By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

Last Thanksgiving was a particularly bad holiday for the families of six Black females who died at a time often used to focus on reasons to be grateful. But advocates say domestic violence and assaults against Black women still draw too little attention, outrage and protest.

The five women and one teenager who died in a deadly week last November lost their lives at the hands of their husbands, ex-husbands, or boyfriends in different parts of the country.

“We are in a crisis and the crisis we often talk about is the external–people outside of our community who seek to do us harm–and that is a real danger. But the silent killing of Black women is at the hands of those within our community,” said Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis, a licensed psychologist and ordained minister. She has worked nationally and internationally to provide relief and empowerment to marginalized people, including women. She is an associate professor at Pepperdine University and a past president of the Society for the Psychology of Women.

For Black women, like other women, threats come most often from people who know, claim to love or claim to have loved them.

Dr. Bryant Davis feels silence about domestic abuse toward Black females is multiplied as the media decides which victims deserve to be written or talked about. “Often those are not Black women, but even within our communities when the offender, the perpetrator, the murderer is someone from within our community, then we also are silent about it and so the silence is killing us both outside and inside,” she said.

On November 17, 2018, firefighters found sisters Uniek Atkins, 27, and Sierra Brown, 16, dead with gunshot wounds after extinguishing flames in their Westchester apartment, about 20 miles southwest of Los Angeles. Two days later, police arrested a 17 year old, a boyfriend of one of the victims, on suspicion of murder and another minor as an accessory.

Across the country in Shaker Heights, Ohio, 45-year-old Aisha Fraser Mason’s ex-husband allegedly stabbed her to death in front of their two children, 8 and 11, and her sister. She was a beloved elementary school teacher for 16 years. Her killer, Lance Mason, was a former Cuyahoga County, Ohio judge. He tried to flee when her sister called 911 and was arrested after crashing into a police cruiser. He has pleaded not guilty to her murder.

In an August 2014 attack with their daughters watching, authorities said Mr. Mason punched his wife 20 times while they were driving and repeatedly slammed her face into the dashboard. She tried to escape at a red light but he caught her, punched her again and bit her face. He pled guilty to attempted felonious assault and domestic violence, was sentenced to a two year sentence, and released after nine months.

Critics say his professional status and connections contributed to leniency in his case, including character reference letters from prominent legal and political figures. It was another part of how the system failed Ms. Fraser Mason.

“One of our challenges around safety is we have this myth or idea of what an abuser looks like, and so again and again we assume that by looking at a person we can tell if they would be violent or if they would be abusive, and usually that caricature is someone who is low income, someone who’s on drugs,” explained Dr. Bryant-Davis.

“This is the person you need to look out for, or so we are told directly or indirectly, but when you are dealing with someone who has an education, someone who has a nice job, someone who came from a ‘nice’ family, someone who talks well or who is charismatic, then people are less likely to believe that this person is being abusive,” she continued.

Lance Mason and Aisha Fraser Mason were educated, accomplished and professional. He was a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. She was a member of Delta Sigma Theta. “Our prayers and deepest condolences are with the family and loved ones of soror Aisha Fraser Mason who recently lost her life due to a senseless act of violence,” her sorority tweeted after her death.

In February, a bill was introduced in the Ohio state legislature, named for Aisha Fraser, and tries to better protect domestic violence victims. “Aisha’s Law has three parts: After a domestic violence incident, a victim would be provided a questionnaire through which police and domestic violence advocates could assess her level of danger for future intimate partner violence; the victim and perpetrator would be referred to a community committee made up of police and advocates who could connect them to resources, such as rehab or housing; and offenders would be prohibited from pleading down violent felonies to lesser charges when they have prior serious or violent felony convictions,” Cleveland.com reported.Two key ways the criminal justice system fails Blacks suffering from partner abuse are distrust of police due to brutality and killings, which makes some women hesitant to call for help, and perpetrators get less time for harming Black women than for harming White women, said Dr. Bryant-Davis.

“Some people have in their mind, ‘I want them to stop hurting me, but I’m not trying to get them killed,’ so you have some people say just as a rule that they’ll never call the police on a Black man period, but their lives are literally in jeopardy, and their children,” Dr. Bryant-Davis told The Final Call.

“Whether partner abuse, sexual assault, or childhood sexual abuse, the length of punishments given or even the likelihood of a conviction, of being believed, of being supported shows Black women are not deemed as valuable or as worthy of protection,” she added.

