ASKIAM and Brian Muhammad, The Final Call

The year 1967 was known as the “long hot summer,” in the United States. It was a span marked by uprisings, riots and rebellions as 159 cities across the country exploded in violence. Milwaukee, Buffalo, N.Y., Tampa, Fla., Boston, Atlanta, Minneapolis, Minn. and Cincinnati were just a few of the cities where Black oppression, discontent and dissatisfaction reached the boiling point. Two cities in particular, Detroit and Newark, set a critical tone during the summer of uprising and rebellion.

That year, public attention in the country was riveted on “The D,” where, it seemed, all the demands of Black people for justice from law enforcement and the courts; equality in education, employment, housing; and freedom erupted in one week; even more violently than they had in Harlem in 1964; in Watts in 1965; in Chicago in 1966.

For nearly a dozen weeks during the “long hot summer” of 1967, Aretha Franklin’s Billboard magazine Number one hit “Respect,” set the tone of the day. World Heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali refused induction into the Army in late April; Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) and Willie Ricks (Mukasa) declared “Black Power,” during a “march against fear” in Mississippi in June.

Men combed the streets of the major cities selling the Muhammad Speaks newspaper. Black people were teeming all over the United States, Africa and the Caribbean.

Opposition to the Vietnam War was swelling all over the country. There was an equally unpopular military draft in effect, which disproportionately chose Black youth, and the poor, to die in that bloody and immoral war, while wealthy elites like Mitt Romney and Donald J. Trump avoided service, receiving multiple deferments.

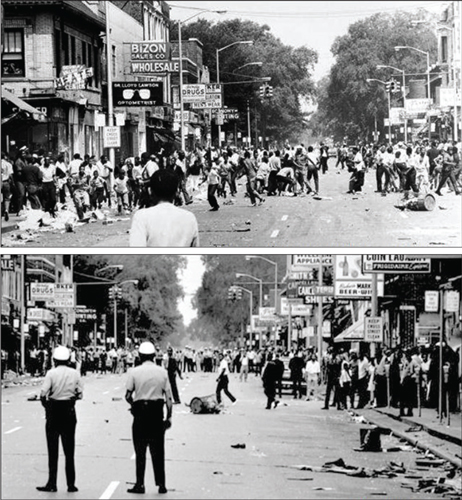

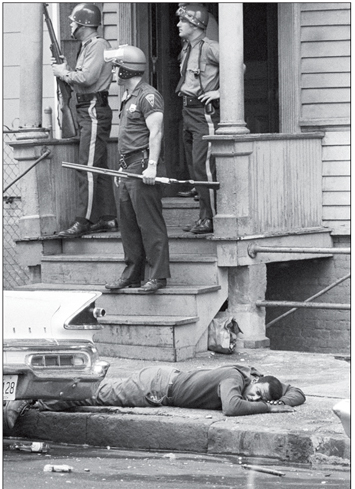

On July 12, 1967 in Newark, N.J. Black folks responded to yet another police brutality incident there, with a four-day rebellion which left 26 dead and hundreds injured.

Then, on July 23, 1967 Detroit police raided an after hours club at 12th Street and Clairmount Avenue, where they found dozens of people at a party for two returning Vietnam veterans. The resulting arrests and melee lit the fuse.

Detroit exploded: 2,000 were injured; 43 died; 3,800 were arrested. Troops from the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division and the 101st Airborne Division were required to restore order.

“The uprising in 1967 was a natural reaction to an oppressed people who was tired of being brutalized by the occupying force in their community–the police; lack of educational resources, lack of quality, affordable housing, health care and so many of the other issues we find ourselves in today,” said Dr. Wilmer Leon, a political scientist and radio show host.

Lamont Causey and his his family have lived in the Detroit area for nearly 70 years. He was seven years old when the riots occurred. He remembers when two of his uncles were arrested in his backyard for going to the afterhours joints. He remembers when the street lights were knocked out during the day time causing it to be black at night.

Kirk Sanders was 6 years old and he also remembers that time clearly. “The National Guard was patrolling the streets and alleyways looking for looters and checking houses for stolen property. When they came to our house, I just knew we were going to jail or be shot or something. I was scared because I looted and ended up with toys and two pair of shoes that were both left foot. So I started crying cause I wanted to go back and get the right shoes, but couldn’t.” He laughs now, but at the time it was a terrifying experience. Mr. Causey and Mr. Sanders helped organize a 50th anniversary commemoration of the Detroit riots in the city.

Back then, beleaguered on all sides, President Lyndon Johnson ordered a National Commission on Civil Disorders, literally before law and order had been restored in Detroit. It was headed by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, and was known as the “Kerner Commission.” The President challenged the commission to answer three questions in their findings: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?”

The resulting report codified the language: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, and one White–separate and unequal.” And so the society remains, to this date.

The report said one main cause of urban violence was White racism and it suggested that White America bore much of the responsibility for Black rioting and rebellion. Mr. Johnson rejected the commission’s report. He felt his achievements in winning Civil Rights legislation were sufficient. The Kerner Commission’s recommendations, included: creating new jobs; constructing new housing; diversifying and sensitizing police forces.

