Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in the United States early in 2020, public reaction has ranged from alarm to indifference to fear.

Prison reform advocates, family members of those who are incarcerated and others have been sounding the alarm about the largely silent but unchecked spread of the disease in prison, jails and detention centers.

Prisons have been described as “petri dishes” and “incubators” where the deadly pandemic is allowed to flourish and spread easily throughout prison populations, corrections staff and others who work or come in contact with those behind bars.

According to data tallied by the Justice Roundtable, at least 84,000 people in prisons and jails have been infected and at least 703 incarcerated individuals and corrections workers have died from the virus, said human rights attorney Nkechi Taifa.

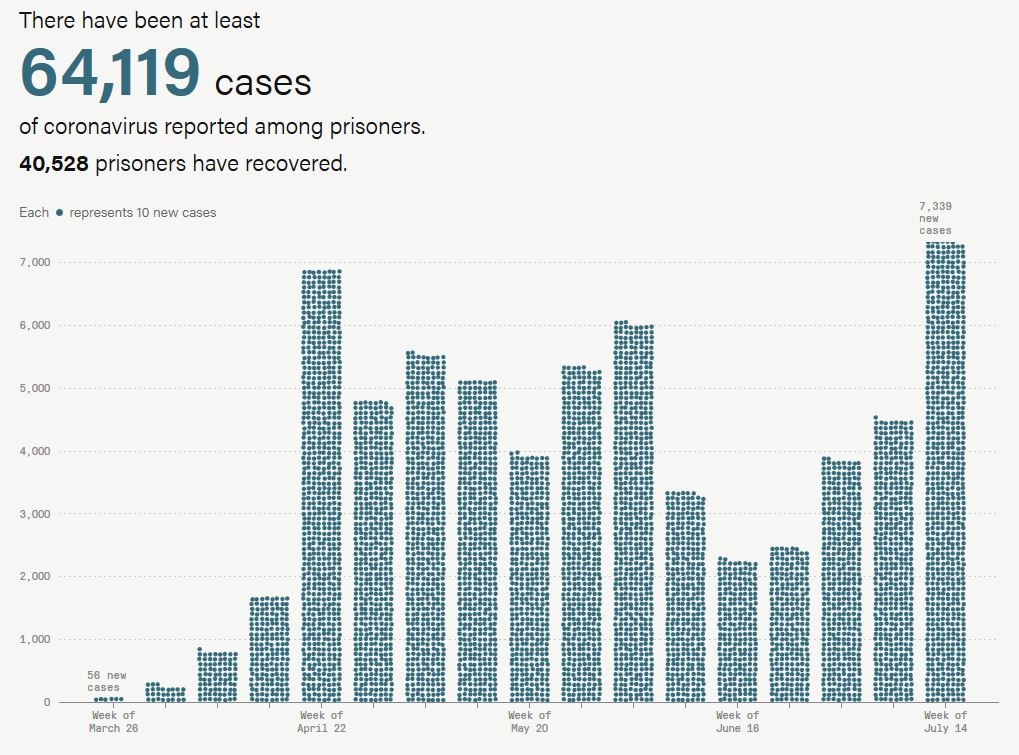

The Marshall project chart 01

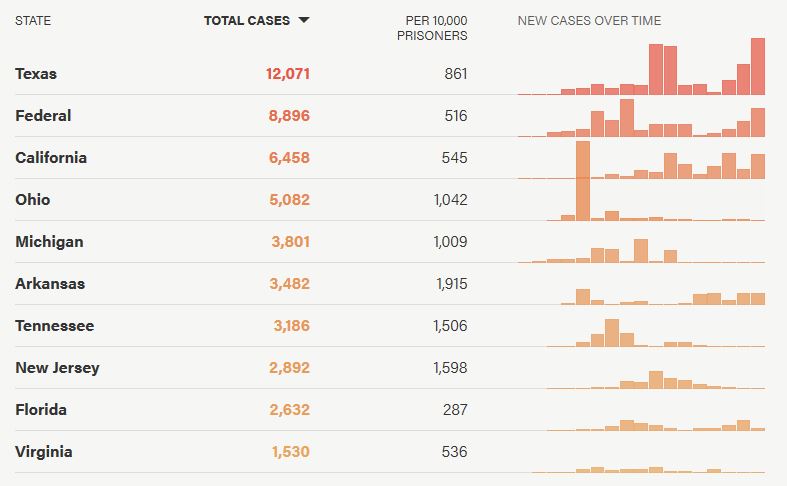

The Marshall project chart 02

The Marshall Project reported that by July 14, at least 64,119 people in prison had tested positive for the illness, a 13 percent increase from the week before. “The growth was driven by big jumps in prisoners testing positive in Texas, California and the federal Bureau of Prisons as well as outbreaks in Idaho, Iowa, Oregon and South Carolina,” said the Marshall Project, which reports on conditions and news related to prisons, jails and those behind bars.