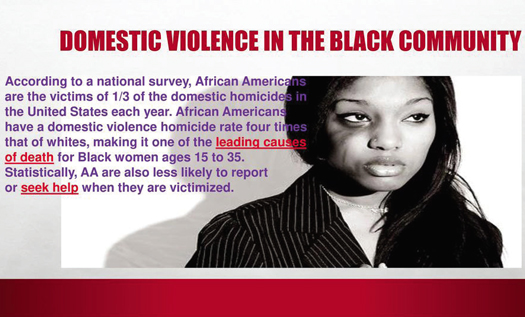

According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Black women face a particularly high risk of being killed at the hands of a man. A 2015 Violence Policy Center study found that Black women were two-and-a-half times more likely to be murdered by men than their White counterparts. More than nine in ten Black female victims knew their killers.

In Stefanie Vallery’s case, she and her husband Michael Vallery of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, were ending their 14-year marriage. During an argument at her home, he left, then returned and stabbed her, despite family members’ attempts to stop the attack. She died in her 25-year-old daughter Danielle Scott’s arms. “Then he kicked down the door and came back again. I turned to him and said: ‘You killed my momma.’ He just didn’t care–he ran up and stabbed (her) some more and ran out,” Ms. Scott told The Advocate newspaper.

In Chicago, Dr. Tamara O’Neal’s ex-fiancé Juan Lopez shot her execution style during an argument Nov. 19 in the parking lot of Mercy Hospital where she worked as an emergency room physician. Police say he shot at them before fleeing into the hospital where a shoot-out occurred. Mr. Lopez fatally shot another hospital employee, pharmacy resident Dayna Less, and Chicago police officer Samuel Jimenez before shooting himself, according to police. According to investigators, Dr. O’Neal had ended recently her engagement to Mr. Lopez.

He died after shooting himself in the head though wounded in a shootout with police, said authorities.

On Thanksgiving morning in Lewisville, Texas, police say 30-year-old Kishana Jeffers’ estranged husband Darryl Stegall kicked her door in and shot her in the head in front of their three children, 7, 9 and 10, at her apartment. Moments later he shot himself in the head. He died later from the self-inflicted wound, said police.

Women go through great lengths to protect themselves–working through the system, getting restraining orders, getting protective orders, going to shelters, and calling police but in a lot of ways the system has failed, said Sulaiman Nuriddin, a longtime advocate for justice and safety for women and girls. He worked for more than three decades for the Atlanta, Ga.-based advocacy group Men Stopping Violence.

“I believe the system may be doing the best it can. At the same time, it’s not serving the needs of the women and girls and children and men in our community,” he said. In addition to the criminal legal system, he suggests looking toward empowering communities to deal with domestic violence. He desires to see a support network in communities that make a difference, a place like a house of worship, where victims can get help and perpetrators can be held accountable. “They begin to set up what guidelines, what ideas, what is necessary to create safe communities, so we begin to take responsibility for what’s happening in our community. Because what we fail to understand is a crime to anyone is also a crime to that whole community that I live in,” Mr. Nuriddin argued.

It’s also important that families really focus attention on their boys, Dr. Bryant-Davis noted. The focus is often on how girls can prevent or look out for domestic violence, but parents with sons must be very intentional and give clear instructions about dating beyond how not to get a girl pregnant, she added.

Boys need to be taught how to treat people, what consent looks like, and what earned respect looks like as opposed to making someone afraid of them, she said.

Violence, jealousy, and control are not love, Dr. Bryant-Davis said.

Emotional abuse includes controlling behavior, name calling, putting someone down, demeaning them and their dreams, constant monitoring, envy, and baseless accusations, she said.

Dr. Bryant-Davis urged family and friends of those suffering from domestic violence to have an element of patience. It’s hard to escape an abusive relationship, she said. “One, you’re at increased risk of homicide when you try to leave, so more women are killed when they’re in that planning stage of trying to get out so it can be very scary,” Dr. Bryant-Davis explained. “The other piece is as a culture, we teach people to fight for love, to fight for their relationships, to fight for their marriages, meaning to hold on even when they’re treated badly. So sometimes family and friends can get frustrated and tired of dealing with a loved one who is in that circumstance. But, if we give up on them, they really have no one and then they’re isolated with the partner.”