By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

Dee had been incarcerated in a prison in the Carolinas for more than two decades when he helped organize a national prison strike to end what he called slavery behind prison walls.

Prisoners launched the strike on the 45th anniversary of the Attica Prison Rebellion for Human Rights. In 1971, 1,300 men rebelled against rights abuses and mistreatment at the notorious New York state prison. The standoff between prisoners and guards ended in bloodshed including 43 deaths. The Attica rebellion started Sept. 9, 1971.

Prisoners still live under inhumane conditions today, which is why his organization Jailhouse Lawyers voted to join the strike, Dee said. Dee declined to use his full name and location for fear of reprisals from authorities. He spoke with The Final Call via cell phone.

“I want people to know that we’re not back here just really fighting for us here to receive and be paid these high wages. We’re just saying give the prisoners what they’re due, and mainly also respect our human rights,” he said.

Before ending his job in the prison industry scraping wood to make furniture, Dee said he received $20 every two weeks for a job that otherwise pays $15 to 20 an hour outside of prison.

He’s been punished, like many waging the work stoppage. First, he was sent to a high security unit, then let back into a second tier unit where he was locked down, he said. He’s able to move around a little bit, but his visitation privileges have been stripped.

His canteen and phone privileges have been curtailed.

“It has really cut back on my mobility in this limited environment,” Dee said.

Though he’s been disciplined for not working, Dee doesn’t plan on doing any work again. Prisoners plan to shut down the system again, and take the issue to Washington, D.C., to the president’s doorstep next year, he said.

“In many states, prisoners are not required to be paid a wage at all, and they don’t count as employees, so they don’t get employee protections, social security, or overtime, or any of that kind of stuff,” said Azzurra Crispino of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, a working group of the Industrial Workers of the World.

The prisoners of the Free Alabama Movement, a national movement against mass incarceration and prison slavery, have been hoping for a national strike since 2014, Ms. Crispino said.

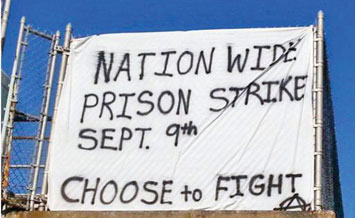

A banner drop in support of the upcoming nationwide prison strike appeared over the Lloyd Expressway in Evansville, Indiana last month.

Once inmates went on strike the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee amplified that call on the outside, she said. There are some things that connect prisoners to a national movement. Prisoners want a fair working wage and an end to long term solitary confinement.

Prison abolition activists believe there would be far less incarceration if inmates received minimum wages with so many companies benefitting from prisoners not being paid.

In addition to eradicating prison slavery, activists want access to health care and rehabilitative programs. They are challenging the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolishes slavery, except as punishment for a crime.

“In Texas, prisoners have to pay $100 to see a doctor, and prisoners across the country are being denied treatment for hepatitis B,” Ms. Crispino said. Some are denied treatment for other ills, like epilepsy.

A prisoner in Wisconsin has been on a more than 100-day hunger strike, and refuses to come out of his cell, so prison staff have been extracting him to force feed him, according to Ms. Crispino. He’s starving to end solitary confinement past a year in Wisconsin.

“The United Nations considers (solitary confinement) torture past 14 days,” said Ms. Crispino.

Organizers noted prisoners’ demands vary from unit to unit and state to state. Many jails and prisons have Alcoholics Anonymous programs, educational programs, and work rehabilitation programs, they said. The whole system is designed to make money off the inmates, activists argued.

Actions in solidarity with the strike outside prisons and jails have occurred in 60 cities and six countries, according to Ms. Crispino.

The actions included noise demonstrations outside county jails in St. Louis where prisoner demands included access to showers, she said.

There were protests at stores that use prison labor, such as McDonalds and AT&T and Starbucks, as well as demonstrations outside of U. S. embassies in Germany, Sweden, Australia and the United Kingdom, she continued.

There definitely has been retaliation for the strike, Ms. Crispino said.

Many strike leaders have been placed in solitary confinement, but never in direct connection to the strike, she said. Prisons always come up with some excuse, she added.

“In Alabama, they’re keeping strike leaders in solitary confinement, but they’ve released violent prisoners out of solitary confinement in the hopes of having more violence occur during the strike, to the point that guards are actually asking for the release of Kinetic Justice (co-founder of the Free Alabama Movement) from solitary confinement so that he can help to keep the strike non-violent as Free Alabama has called for,” Ms. Crispino told The Final Call.

