By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

Ten years after tragedy, a legacy is built, lives changed through struggle, sacrifice and service

Ten years after Oscar Grant, III was killed by a White officer on a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) District platform, his family copes by pouring out their blood, sweat and tears to aid others suffering similar losses. And, his name and legacy live through their commitment and service to young Black men like Oscar, young women and the cause of justice.

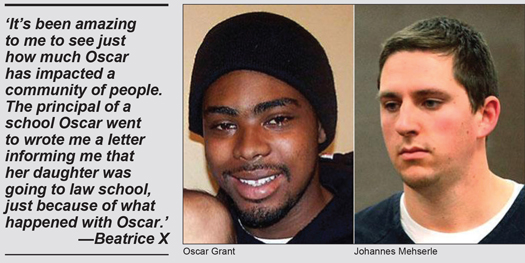

The 22-year-old was immortalized in award-winning Bay Area filmmaker Ryan Coogler’s film “Fruitvale,” named after the subway station platform on which he was fatally shot in the back by Johannes Mehserle. Oscar was subdued on the station platform New Year’s Day 2009, and his killer insisted the shooting was an accident. The BART security officer said he reached for his gun instead of a taser. With the trial moved from Oakland, a Los Angeles County jury convicted Mr. Mehserle of involuntary manslaughter in July 2010.

The tragedy, captured on cell phone and other video, stunned the nation.

But in early June, the young Black father’s family celebrated the unveiling of “Long Live Oscar Grant,” a mural painted by local artist Senay “Refa One” Alkebulan. “Oscar Grant III Way” was also unveiled that same day. The mural is located on a west exterior wall by the bus area of Fruitvale Station and cost $38,000. “Oscar Grant III Way,” an unnamed road in front of the station runs about one block long.

“It’s been 10 years since the death of Oscar Grant and BART worked closely with his family to create a lasting tribute and provide a place for reflection at the Fruitvale Station,” said BART Director Lateefah Simon in a press statement.

“It’s still hard,” admits Oscar’s mother.

“I’m really working to try to help other mothers so they don’t have to go through what I went through, trying to turn my pain into some type of purpose so that other mothers won’t have to face what I’m facing by having the loss of my son,” said Wanda Johnson.

Through the Oscar Grant, III Foundation, she works to help educate Oakland youth through tutoring, providing college scholarships in her son’s name, and offers recreation and athletics through the Oscar Grant Ballers youth basketball league. She also lobbies lawmakers and others as an advocate for police accountability.

Oscar loved basketball, said his mother, so the family felt starting a team in his name would be fitting. “We didn’t know what we were doing. We just gave it a shot, and have been doing it for five years now,” she said.

The first year was rough, but now there are 40 players on three different teams, added Ms. Johnson. “It’s really been fun to watch. They’ve graduated from the team. They’ve graduated from high school. They’re in college now, some of them, and it’s just amazing to watch,” she said.

One former player attends Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, and three others attend schools in the University of California system.

“It has given me a sense of peace from the pain that I’m facing these 10 years … . We need to hold officers accountable for their actions, and not just accountable, but we need to really rethink the way that we hire officers; rethink the way that they are trained,” Ms. Johnson told The Final Call. “It’s one of the easiest jobs to go to kill someone and still receive a paycheck, while you’re sitting at home whether it be for one week or one year.”

Tatiana, Oscar’s 15-year-old daughter, played on the OG Ballers girl’s basketball team last year, said her grandmother. “We try to keep her busy doing things to keep her time filled, because it has impacted her. She has felt particular ways, because her cousins and her friends have fathers at home, but she really doesn’t have her real dad at home, and so it affects her, hearing people talk about it,” said Ms. Johnson.

Her great uncle, Cephus “Uncle Bobby” Johnson, tries to help alleviate some of that pain and fill the void. “She’s really mature and I’m going to try to give as much guidance as I can as an uncle and do what I can for Oscar based on what he would have done for her,” said the activist who is widely known as Uncle Bobby.

Tatiana moved him tremendously when she spoke at the June 8 unveiling of the mural. She acknowledged her uncles, Oscar’s friends who were on the platform with him the night he was killed and they were roughed up and traumatized by police. Their pain is just so rough, Uncle Bobby said.

“They’ve never all had any real voice that they can really share because their pain just to them is still so raw. But Tatiana, this year, was able to bring them all up on the stage which is a big, big achievement in itself,” he continued.