In the 1960s both Dr. Martin Luther King and Minister Malcolm X gave dire and somber outlooks to where America was headed. During a radio interview in 1961, Min. Malcolm X said it would take this country another 100 years from that day, to achieve school integration at the rate they were proceeding since the 1954 Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision ordering school integration.

Similarly, in 1964 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made an equally dire forecast about the rate of progress registering Blacks to vote in the state of Mississippi. “About 192 Negroes were registered on the average a month in the state of Mississippi, all over the state, 192 a month,” Dr. King said at a rally for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1964. “The rebellions really represented the growing fury that existed within Black America about the urban condition,” Bill Fletcher, a labor and human rights activist, told The Final Call in a telephone interview.

He pointed out that the turmoil by and large came after landmark victories of the Civil Rights Acts and the Voting Rights Acts.

“There was this illusion that was being perpetrated–largely by liberals–that the problem of the U.S. was the south and that there were no problems in the north, Midwest and west coast,” Mr. Fletcher explained.

By the 1950s through the 1960s a combination of circumstances adversely affected urban America. The mixture of “de-facto segregation, suburbanization, and the relocation of industry” became a perfect storm that ill affected the Black and poor.

“You had the exit of large numbers of White people from major cities going into suburban areas,” Mr. Fletcher said.

While there has been little progress toward addressing the core issues Black folks faced in Detroit, Newark and other cities around the nation 50 years ago, the political climate today is not as explosive. Success by Black politicians, on local, statewide, and national levels; a proliferation of high profile Black personalities in sports, athletes, coaches, managers; breakthroughs in science and entertainment, business and finance; has tempered contemporary Black responses, except when it comes to the murder of innocent Black people by trigger-happy White cops who are frequently exonerated.

Taking stock of the situation of Black people in 2017, despite many spectacular victories, on the whole Black people are not much better off for having sought to integrate into American society, than they were 50-plus years ago.

And yet, in the 56 years since the Malcolm X interview; in the 53 years after Dr. King’s remarks during the SNCC “Freedom Summer” of 1964; and in the 50 years since the Detroit and Newark uprisings, voter suppression–labeled combating “voter fraud”–is the order of the day and achieving the goal of school integration remains elusive.

Today, public schools–62 years after the Supreme Court’s historic Brown v. Board of Education decision–are increasingly segregated by race and class, according to new findings by Congress’ watchdog agency that echo what advocates for low-income and minority students have said for years.

“Investigators with the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that from the 2000-2001 to the 2013-2014 school year, both the percentage of K-12 public schools in high-poverty and the percentage comprised of mostly African-American or Hispanic students grew significantly, more than doubling, from 7,009 schools to 15,089 schools,” according to a report in USA Today. “The percentage of all schools with so-called racial or socioeconomic isolation grew from 9 percent to 16 percent.”

Mr. Fletcher, looking at the current state of cities that experienced civil unrest in hindsight says having Black leadership alone back then was not sufficient. “They did not by and large introduce alternative economic development strategy,” said Mr. Fletcher, speaking in particular about the Black political leadership class.

“They ended up being squeezed and in some cases strangled by White Republicans in the state legislatures, who are based in the suburbs and rural areas.”

Being Black and rising to political office proved not enough. The Black political leaders fell into the mold of going along with the status quo of American capitalism, he stated.

Failure to think outside the box for economic development has brought about loss and further lack of control, added Mr. Fletcher. Current gentrification in places like Harlem, N.Y., as the historic “capital of Black America” is becoming an increasingly White community campaigning to change its name.

“Some realtors and store owners are rebranding the area from 110th to 125th Streets as SoHa, short for South Harlem,” said a NY1.com article about the neighborhood. Residents told NY1 that it’s an insult to change the name of Harlem and it’s a sign of “gentrification run amok.”

Another example is Washington, D.C., morphing from being the “Chocolate City” to “Latte City” which was driven by years of deliberate neglect and blight by developers and bankers strategizing a retaking of urban centers.

“It’s hard to say that for some in this country, that things have not improved, but for the masses of African-Americans, we are still battling the very same issues that we were battling in ’67,” said Dr. Leon.

He said moving forward today will require that Black people mature politically. “We have to come to the realization that the politics of personality and the politics of pigment or phenotype can never replace the politics of substantive public policy,” he reasoned.

Black folks, cannot simply wait on integration. Instead, for the last 50 years since “Black Power,” and “Respect,” and boycotting the U.S. military, such as was going on at the time of the uprisings in Newark and Detroit in late July, 1967, Black folks today have been marching along the right “road to freedom,” only headed in the wrong direction.

Blacks must stand for themselves and demand more from those they put in positions of power, said Dr. Leon. He said the community must also support voices of empowerment like the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan and others who are challenging the forces of oppression.

Dr. Leon suggested that Blacks must battle against being “afraid of being alienated by their White benefactors” whose policies perpetuate the negative conditions.

“You don’t find that fear among White people,” Dr. Leon said.

(Mahalieka Muhammad contributed to this article from Detroit)