By Charlene Muhammad CHARLENEM

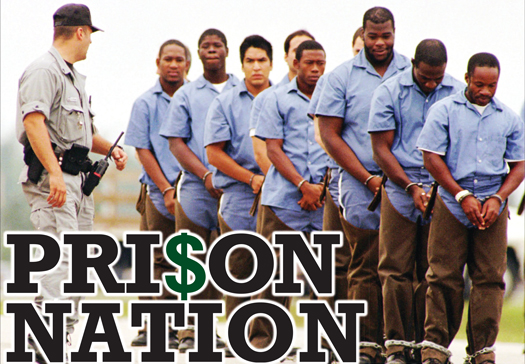

How mass incarceration still feeds lucrative prison industrial complex in U.S.

LOS ANGELES– Prison abolition groups are fighting to cut the tentacles of the prison industrial complex saying that it dehumanizes and exploits inmates largely through private corporations.

Prisoner advocates say the high costs of prisons are fueled by stock trading, prison labor, prison construction, exorbitant phone call fees, and other money made on the backs of the poor.

“The fight to end mass incarceration is immense. This is a country that was founded on a lot of those principles to criminalize and exploit people of color,” said Daniel Carillo, executive director of Enlace.

The alliance of low-wage worker centers, unions, and community organizations in Mexico and in the U.S. organizes for racial and economic justice.

Its National Private Prison Divestment Campaign targets investors in the Corrections Corporation of America and GEO Group, the two largest private prison companies in the United States. Their private prisons are slated for cuts with a Justice Department Aug. 18 announcement that the federal government would phase out use of private prisons.

Mr. Carillo said the Justice Department’s efforts are a step forward, but companies are scrambling to determine what their next steps are for expanding mass incarceration–and making money.

Enlace has been meeting with groups to push for the closure of immigrant detention centers, most of which privatize, he said.

Phone calls, commissary and price gouging

“Over the last couple of decades, this industry has really been created from nothing,” said Carrie Wilkinson, Prison Phone Justice Director for the Human Rights Defense Center.

In this Aug. 14, 2015 photo, Larry Stephney holds wooden products he helped make while he was an inmate at a privately run prison in Nashville, Tenn. Stephney says inmates were required to build plaques, birdhouses, dog beds and cornhole games for officials who sold the items through an online business and at a local fl ea market.Photo: AP Wide World Photos

The whole web of prison for profits grew off the prison phone industry, she said.

“Thirty years ago, prisoners picked up the phone and made a collect call to your family or their loved ones for support and now there’s been an entire industry created with the business model of a company going to a correctional facility and being granted a monopoly contract in exchange for a kickback paid to the correctional facility based off of gross telephone revenues,” Ms. Wilkinson told The Final Call.

Over time, she said, the government has seen an opportunity for profits through prison phone calls. Prison phone rates have long been based on the amount of kickback, which works backwards, she said.

Instead of offering the best service for the lowest price, prison phone contracts include kickbacks of up to 93.6 percent of gross revenues going back to the institutions, she said.

For every dollar spent, almost 94 cents goes to the Arizona Department of Corrections which has a contract with Century Link, observed Ms. Wilkinson.

“The prison phone industry is a billion dollar industry. The last number I saw regarding kickbacks paid nationwide I believe was 2013 and the number was $460 million paid to correctional facilities in a year,” Ms. Wilkinson told The Final Call.

Those kickbacks were generated solely from prisoners and their families, some of the poorest people in the country, unti the Federal Communications Commission stepped in.

Through the 2011 Campaign for Prison Phone Justice, co-founded by the Human Rights Defense Center, activists won rate caps for interstate calls, effective February 2014.

Rates for collect calls were capped at 25 cents a minute and for 21 cents a minute for debit or prepaid calls, said Ms. Wilkinson. That led to a significant increase in call volume since people could afford to make calls, though the rates are still too high, she said.

She stated, “In 2010, a 15- minute call from the Washington Department of Corrections cost $18.30 as one of the highest in the country, and now that same call costs $1.65.”

But companies just took the opportunity to increase in-state call rates after that, she said. And there was also an acceleration in the use of video monitor visits, instead of in-person visits, and money transfer fees to put money on prisoners’ books so they could purchase items from prison commissaries.

The latter presented a dual edged sword with families paying exorbitant fees to transfer funds and prisoners price gouged to buy what should be reasonably priced items, she explained.

With the use of monitors, loved ones must now pay fees to visit with someone who is behind bars as there is a charge to pick up a phone, talk to and see someone on-screen. “What I personally fi nd particularly egregious about the video presentations is that in a number of facilities, the facilities are eliminating in-person visitations altogether, and in some of the contracts I’ve reviewed, the kickbacks paid to the facility is based on volume,” Ms. Wilkinson said.

“I think that we’re now personally affected by mass incarceration. If we don’t have a personal family member who’s incarcerated, we have a friend who has a family member, or we know someone. It’s much more personal to us and we have an opportunity to hear about these things,” she said.

Tax breaks and prison industry

National activists are pushing Congress to eradicate the hundreds of millions of dollars in tax breaks private prison corporations receive under the guise of real estate investments.

According to Bob Sloan, executive director of the Voters Legislative Transparency Project, the problem stems from a last minute settlement brokered in 2012 when the majority Republican Congress threatened to shut down the government over budget debates.

