By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

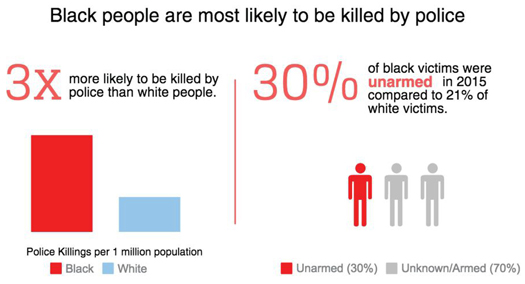

Police violence is far from over, with Blacks being one-quarter of those killed by police and Black victims also are often unarmed, according to a new report.

Mapping Police Violence reported that police killed 1,129 people last year.

Among them, 147 were unarmed: Blacks (48), Hispanic (34), Native American (2), Asian/Pacific Islander, White (50), and 11 unknown.

The numbers suggest people can, without a doubt, expect little change in 2018 unless there is more law enforcement accountability, insist police reform advocates.

“When you have an organization that’s run without consequences, or any type of punishment, they will continue to do the same thing,” said Harry “Spike” Moss, a longtime activist in Minnesota.

He added, the worst thing about the police is that rank-and-file membership is comprised of the average Caucasian who harbors racist views that permeate the country.

“When you open the door to such broad racism and hate that’s taught to Caucasian people at such a young age, you’re talking about hateful people who have been empowered to law and a badge, and then given a weapon, it’s almost virtually an impossibility for several years of change,” Mr. Moss told The Final Call.

Who, where you live and your race played major roles in whether you were likely to die at the hands of law enforcement officers, according to national trends outlined in Mapping Violence.

Blacks were more likely to be killed by police, more likely to be unarmed and less likely to be threatening someone when killed, indicated data surveyed by Samuel Sinyangwe, a data scientist and policy analyst, Deray McKesson, organizer and activist, and Brittany Packnett, activist and educator.

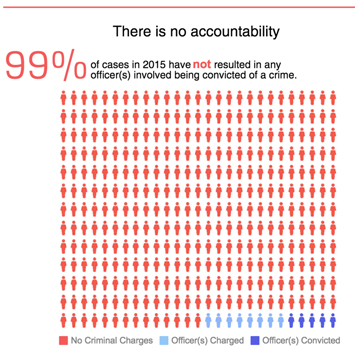

They found that of the 1,129 people killed by police in 2017, 1,039 (92 percent) were shot. Officers were charged with a crime in only 12 (1 percent) of the cases, and nine of those cases had video evidence.

The data comes from media reports, obituaries, public records, databases, and national media outlets.

“Our analysis suggests the majority of killings by police in 2017 could have been prevented and that specific policies and practices might prevent police killings in the future,” stated the Mapping Violence team.

Prevent deaths by limiting police interventions and use of force, improve community interactions with police, demilitarize police forces, and end for-profit policing, they recommended.

Mr. Moss said other things working against Blacks are laws allowing police to kill if they feel threatened.

Just before the New Year on Dec. 29, Angela Williams claimed Troy, Ala., police beat her son Ulysses Wilkerson, who ran after they startled him. Ms. Williams posted photos of her son’s swollen, bloody facial injuries on social media.

According to media reports, Ms. Williams’ attorneys allege the 17-year-old was walking behind a downtown business before police severely injured him. Her attorneys have demanded body camera videos or dash cam footage be released.

Attorney Angel Harris, assistant counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, said the Tennessee v. Garner case underscores why changing legal standards is so critical. She spoke to families of loved ones killed by police at the Families United 4 Justice national conference in Detroit, Mich., last summer.

On Oct. 3, 1974, Memphis police suspected eighth grader Edward Garner of a home robbery. While jumping over a fence as he fled, Officer Elton Hymon shot him in the back of the head.

The teen’s father sued the Supreme Court, arguing the police violated his son’s constitutional rights.

The Supreme Court ruled in March, 1985 that “such force may not be used unless it is necessary to prevent the escape and the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.”

“The ruling that came out of that case is, unfortunately, why so many officers get away with murdering your family members,” Atty. Harris said. “Without changing that burden, police officers will be able to continue to come into court and say I thought he was going to injure me. I thought that he had a weapon, and we all know that that’s not true. We all know that if an eighth grader is jumping over a fence, there is no way that he is presenting a danger to that officer and that his (officer’s) actions aren’t justifiable in any way.”

Repeat police offenders are also a part of the problem, Mapping Police Violence reported.

It found that at least 43 officers had shot or killed someone before, and, 12 had multiple shootings.

In addition, police recruits spend seven times as many hours training to shoot (58 hours) than they do training to de-escalate situations (eight hours), the report said.

Most killings (631) began with police responding to suspected non-violent offenses or cases where no crime was reported. Eighty-seven people were killed after police stopped them for a traffic violation.

The dominant narrative around race and law enforcement is that crime rates drive police behavior, according to the Center for Policing Equity, a New York-based research think tank. However, even with a conservative estimate of bias, its 2016 analysis of a dozen law enforcement departments from geographically and demographically diverse locations revealed that racial disparities in police use of force persist even when controlling for arrest demographics. Their analysis was called “The Science of Justice: Race, Arrests and Police Use of Force.”

The bottom line is Blacks face a system of disrespect, said Mr. Moss. “We have lived in this country without freedom, justice, equality all these generations. It’s impossible. You go to a 12-person jury in a country that says you will be judged by your peers, then you walk in the room, and it’s all White people. … When they judge you, they’re judging something they hate. When you’re sitting there, ‘you’ve got to be wrong, because I hate you,’” he said.

“We are so beholden to our oppressor, we don’t want to do what we need to do, which is protect ourselves by becoming a nation inside the nation, and declare some sovereign ground that we can live on, because they won’t allow us to live with them,” said Mr. Moss, echoing the continuous guidance and instructions of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan and his teacher the Honorable Elijah Muhammad.

“When Ronald Reagan became president, he brought the war games he and his staff were playing in California under his governorship into the White House even moreso, because they expected [urban revolts] since 1967 and 1968, when the riots broke out and Dr. King was assassinated,” said Min. Farrakhan in Nov. 16 press conference address and warning to President Donald Trump, and the government and people of the U.S. at the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C.

Min. Farrakhan said, “The government of America knew that the Black youth were dangerous. Black folk were becoming more militant, and instead of seeing that there has to be a solution, let’s separate the two people. But Reagan didn’t want that: [Instead] ‘Kill them!’ ”

Something must be done, but people absolutely are not following Min. Farrakhan’s guidance, stated Damon K. Jones, New York representative of Blacks in Law Enforcement of America.

Until they reach that “Aha!” moment and submit, Mr. Jones said Blacks have to use their voting power, attend local city hall and legislative meetings, and make their voices heard on problems of police violence.

“Start to really examine our Black elected officials. Give them a grade, and start really looking at them, instead of just running to the polls every election time, actually sit and ask them, what have you done for us lately? How many young, Black teenagers have you saved from being killed by police? What did you change? We’ve got to start asking these questions,” Mr. Jones told The Final Call.

“In some instances, we’re already separated! We’re already separated in these towns, but in the same towns that we have, we don’t have any power and then the Black people we put in office … we can’t afford to go to $250 luncheons and stuff like that, so we’re not the ones calling the shots for the Black people that look like us that we put in office anyway,” Mr. Jones said.