Other official backlash included putting strike leaders in solitary confinement in South Carolina, 100 prisoners in Michigan transferred in an attempt to break that strike, and denial of food in some prisons, she said.

Despite the repercussions, Dee told The Final Call prisoners are preparing for the next phase of the strike. “Many of us are no longer going to cooperate,” he said.

Despite the national mobilization, Dee believes the strike lacked exposure because of prison officials’ tactics.

“What we feel like happened is, of course, the prisoners throughout the country had already been aware this strike was going to take place. We had expected them to move a little bit more faster with mass lockdowns, mass brutality, pressure of the young strike, but what they did was instead, in certain areas, particular in areas like the Carolinas, they began to isolate us,” Dee told The Final Call.

“They began to lock us down in our cells, or they began to immediately transfer us to maximum security units, the ones that they were able to identify,” he said.

Prison officials allowed others who participated, but who weren’t labeled leaders or instigators, to float around without actually bothering them, Dee said.

“I think what they were doing is they had a collective strategy not to lock down as many prisons as they could, because if they locked it down, it would put a spotlight on it, and everybody was waiting on these gigantic lock downs,” Dee continued.

“They were trying to undermine what we were doing and kill the morale as well as the people outside who were in support of what we were actually doing back here,” he said.

Once the spotlight erodes, he feels there will be more retaliation because prisons have to respond with some kind of pressure to ensure strikes don’t happen again, he said.

In some ways, the prisons’ tactics have worked because some prisoners feel the nonviolent approach may be discouraging, Dee opined.

“They want more direct action. We did note in certain prisons where there was direct action, the prisons had to immediately engage and lock down the prisons, and couldn’t go into their usual mode. They could no longer hide,” he explained.

But on a mass level, he said, the tactics haven’t worked.

“We have carefully been monitoring this issue, and we have not gathered any data that the federal inmate population was planning any type of disruption. We did not experience any disruption in our daily operations within our institutions,” Justin Long, a spokesperson for the Federal Bureau of Prisons told the Final Call.

Elaine Brown, former Black Panther Party leader, told The Final Call she didn’t know about the national strike. She does know that if there are prisoners that are refusing to work for free, people have to support them.

She was one among the first supporters of inmates who joined one of the largest prison work stoppages in Georgia, the Georgia Prisoner Strike for Human Rights in 2010.

“The difference between what happened in Georgia on Dec. 9, 2010 is we knew that any announcement of the strike would probably cause it to be shut down,” she said.

Every prisoner had to be involved or the whole action could have been undermined and completely thwarted, she said. There was no public announcement, or power that supports the prison system and part of the prison system would have shut that down right away, Ms. Brown said.

The first day of the strike eight prisons participated, according to Ms. Brown. “It was only supposed to be a one-day strike, and we named the prisons,” she said. “It was them, the prisoners, because it was their lives, and it was their participation that was required,” she told The Final Call.

The prisoners decided to extend the strike, and it lasted eight days, Ms. Brown added.

“The prison wasn’t shut down, and the prison wasn’t taken over. The prisoners refused to work. But it’s incredible when you think about it, by not working, the guards began to beat people up, hose places down, started fires in some prisons,” Ms. Brown said.

“There was just so much reporting on what they did, and we formed the December 9th Coalition to support the prisoners’ rights.”

Everyone considered a leader of that prison work strike in Georgia ended up in the high max unit at Jackson State Prison, including her own adoptive son, “Little B,” according to Ms. Brown.

He’s been in isolation for five years, the first one and a half on 24- hour lock down, she said.

“What these prisoners did was so courageous and what they wanted was so minimal. What they wanted was possible: Better nutrition, better education, other than just a GED … decent health care, the same kinds of demands that came out of Attica, the same kinds of demands that George Jackson raised when he effectively became the head of and launched the prisoner movement, which means prisoners are participating and not people on the outside other than as support– because we’re not in the prisons, so we don’t have to suffer the consequences of what happens. They do,” said Ms. Brown.

Outside supporters should stay in touch with people who are in prisons, because so many have families who can’t afford to go to visit them, she said.

“When people are shut away it’s as if though they might as well have died. It’s like, we’re sorry, and after so long, too bad. We have a general idea. We don’t want to see too many prisons, but in terms of day to day life, most of the men and women in prison are suffering under barbaric circumstances,” she said.