-Guest Columnist-

(FinalCall.com) – Can a Hollywood that is more prone to entertain than to inform do justice in portraying an institutionalized system of brutality, America’s slave trade, that spanned over three centuries?

And what is the responsibility of filmmakers to those whose ancestors suffered horrendous atrocities as slavery was used to fuel and maintain America’s capitalist beginnings?

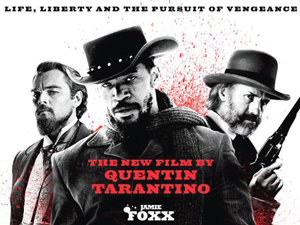

In Quentin Tarantino’s new movie Django Unchained, an homage to Italian director Sergio Leone’s sub-genre of films called “spaghetti westerns,” Jamie Foxx’s character goes on a quest with his mentor turned sidekick, played by Christoph Waltz.

Django, played by Foxx, is on a mission to free his wife who was re-purchased by the owner of a sprawling Mississippi plantation, Calvin Candy, played by Leonardo DiCaprio.

The fact that Django is a spaghetti western with the atrocities of slavery as backdrop speaks to the uneasiness with which this material is presented and gives credence to film director Spike Lee’s criticism of the movie. Lee, who refuses to see the film, said telling the story as a spaghetti western is “disrespectful to my ancestors.” His comment not only reveals the delicate nature of how the movie’s subject matter had to be presented, it also reveals obstacles Tarantino had to overcome to make the material palatable.

To allow the audience to get stuck in a recreation of the actual atrocities of slavery and not offer any relief would defeat the purpose of the film. It is actually a testament to Hollywood’s ability to control the sensibilities of the viewing public and not deal with the actual institution at the root of the movie.

Django’s most important contribution isn’t even in the film, it’s in interviews about the film that bring a discussion about slavery centerstage.

Not only did Tarantino and his cast members do the customary Hollywood movie promotion circuit, they sought out and engaged some Black media outlets in a discourse about slavery.

One particularly revealing exchange during a post-screening discussion of the film, according to Roots New York bureau chief Hillary Crosley, happened when a Black woman interrupted, saying, “A lot of Black people are not going to like this movie.”

Then a few audience members began to heckle Tarantino from the balcony, shouting: “This is bulls—t.”

To Tarantino’s credit he invited his detractors to offer comments. During that exchange, the filmmaker said he recognized the history covered by the movie was “virgin territory.”

“It’s a rough movie,” he said. “As bad as some of the s—t is in this film, a lot worse s—t was going on. This is the nice version.”

Still Tarantino’s willingness to engage his distracters is welcome relief from “Lincoln” director Steven Spielberg’s refusal to have a meaningful discussion about slavery.

Not only hasn’t Spielberg engaged the Black public, he displayed insensitivity by holding a private viewing of a movie about President Abraham Lincoln’s contribution to the ending of slavery, not with the descendents of the recipients of Lincoln’s efforts and the members of the Congressional Black Caucus, but with the all-White U.S. Senate.

His counter argument might be the movie is more synonymous to current political wrangling going in Congress and he wanted to show the Senate how historically bipartisan support for the 13th Amendment–which is the crux of the movie–was achieved.

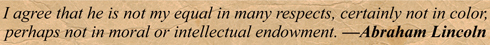

Like Django Unchained the main character’s quest is the focus: Lincoln’s unseen backdrop is the horror of slavery and Blacks’ active contribution to its demise. To display Black people as passive onlookers–as the Lincoln movie does–while this messianic figure towers over the passing of legislation equated with freedom has to be seen for what it is. It is a failure to deal with the reality of slavery and the actual cost of ending it. This wrongheaded approach was eloquently pointed out by Stephen Marche in his blog post on Equire.com. The movie imagines “that American slavery was a matter of debate and policy, that it was a matter of law, and that all white people needed to do was correct their intellectual error of categorizing persons as property.”

Not that the passing of the 13th Amendment wasn’t significant and worthy of the silver screen, but in the context of history, to pretend it was all that mattered and not show Black contributions, not even Frederick Douglas who Lincoln praised and relied upon, is a deliberate lie and a slap in the face of the historical record.

Tarantino and Spielberg’s films also can be viewed in the context of the civil rights movement. To give the main credit of the movement, as many have done, to attorneys that battled in the courts denies the principal contribution made by those in the trenches, who suffered imprisonment, beatings, torture and death, is wrong.

Plus, how many movies has Hollywood made where a Black man–as seen in Django Unchained–encounters and overcomes tremendous obstacles, including capture, and rescues his Black woman?

(Jehron Muhammad, who writes from Philadelphia, can be reached at [email protected].)