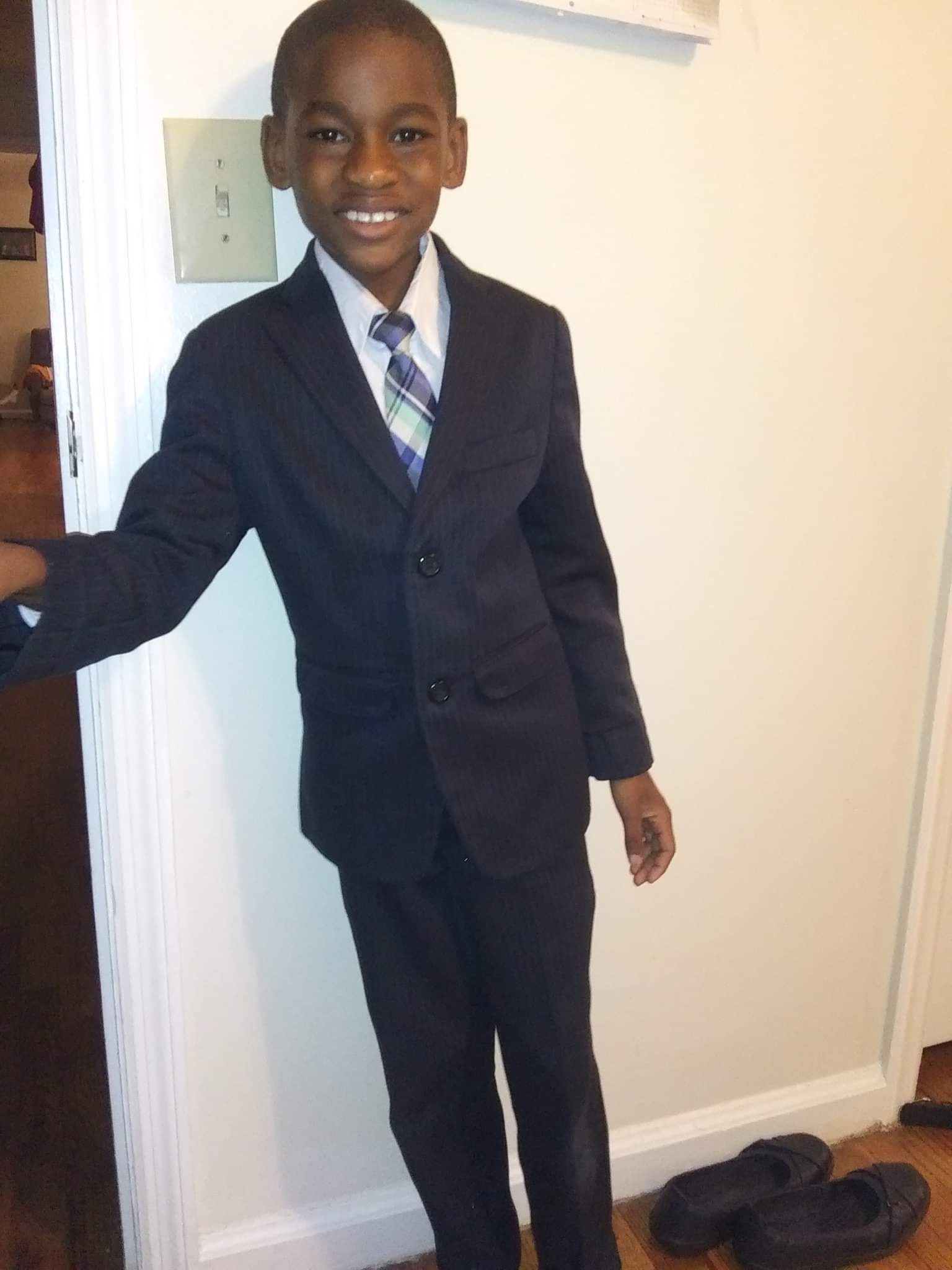

Ms. Hook’s six-year-old son, Lincoln, was diagnosed as gifted, with an IQ ranging above 130, and he has high-functioning autism. Ms. Hook said he has a high level of stranger fear. Though he has issues with connecting to people socially, he’s outgoing and is always smiling.

Before Covid-19 shutdowns, Lincoln would have meltdowns in school because of his sensitivity to lights and noise.

“All of that bothered him. It sends him into a sensory overload, and so he ends up having a meltdown, which looks like a tantrum. Lincoln was subsequently deemed by this school to be a threat. My six-year-old Black, 43-pound son was deemed to be a threat and was held in a closet with the door shut. They don’t know how to deal with children like that,” Ms. Hook said.

She has been communicating with her congressmen to get a medical designation for drivers who are on the autism spectrum.

“When they run the plates, I want it to pop up that the driver is autistic before they approach, because when they’re approaching, you’ve seen it in the case of Elijah. People thought he was on drugs,” she said.

She also wants a medical designation on driver’s licenses of people with autism.

Anwar Muhammad from Macon, Georgia, who has a 10-year-old autistic son, doesn’t believe the police in Elijah McClain’s case failed to recognize the signs that he was different.

“He pulled down his mask and he communicated. You could’ve actually seen that he probably either had some type of delay or some type of connection with the autism spectrum,” he said. “I just don’t believe that these police officers came across this individual and didn’t see any signs of limitations. They just ignored it. That’s what I feel.”

