By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

Statistics indicate U.S. HIV infection rates have declined, but Black women are still disproportionately affected by the disease compared to their female counterparts.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, rates of HIV infection among Black women fell 42 percent from 2005 to 2014.

In 2015, 4,524 Black women were diagnosed with HIV, compared to 1,131 Hispanic/Latino women and 1,431 White women, the CDC indicated.

“I’m concerned. I know that the last report coming out of CDC, they indicated that numbers are going down, but what we’re seeing is that Black women in the United States–based on our work and efforts–continue to be negatively impacted by the HIV-AIDS epidemic and that many of the socio-economic factors, as well as what we call environmental exposures, are not adequately being addressed by institutions as well as service providers,” said C. Virginia Fields, president and CEO of the New-York-based National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS, Inc.

She and other experts told The Final Call socio-economic factors related to increased risks for Black women include higher risk of intimate partner violence and related suppression, fears about condom use, no treatment for substance abuse and mental health conditions, and untreated sexually transmitted diseases.

“Our work continues in terms of advocating for programs and policies to reduce the health inequities that are experienced by Black women in America, despite what CDC reports might say. But this is based on being on the ground, what we’re experiencing in socio-economic factors, environmental exposures, and with that in mind we have to keep working,” Ms. Fields said.

Women have been a second thought in the entire AIDS epidemic and an afterthought in the cultures they live in, said Waheedah Shabazz-El, regional organizing director for Positive Women’s Network-USA.

“Black women, I think, we’re only about 12 percent of the population but we account for 65 percent of the new cases of HIV in the United States,” she said.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Black women make up 6.3 percent (20,597,514) of America’s total population (323,127,513).

Infection rates may be dropping, but one infection is too many in the narrative of an epidemic that’s been around for 35-years, she argued. “HIV is not new. It hasn’t just gotten here. People of color are not just impacted because of the color of their skin. People of color are impacted because there are other vulnerabilities to becoming HIV positive–people who are homeless, people who are poor, people who don’t have health insurance, people who can’t read,” Ms. Shabazz-El said.She’s seen a lot of literature saying HIV is preventable, but what’s left out is that it’s in an ideal world. And that type of messaging renders women feeling bad and like they’re totally at fault, the advocate noted.

An ideal world is free of homelessness, hunger, and mass incarceration, which all undergird the problem, Ms. Shabazz-El said. In the ideal world, communities are stabilized, everybody has health insurance, and age-appropriate reading resources, regardless of technology, she continued.

“HIV should be a human rights priority for all of us, and we should look at it that way because that’s what it is,” she said. Ms. Shabazz-El also stressed that there’s a difference between HIV risks, such as unprotected sex or sharing something that has to do with blood, and HIV vulnerability, such as where people live.

“Some of us live, date, shop, die, marry in the same zip code. We’re likely to pull from a contaminated pool if we’re always in the same zip code,” Ms. Shabazz-El stated.

Also missing from the messaging around HIV is that for a long time, people thought it was a gay disease that had nothing to do with women, and it wasn’t their business, she said.

“Now we’re finding out that it’s sitting right here in the middle of the heterosexual community … . It’s not that Black woman is doing something that other races aren’t doing, but the Black woman has more vulnerabilities to contracting this virus that is the positive proof of the socio-economic disparities,” she argued.

HIV/AIDS is still on fire among Black females 13 to 24 years old and older women, according to attorney Vanessa Johnson of the Positive Women’s Network-USA, the National Black Women’s HIV/AIDS Network, and the National Women and AIDS Collective.

“The young people, because they haven’t lived long enough, and in addition to that, if they’ve had traumatic family or life experiences, trust is an issue,” she said. “Older women are still believing that ‘I’m not one of those people that HIV would impact.’ They still think it’s gay men or sex workers or trans-women, everybody but a churchgoing women,” Atty. Johnson explained.

Also impacted are women in their 30s and 40s, who are transitioning in their relationships, as well as divorce and marriage rates, which Atty. Johnson labeled “weird.”

“It could be married, unmarried, or a lot of women think if ‘I’m with this man, then I’m okay,’ but then they might have had four relationships in a year,” she said.

“And then there’s still the issue of married women who believe that because they’re married, they’re protected, or women in long-term relationships that believe because they’ve been with this man forever, that that’s not going to happen to us … . But at the end of the day … unless you’re walking around with his genitalia in your pocketbook, how do you know?” Atty. Johnson asked.

She continued, “I think the canary in the mine is sexually transmitted diseases, and those are off the chain, particularly among young people.” She citied chlamydia as particularly dangerous because it could lead to sterility, but people overlook it because it’s not associated with death, she said.

“With HIV, we have treatment, but it’s treatment for life. … HIV is a robber. It robs families, communities, and future generations, because the connections are not being made,” she said.

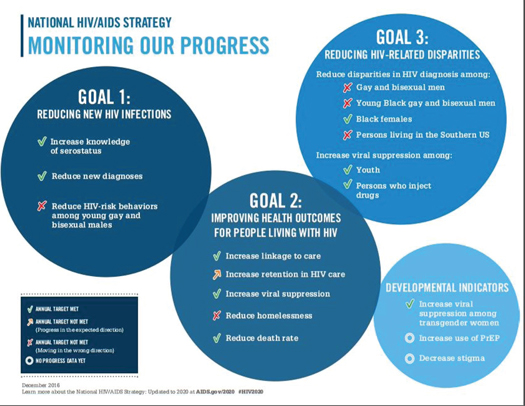

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy 2016 Progress Report updated to 2020 assessed accomplishments since the strategy’s first release in 2010 under President Barack Obama.

Its goals are to reduce new HIV infections, increase access to care and improve health outcomes among people living with HIV, reduce HIV-related health disparities and health inequities, and achieve a more coordinated national response.

New HIV diagnoses decreased seven percent from 2010 through 2013, according to the update. Eighty-seven percent of persons living with HIV are aware of their status, and 3 in 4 persons diagnosed are linked to care in one month, it reported.

However, though diagnoses dropped overall, progress in reducing the diagnosis disparity experienced in the Southern United States stalled, the report continued.

“Testing is important! Knowing your status is important! Staying STD free is important! Over 80 percent of women living with HIV were exposed by their primary monogamous sexual partner–spaces where they are supposed to feel safe and loved,” said Traci Bivens-Davis, chair of the Los Angeles Women’s Collaborative on HIV.

Some women develop the routine of testing while single, but, once in a seemingly monogamous relationship, they interrupt the pattern, she said.

“If somehow you don’t believe you are at risk, then you might be,” she cautioned.

Taking into context the mental, physical, and psychological realities of girls before they become women is crucial to achieving a cure, she said.

“Today, as Black girls are increasingly pushed out of schools and into prisons, we must consider what messages and opportunities for health and esteem are being taught,” Ms. Bivens-Davis said.

How to get Black women out of the “disproportionately affected” category is not an easy answer, because it’s a multilayered problem, agreed Deborah Levine, deputy executive director of Community Development for the New York City-based non-profit ACRIA (formerly the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America).

What’s needed is culturally competent education for Black women, girls and the Black community, and avoid notions simply dealing with the highest of high risks, she recommended.

“Educate across the board, using all the tools that we have in our prevention tool kit, everything from one-on-one peer education, using people who have been infected and affected by the virus to share their stories, to teaching HIV 101, to helping people better understand the policy implications of things that are happening both in their city and state,” said Ms. Levine.