In one federal prison in Texas, just over 500 women were reported Covid-19 positive, said July 21 media reports. “That’s nearly 40 percent of the detainees,” CNN said. Three guards were also reported ill.

In Florida, an epicenter for the pandemic, there were complaints officials were doing far too little with corrections officers and inmates getting sick. A Tampa newspaper said, “Of the 24,000 prison staff who work across the state, 1,182 have tested positive for the novel coronavirus” by the third week in July.

More than 1,000 of the 1,798 incarcerated individuals tested positive for coronavirus at the Federal Correctional Institute in Seagoville, Texas, and one person died, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Texas’ numbers reflect the explosion of Covid-19, with a staggering 300,000 confirmed cases.

Ms. Taifa, a criminal justice reform advocate, reiterated her deep concern that Covid-19 poses a deadly threat. Covid-19 is a timebomb and if prison authorities, elected leaders and others with the power to implement adequate safety measures don’t do so, everyone is in danger, she warned.

“The spread of Covid-19 inside of U.S. prisons, jails and detention centers must be stopped if society as a whole is to be safe,” said Ms. Taifa, founder and convenor of the Justice Roundtable, a broad-based coalition of more than 100 organizations working to reform federal criminal justice laws and policies. “Nine of the 10 largest known clusters of Covid-19 infections in the United States are in correctional facilities … these institutions are incubators for the virus. Social distancing is nearly impossible, and incarcerated populations are at greater risk for health conditions that suppress immune response. Moreover, due to the harsh and lengthy sentencing policies over the past three decades, many are elderly with increased vulnerability to the virus.”

ddie Conway described what’s happening in U.S. prison in apocalyptic terms. “All of these jails are concentration camps, and coronavirus, which is spreading in Rikers (a New York state prison), makes it a death camp,” said Mr. Conway, a former Black Panther Party member and rights advocate. “They (prison officials) need to do something so people can protect themselves. There’s gonna be a humanitarian disaster of genocidal proportions. There are 2.3 million people in prison in the United States, 75 percent of them are people of color.”

Mr. Conway, who spent 44 years behind bars after conviction for a murder he has always denied, warned the coronavirus “is rocking the U.S.,” and “expanding exponentially.”

“They need to give them hand sanitizers. Officials declare it as contraband, but it should be available in certain allotments, even one little medicine cup after a meal,” said Mr. Conway, an author and host of The Real News Networks’ “Rattling the Bars.” “They need to let out at-risk people, give hazardous pay to cooks, those who mop floors, clean up and pick up trash,” he said.

“What people are asking for but it’s not listened to here is the release of Everest prisoners—those who’re old and sick. They could wear ankle monitors.”

Prison and jail guards are constantly coming back into the community when they leave work each day, thus jeopardizing those in communities outside incarceration centers, Mr. Conway explained.

When officials from the Department of Homeland Security, the Bureau of Prisons and ICE testified at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in June, they acknowledged the uneven nature of their response to the pandemic and promised a more effective program, but that, so far, has proven to be elusive.

Reform Minister for the Nation of Islam

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) told panelists and fellow senators during the June 2 hearing that the public health crisis that now grips the nation’s prisons and detention centers was avoidable. He said he and more than a dozen senators sent a letter to Attorney General William Barr asking him to move quickly to blunt the spread of Covid-19.

“On Dec, 2018, First Step Act gave BOP the authority to quickly release or transfer vulnerable inmates to home confinement,” said Sen. Durbin, the second-highest ranking Democrat in the Senate.

“We see the reports every single day. But listen to this number: the rate of infection is 6.6 times higher than the general population of the United States,” he added.

The federal Bureau of Prisons reported July 17 that there were 3,591 federal inmates and 315 prison staff who tested positive for Covid-19 nationwide. Currently, 5,434 inmates and 631 staff have recovered. Meanwhile, 97 people in federal prison and one prison staff member has also died from the disease. There are 129,268 federal inmates in Bureau of Prisons-managed institutions and 13,895 in community-based facilities. Their staff is approximately 36,000 people.

Abdullah Muhammad, National Prison Reform Minister for the Nation of Islam, has been serving those locked behind bars for some 30 years. The Covid-19 pandemic has meant no visits or religious services at federal prisons, state prisons or county jails.

“Some feel they were treated unjustly, kept for long periods of time in uncomfortable places away from the comfort of their dorms for extensive periods of time,” said Min. Muhammad.

They also complain that if an inmate tests positive, prison officials will lock down an entire cellblock and place everyone on quarantine for long periods of time, he added.

At one facility, inmates let him know about their plight and Min. Abdullah said he was able to talk to a chaplain and he was able to help get some restrictions lifted.

Curbing this deadly virus is “overwhelming,” he said.

