By Saeed Shabazz-Staff Writer-

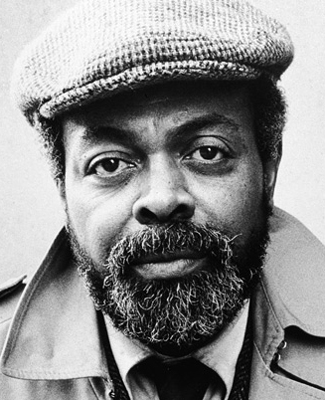

Photo: amiribaraka.com

(FinalCall.com) – Amiri Baraka, 79, born in 1934 in a Newark, N.J. hospital teacher, activist, artist, leader, died on Jan. 9 in a Newark, N.J. hospital. Mr. Baraka, born Everett LeRoi Jones, had been admitted to the Beth Israel Medical Center’s Intensive Care Unit in December.

Mr. Baraka leaves behind his wife Amina Baraka and children Ras Baraka, Lisa Jones, Kellie Jones, Obataj Baraka, Shani Baraka, Dominque DiPrima, Maria Jones, and Amiri Baraka, Jr. He attended Newark’s Barringer High School, Columbia University, The New School, Rutgers University and Howard University.

In 1963, Mr. Baraka published “Blues People: Negro Music in White America,” and in 1964 published a collection of poetry “The Dead Lecturer,” while writing the Obie Award winning play “Dutchman.”

“Amiri Baraka was a literary genius and champion of global and domestic justice,” said Bill Fletcher Jr. in an email while traveling in Palestine. Mr. Fletcher, a writer, activist, and past president of TransAfrica Forum, added, “Had he compromised on his principles the system would certainly have rewarded him. Yet he refused to back down and remained defiant in the face of oppression and injustice.”

“One of our literary giants,” commented Abdul Akbar Muhammad, international representative of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan.

Mr. Baraka definitely made an impact on the struggle for freedom and justice, Min. Muhammad said.

“Even when he changed his positions he stood on principle. He has a tremendous history and a tremendous legacy,” Min. Muhammad said.

“Black nationalist, revolutionary artist, committed Marxist- Leninist, if there was ever anyone whose life represented the deep complexities and dramatic scope of Black activism and resistance, it was Amiri

Baraka. Baraka’s life was the personification of the radical Black tradition,” wrote human rights activist and author Ajamu Baraka.

Amiri Baraka inspired two generations of Africans from the African Diaspora to the African continent to study, organize and uncompromisingly commit to African liberation and global revolutionary transformation, Ajamu Baraka said.

Lawrence Hamm, co-chairman of the Newark-based Peoples Organization for Progress said, “Amiri Baraka was the spirit of revolution–the embodiment of what he talked about– revolutionary transformation. He was the first in the flesh leader that was not just talking about ‘revolutionary transformation’, he lived it, made it work.”

The 1972 National Black Convention took place in Gary, Indiana at Westside High School from March 10 to March 12. The convention brought together a wide spectrum of Black leaders and the grassroots in an effort to create a progressive political agenda for the Black community.

Mr. Hamm recalled the convention as a “transfiguring experience.” After the event he went to Amiri Baraka asking for an African name. “He called me Adhimu Changa, which means ‘exalted youth,’

I was 18 at the time,” Mr. Hamm said.

Min. Muhammad recalled how committed Mr. Baraka was in uniting Black people, and how he collaborated with Min. Farrakhan on getting the convention off the ground. “I loved the brother,” said Min. Muhammad, who recalled that the last time the two spoke was in Harlem at a pro-Libya rally in August 2011.

“Celebrating Amiri Baraka (2003)”

Mr. Hamm said the last time he spoke to Mr. Baraka was perhaps October or November 2013. “We always talked personally, never by phone,” Mr. Hamm said with a chuckle. The Final Call asked Mr. Hamm if Mr. Baraka shared a vision about Blacks struggle going forward. “Up until he fell ill, he talked Black Power. He still saw voting as an important tactic, he continued to advocate voting for progressive candidates. I would believe that is why he encouraged his son Ras to run for mayor of Newark. And I also know that he was still critical of capitalism and imperialism,” Mr. Hamm said.

The most important thing now is that his work be made available to young people, said Min. Muhammad. “I speak to young people and they don’t know who Richard Wright is, and I don’t want that to happen to Amiri Baraka’s work,” he said.

“Amiri Baraka for his work has taken influences from a number of musical orishas such as John Coltrane, Malcolm X, Ornette Coleman and Thelonius Monk which got him regarded as the founder of Black Arts Movement in the era of sixties,” according to the biography on his website.

But the playwright’s work and outspokenness wasn’t confined to yesterday: He was stripped of his title of poet laureate of the state of New Jersey in 2003. His crime was writing the poem, “Somebody Blewup America,” after the World Trade Center attacks. He denied being anti-American or anti-Semitic with the poem. Though the poem dealt with a litany of America’s crimes against people of all races and religions, different eras and different locations, one verse drew ADL attention. “Who knew the World Trade Center was gonna get bombed Who told 4000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers To stay home that day, Why did Sharon stay away?” the poem read. A firestorm of controversy ensued and Mr. Baraka held a public session at a Newark library. He defended his work, refused to be miscast and refused to apologize.