When asked what they thought of the mural and street naming, one of Oscar’s friends replied, “I’d rather not be here.” He would rather have Oscar alive.

After successfully running the Oscar Grant Foundation, Uncle Bobby and his wife started the Love Not Blood Campaign and handed the foundation over to Oscar’s mom. He founded and nurtured the Oscar Grant Foundation with a determination that no one would co-opt his sister or her son’s legacy.

The family members have been active and outspoken in Oakland, across the state of California, and have traveled to other places, sometimes because of police shootings or to call for police accountability and to tell Oscar’s story. The Love Not Blood Campaign recently traveled to London to train others and advocate for victims of police violence. Uncle Bobby and his wife, Beatrice X, who is known as “Auntie B,” also co-founded California Families United 4 Justice, which has bolstered efforts to pass police accountability and police reform bills.

“The Grant family grew from being mere victims of a crime to advocates for justice, and part of the healing process for them has been to be participants in bringing justice in the murder of their son, brother and nephew,” said Student Minister Abdul Sabur Muhammad of Muhammad Mosque No. 26B in Oakland. He was an early supporter of the family and their demand for justice.

“I’m confident that little action would have occurred, but because of the organizing capacity of the Bay Area Nation of Islam and activists that worked along our side, there is today multiple forms of police accountability legislation,” stated Min. Muhammad, who authored the book “Grant Justice: Lessons Learned Fighting for Justice in the Murder of Oscar Grant.”

In Oscar’s case, he said, the community recognized swiftly that if he could be killed, anyone could die the same way, which led to the poignant cry, “I Am Oscar Grant!”

Two days after Mr. Mehserle was sentenced to two years in prison, Uncle Bobby was called and rushed to embrace the family of Derrick Jones. The 37-year-old was gunned down by two Oakland Police officers on November 8, 2010 following a domestic dispute.

According to police, during a foot chase, he supposedly reached for his waistband and produced a metal object, but he was unarmed. The district attorney’s office did not file criminal charges, and the officers were cleared in a federal wrongful death lawsuit filed by his widow.

“I remember him (Uncle Bobby) saying, at that time, ‘Wow! This is it! Hugging this father, and loving this family, has given me strength to fight this beast,’ ” recalled his wife.

After that, came outreach to the family of Trayvon Martin, a Black 17 year old killed by vigilante George Zimmerman, who was acquitted of charges in the fatal shooting. Then there was Michael Brown, Jr., 18, killed by former Ferguson, Mo., police officer Darren Wilson, who was never charged with anything. The list of families touched by police and other violence has grown. They have found an ally, supporter and comforter in Uncle Bobby and his wife.

“It’s been amazing to me to see just how much Oscar has impacted a community of people. The principal of a school Oscar went to wrote me a letter informing me that her daughter was going to law school, just because of what happened with Oscar,” said Beatrice X. “I’ve seen so many good things come out of something so horrific.”

She stressed that 10 years later, it’s important to remember heroes of the Justice for Oscar Grant Movement, like now-deceased Bishop Gordon Humphreys, Jr., who opened his church every Saturday for town hall meetings. Then there were diehards, like the youth who took to the streets in protest, and mature, seasoned organizers who mobilized action in the streets from behind the scenes through intense, consistent planning meetings in the Oakland Hills, she recalled.

“The unveiling was for me just beautiful! I was praising Allah (God) and rejoicing in the fact that there was a mural of Oscar Grant and there was an Oscar Grant III Way, because I’m telling you, BART was not having it,” said Beatrice X.

The idea for the street renaming came the day Oscar was fatally shot while handcuffed, face down on the train platform. Many asked for the renaming to happen a decade ago, she said. “BART was like, ‘Oh no!’ and BART really didn’t want to do the mural or the name change,” she told The Final Call. The city of Oakland went back and forth with BART for over two years concerning that property, she added.

“I definitely feel good about it. It’s been a long, hard road to bring about the mural, as well as the street naming where it became a reality, but really it all came from the community again, standing with us, supporting us, embracing us,” said Uncle Bobby.

Mr. Mehserle, since freed, has gone into hiding and changed his name, he added. “Nobody knows who he is yet. We haven’t been able to figure that out, but he definitely has changed his name … even his work location,” Uncle Bobby added.