It included an authorization from Congress for federal prison industries to join a program that exempts certified state and local departments of corrections and other eligible entities from normal restrictions on the sale of goods made by prisoners and distributed between states. Typically prison products had to be sold to government or state agencies and sales were limited to the states in which the products were produced.

The Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program lifts some restrictions and permits certifi ed entities to sell such goods to the federal government for more than the previous $10,000 limit.

The program in part was supposed to put inmates in realistic work environments, pay local prevailing wages for similar work, and help inmates gain marketable skills to increase their rehabilitation and employment when released.

But many inmates receive nowhere near prevailing wages, activists argued.

‘Cash cows’ milked by the system?

“It’s really a modern day slavery that causes a burden on the family from something as simple as products in outdated vending machines marked up extremely high, like the cost of an average frozen burrito which is $5-7,” said Ansar Muhammad, a Nation of Islam Western Region Prison Reform minister and co-founder of the H.E.L.P.E.R. Foundation gang intervention and prevention organization.

“Prisoners are cash cows and have been for many, many years,” he stated. He worked in the prison laundry department when locked down.

“I made 15 cents an hour and remember at the end of the month, I was able to get me a Ben & Jerry’s ice cream after that. That was the highlight,” Ansar Muhammad said. “Can you imagine all the inmates that don’t have any family or outside support?” They wound up with nothing.

In 1980, the American Legislative Exchange Council began driving laws benefi tting corporations and privatizing everything associated with prisons, such as inmate bank accounts run by a private bank in Florida, Mr. Sloan told The Final Call.

Every inmate is charged $4 a month, whether money fl ows through his account or not. If he accrues fees over a year and gets $100 all of a sudden, fees are paid right off the top, he explained.

“In 2013, the last count, there were 309 full-time factories operating coast to coast employing over a million inmates and most of those factories are hooked up with these different private companies,” he stated.

Those include potato cultivation, harvesting and distribution by the Idaho Department of Corrections, as well as private medical care by different health care organizations.

“Both Elijah Muhammad and Minister Farrakhan Muhammad have told the world that the Black man and woman are the chosen people of God,” said Nation of Islam Prison Reform Minister Abdullah Muhammad. “Minister Farrakhan said that this is a spiritual problem calling for a spiritual solution.”

Citing scripture, he said, it is prophesied that the people of God would be snared in holes and hid in prison houses. “They are for a prey. The snare is the crack cocaine pipeline to finance a war. The prey are the people of God entrapped and entangled in the distribution and sale of the cocaine which results in mass incarceration,” Min. Abdullah Muhammad said.

“Once snared, the lobbyists go to work on the politicians to pass laws that allow the corporations that they represent to prey on the ensnared to feed their treasuries by providing business opportunities to phone companies, clothing companies, food service, personal hygiene products and cheap labor, etc.,” he continued.

Under the National Correctional Industries Association, prisoners make almost everything from apparel, hardware, chemicals, decals and tags and license plates, eyeglasses, fabrics, furniture, lighting, electronics and entertainment, software, shoes, sewing machines and food products.

“It’s an evil wheel, and in order to stop it, really put a dent in it, we’ve got to get rid of the fodder that they’re using for labor,” Mr. Sloan said.

Reduce incarceration, reduce overcrowded prisons, and get people back on the streets, to their families, and work to not incarcerate people except when they pose serious threats to other humans, he recommended.

“That used to be what it was, a last straw, but it’s moved away from that. Now it’s mandatory minimum sentencing, prison for 10 years. They know you have a shelf life for 10 years, and they’re going to get to utilize them for 10 years,” Mr. Sloan argued.

However, those same people that worked for prisons while incarcerated making chain-link fences for 10 years are rendered unqualified once released.

“They will not hire them, because number one they’ve got to check the box (saying you were convicted of a crime), and number two, why should I hire you at $15 or $20 an hour when the guy that’s replacing you in that factory behind the prison fence we only have to pay him 35 cents an hour?” asked Mr. Sloan.

The big news for 2016 has been reform in the states, according to Molly Gill, director of federal legislative affairs for Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

Florida repealed a mandatory minimum 20 year sentence for aggravated assaults. In some cases, she said, people who’d fi red shots in self-defense were getting charged and sentenced 20 years even though no one was injured.

Maryland repealed all of its mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses earlier this year, and Iowa cut its mandatory minimum drug sentences in half and gave people parole eligibility halfway through their minimum term, Ms. Gill said.

“We’ve seen well over 30 states now that have reformed their mandatory sentencing laws in the last 10 years, and crime has continued to go down in these states, so sentencing reform has been a huge success at state level,” Ms. Gill said.

Part of that stems from strong bipartisan support in Congress, she said. She attributed some of the support to age rather than party lines. Some congressional members age 60-65 lean toward those laws and seem reluctant to reevaluate them, while younger ones, under 60, grew up in a very different world, she noted.

“They weren’t part of passing the mandatory minimums in the fi rst place … they’ve seen crime go down, … Also, frankly, probably a lot of them know people who have substance abuse problems and they’ve seen that these long drug sentences probably haven’t done much to stop the use of drugs,” Ms. Gill added.

Dorsey Nunn is with the All of Us or None Prison Advocacy Organization and executive director of the San Franciscobased Legal Services for Prisoners with Children. The objective of prison privatization is to make money, not to provide real security, he argued.

“When I look at private prisons, that’s one of those places where you could say clearly on the stock exchange, they’re selling and trading human bodies!… They’re trading Latinos and Black people on the Stock Exchange,” he said.