“Many inmates are also grieved because funeral visits are suspended and many of them are losing loved ones by the numbers and they cannot visit them. That’s one of the greatest hardships they are going through. One NOI brother lost his father and said he cried like a baby and he could not visit for the funeral,” Min. Muhammad added.

He has been able to get a letter of encouragement distributed to some inmates encouraging them to study the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam. Chaplains in some institutions have also agreed to allow inmates to view Min. Farrakhan’s DVDs on their institutional channels, said Min. Muhammad.

Barbara Bradley Hagerty, a contributing writer at The Atlantic, notes in her article entitled, “Releasing People From Prison Is Easier Said Than Done,” that as the pandemic threatens the lives of those behind bars, the country must confront a system that has never had rehabilitation as its priority.

Inmates “are trapped as the virus spreads, effectively turning their prison sentences into death sentences,” she wrote. “How do we stem the wave of infections? The answer, according to many advocates, is simple: Release prisoners.”

But she and others like Color of Change’s Scott Roberts and Nicole Porter of the Sentencing Project point out that elected officials are making a political decision about whether to release people behind bars and trying to define what public reaction might be.

“Some governors, alarmed at the deaths in prisons and jails and worried about the risk to surrounding communities, are listening—sort of, with an ear attuned to the political liability,” said Ms. Bradley Hagerty. “More than half of the states have agreed to release people convicted of low-level crimes, people who are nearing the end of their sentences, or people who merit compassionate release, such as pregnant people or older, vulnerable inmates.”

Ms. Porter expressed frustration that guidelines to fight the pandemic offered by epidemiologists and other medical experts have been ignored by U.S. prisons, exacerbating an already dire situation.

“Unless municipalities reduce the number of people in detention, people will die. It’s hard to imagine that once Covid-19 is inside, there won’t be a number of people getting it,” she said.

“We’re getting more information that people around the country are getting it. It’s distressing that they can’t protect themselves like those living in free communities. It’s very scary. I just hope that people get the help that they need and that we can help.”

Ms. Porter said more states are releasing incarcerated individuals but “certainly not a majority, and those who’re doing it is doing it in incredibly modest terms.”

Prison activists, civil and human rights advocates and families of the incarcerated, have filed lawsuits, protested at penitentiaries and detention centers, written letters, signed petitions and used various modes to pressure public officials. They’re demanding the release of those trapped in conditions conducive to the emergence and pervasive spread of coronavirus.

Tens of thousands are at risk, Ms. Taifa said.

“Prisons are so overcrowded because of the war on drugs. There are too many damn people in prisons,” she said. “Many of them were over-sentenced, elderly and most are vulnerable to contracting the disease. Prisons and jails are incubators, petri dish. Correctional workers go back to communities every day.

“Staff is working without proper PPEs, there is inadequate distancing and shortages of sanitary items. Black people are most affected. This is a serious situation. I am shocked there has not been more unrest and uprisings.”

Scott Roberts, Color of Change’s senior director of Criminal Justice Campaigns, said what’s occurring in the criminal justice system reflects an unjust and dangerously biased system that disproportionately punishes Black and Brown people.

“The vast majority who are in prison are not given a death sentence, but their lives are not as valued. It’s a political calculus that if people die in prison because of coronavirus, it’s cool,” he said.

“There is also a fear of backlash, as in Willie Horton. They’re afraid of being blamed if someone they release from jail commits a crime and they lose re-election. It’s up to all of us who care, to change the political calculus. We have to pressure them to let people out and not cause them to die unnecessarily.”

Ms. Porter, director of advocacy for the Sentencing Project, said the first and most obvious action is to release older incarcerated individuals, the elderly and non-violent offenders—all of whom are less likely to be a threat to the community.

“Some detention facilities are operating at 130 percent of capacity. Social distancing is impossible when people are living dorm-style, crowded in gyms and large spaces. People are crowded and packed into these prison warehouses,” she said.

Ms. Porter said the goal is to decarcerate jails by releasing the medically vulnerable.

“There are public safety benefits: those who are middle-aged have lower levels of recidivism. We could move people into the communities to be freer and healthier. People who are a year or less to exit prison should also be released. They should already have transition plans,” she explained.

Ms. Taifa agreed.

“The Justice Roundtable has submitted a comprehensive set of recommendations to Congress that will alleviate the Covid-19 pandemic relating to prisons and jails,” she said. “These provisions ensure safe conditions for those who remain incarcerated; the reduction of incarceration levels to end facility overcrowding and limit the spread of the virus; and supporting safe and effective reentry to the community.”

She said members of the Roundtable are calling on President Trump to exercise his unique authority to commute federal prison sentences for vulnerable populations.

“We have been in the courts calling for the compassionate release of at-risk populations due to the extraordinary and compelling circumstance of the pandemic,” said the attorney. “It is time that policies shift from over-punishment and mass incarceration to the promotion of compassion and justice.”

Donnna Muhammad contributed to this report