His 10-year-old son, Siddiq, is very energetic. Mr. Muhammad said he loves to play and is very active, but he also loves to be alone. Siddiq’s “stim,” which is a repetitive movement or sound that children on the autism spectrum display, is clapping.

“There’s usually something with speech, or there’s something with constantly doing something with your hands. There’s some type of motion,” Mr. Muhammad said. “It would only take you a minute or two [to see] that somebody has special needs. It’s not difficult.”

His son isn’t at the level, yet, to have the conversation about what to do in a police encounter, but Jeanyves Cordier out of the Hartford, Conn., area has had the conversation with her 21-year-old autistic son, Brandon, since he was 10.

“In the beginning, it was always say ‘yes sir’ or ‘yes ma’am.’ Always do whatever they ask you to do. Put your hand on the dashboard if you get pulled over. It was always that manner of teaching,” she said.

After everything happening recently, especially with the deaths of 46-year-old George Floyd, who died in Minneapolis, Minnesota, after an officer used a knee chokehold technique. And 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery, who was shot and killed by two White men in Glynn County, Georgia, her son came to her.

“All these years you told me to do X, Y and Z, and even that doesn’t help because even then, they did everything that you always told me to do and they still got murdered,” he told her.

She described Brandon as the average young man who loves video games, loves his family and loves to joke around. He’s very quiet, and he’s intelligent. But she thought of him when she saw what happened to Elijah McClain.

“Honestly, I’m at a loss, and that’s why after these particular murders this year, I broke down because I don’t know what to say to him anymore,” Ms. Cordier said. “I told him all the things we’re supposed to tell them. Do what you’re told, do this. Now I’m at this point where I just feel like saying, you know what? Once darkness comes, stay home.”

Jackie Pilgrim from Durham, N.C., and her 20-year-old autistic son, Hunter, are active with their local Crisis Intervention Team (CIT), which is a group of people who train first responders on the best way to interact with people who either have a mental illness, autism, an intellectual disability or someone who may be struggling with substance use.

Hunter is on the severe end of the spectrum and is nonverbal. His mother describes him as having one of the most humble and genuine personalities. She said he’s a helper by nature, he’s very compassionate, and he picks up if someone is struggling with something emotionally. She gave an example of when the two of them were in the self-checkout area of a grocery store once, and her son walked away from her.

“I didn’t know that he had picked up on someone having some issues or feeling depressed. And when I looked up, my son was standing next to the woman at the cashier and holding her hand and she was crying,” she said. “She’s crying profusely, and she can’t even get her words together. I had to give her time. And once she was able to speak, she said my son’s spirit was the most pure spirit she’s ever felt and that he must have picked up on the fact that she had some very heavy concerns.”

Ms. Pilgrim founded the organization Autism’s Love: The Pilgrimage, where she works with parents whose children are diagnosed with autism. She is also a part of many other organizations geared around disability and mental health, including the National Black Disability Coalition, which was founded in 1990 in response to the need for Black disabled people to organize around mutual concerns.

A part of her CIT demonstration included teaching police officers and first responders that signs of autism may not be obvious right away.

“I would have my son, who would be sitting in front of the officers and first responders, and the traits that he was presenting, it was clear that there was an intellectual disability present,” she said. “But I would stand in front of him, and I would put a baseball cap on him, sunglasses, give him a lollipop and then I would step back and I would say, ‘Do you see disability now?’ ”

When they said no, she urged them to start taking a few extra moments to be able to communicate effectively. But even with all the training she does with officers, she still questions if it’s enough, especially when she heard Elijah McClain’s story.

“I struggle with the notion is it going to make a difference for my son or any son, and what if it was my son? I don’t think I have the vocabulary to be able to express how devastating this is to me,” she said over the phone, in tears.

Mr. Muhammad is on board with the idea of having national training for police to recognize people who are disabled.

“I think that type of training is needed, not just in the police profession. I think that training is needed in all levels of government, municipalities, so that you can have a sensitivity level to say ok, this person, I’m giving them commands. They’re not responding. Maybe they might be on the autistic spectrum, or maybe they might have a mental illness. Ok, let me try this from my training,” he said.

Ms. Cordier said defunding the police is a cause she believes in.

“Use some of the funding that they’ve received to train the police officers … in de-escalation. Train them more, or even use some of that funding to hire mental health workers to go along with the police officers during a particular type of call,” she said.

She said children like her son shouldn’t have to worry about what happens if they step outside.

“A lot of our kids are really good, down-to-earth kids who just want to live,” she said.

Ms. Neal has been outspoken about how White children with autism receive all hands on deck while Black children don’t receive that same level of attention.

“Black people are not allowed to be disabled. We’re not allowed to be able-bodied. We’re not allowed to be,” she said.

She said Black children with disabilities should be respected and given the same resources and services as any other child with those same disabilities.

Ms. Hook said she has hope for training and that she doesn’t want to see another case like Elijah McClain.

“Our kids, they’re not mentally ill. They’re not mentally deranged,” she said. “They’re gifted, they’re geniuses, they’re special. And they’re just different.”

The one-year anniversary of the death of Elijah McCain is August 24.

(Anwar Muhammad is related to Final Call contributor Anisah Muhammad, who wrote this article.)