By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

LOS ANGELES–Activists, non-profits, grassroots organizations, gang members, gang intervention workers, and artists marked the 25th Anniversary of the Los Angeles Uprising and the Los Angeles Gang Peace Treaty with panel discussions, a march, rally, film screenings, food, music and more.

Have things changed in community-police relations and police brutality since L.A. went up in smoke 25 years ago, in part after a predominantly White jury acquitted four White officers of the savage beating of Black motorist Rodney King?

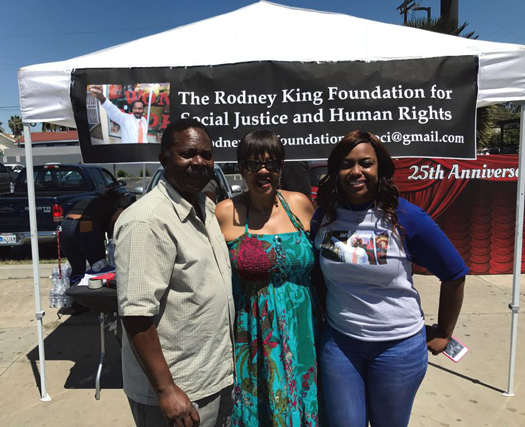

Lora Dene King was seven-years-old when police pummeled her father after a high speed chase. She has mixed emotions about her father’s legacy, which she feels will always live on.

As for change, she’s seen very little. “It’s been adjusted and shifted, but I don’t think there’s been any change, and the magnitude of people dying is a serious matter, but I think the media has a tendency to replay it to condition us to think this is normal, and it’s not normal for people to get shot in broad daylight, at night, kids,” Ms. King said. “It’s crazy! It’s insane! You can’t condition a real human being to think that this is okay.”

What police did to her father affected him not only mentally, but in every way possible, she said. Many don’t realize he suffered a tremendous amount of brain damage, said Ms. King.

“I mean it still affects me day-to-day. It’s a struggle. You know, it’s a struggle,” she said. The circumstance surrounding her father’s death is still a head scratcher for her. She feels things don’t quite match up.

His death was ruled an accidental drowning on June 17, 2012, however, he was a proficient swimmer, she said. “So whatever happened, it happened before he hit the water,” Ms. King said.

“The sad part is that the county that he died in is bankrupt, so they just ruled it out. … I thought they didn’t do an extensive investigation,” she said.

The family of Latasha Harlins attended the march and rally in her honor.

Korean grocer Soon Ja Du, who was 51-years-old, shot the 15-year-old Black girl in the back of the head, claiming she was trying to steal a bottle of orange juice from a liquor market.

Ms. Du faced 1st degree murder charges for the March 16, 1992 shooting. She was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and received probation from a White, female judge. Outrage over her death, tensions with Korean store owners and the light sentence helped sparked the rebellion.

“Pretty much what we think about it now is what we thought about it then. Things, believe it or not have gotten progressively worse,” Student Minister Tony Muhammad of the Nation of Islam mosque in Los Angeles told The Final Call.

“As far as at the criminal justice system, the economic depression, the over-incarceration and criminalizing of young brothers who lived in that neighborhood, nothing as far as the state, city or county to this day is doing anything to kind of mitigate all of those circumstances,” he added.

Tybie O’bard recalled her best friend planned to become a lawyer, because she saw some injustices in their neighborhood.

“As a child, she knew that. And as kids in that neighborhood, you either grow up fast or you get swallowed whole,” Ms. O’bard said.

She still lives in the neighborhood. “Everything has changed now, but as far as the attitudes towards Blacks with Korean owners, it’s not as obvious as it once was, but it’s still there,” she continued.

Latasha Harlins’ friends and family joined Watts activists and peacekeepers for the 25th Anniversary of the Watts-L.A. Peace celebration. It’s theme was “Nobody Can Stop This War But Us.”

Activities included film screenings, “Imperial Dreams,” the story of reformed gangster Bobby “Yay Yay” Jones, and “Jim Brown’s Amer-I-Can Dream,” which chronicles the former NFL great’s work with ex-gang members to end gang violence, a panel discussion at the Lighthouse Church, and a special reception at LocoL Watts, which serves wholesome, quality food at affordable prices.

Gang peace came the day before South L.A. revolted against an unjust system, said architects of the peace treaty. However, little has been mentioned about their act of self-determination 25 years later, they said.

“It was a moment in which we redefined public safety. The Peace Treaty was a community strategy to address the heavy handed approach of law enforcement killing our children with impunity,” said Aqeela Sherrills, a co-founder of Amer-I-can.

The times are similar, he said.

“The community has never been protected or supported by law enforcement. I hear all across the country now where, ‘Oh! We have to create a better relationship with the police.’ I’m like, we didn’t have one! We never had one. It was that slave master-enslaved relationship,” Mr. Sherrills stated. “Even now they talk about the Rodney King trial as if Rodney King was on trial.”

He emphasized how Peace Treaty movement began in 1998. And in 1989, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam brought his “Stop the Killing Tour” to Los Angeles. “That really galvanized Crips and Bloods from all around the city to come together and talk about how can we stop this killing ourselves,” said Mr. Sherrills.

From there, consistent organizing started at Mr. Brown’s home. That activity birthed the Amer-I-Can Life Skills Management Program now being taught in schools, jails, and prisons across the country.

“We felt like our cries for help were falling consistently on deaf ears, because of this label gangs that was put on us. It dehumanized the people behind it, desensitized the public to our plight, so therefore, regardless of what we said, the system–even though they saw this video, and we had been complaining about this for years–still it was like ‘oh, that’s not happening to folks,’” Mr. Sherrils added.

His brother Daude Sherrills said the language of the Peace Treaty is about a way of life and crime and violence reduction. The gangs in Watts agreed to cease fire, then come together in a truce, and then declared they were working for peace, he explained.

“For over 25 years, we have done that, cease fires, developed truces, and created plans,” Daude Sherrils said.

“Seeing so much violence, death and the cycle of death and violence and destruction, for me, it had to be a change after,” he said, especially after he had a child.

At 50 he wants to continue to lay a foundation for liberation, helping people affected by poor education, poor housing, a lack of jobs and opportunities.

Other speakers were Rudolph “Rockhead” Johnson, former Compton Crip leader, now, coach of the I-Can Allstars Basketball program; Ms. Ferlin, Attorney Salamon Zavala, and panel facilitator Dr. Melina Abdullah, Black Lives Matter L.A. organizer and chair of the Pan African Studies Department at California State University L.A.

“V-Dog,” also known as Brother Wali, commended the event’s organizers. He said he was 13 and lived in the Jordan Downs Housing Projects, when the Peace Treaty was forged.

“These brothers motivated me to do what I do now. I’m the national field marshal of the Black Panther Party. It changed our lives forever, because we were watching them. We went to Jim’s house and Jim offered everything he could, and didn’t ask for nothing, but showed everybody love,” he said. “I never thought 20 years later or nothing like that that we’d be at this point,” said the 38-year-old.