CHARLENEM

LOS ANGELES (FinalCall.com) – Seventeen years ago the streets of Los Angeles erupted in pain, tears and violence after an all-White jury acquitted four White police officers of the brutal beating of Black motorist Rodney King. Analysts believe the causes that undergirded the unrest are a long way from being resolved, though some have been addressed.

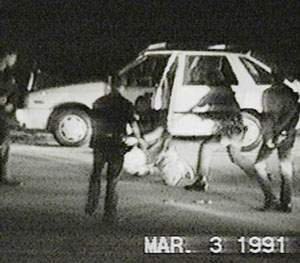

When Mr. King was beaten with batons, kicked and punched after evading police in 1991 on a Southern California highway in his white Hyundai, friction between the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and the Black community was already strained over historical incidents and complaints of racial profiling and police brutality. A bystander’s videotape spread the images around the world and exacerbated tensions.

A year later, on April 29, when the officers were acquitted, focus was placed on the burning buildings, store looting and rioting that ensued which caused 53 deaths, thousands of arrests, $1 billion in damages and 1,000 burned-out buildings. But it also shed light on deeper problems of unemployment, a lack of economic development and other disparities.

Economic factors

Analysts reported that Los Angeles poverty rates in 1990 were at 15 percent. Black males earned 73 percent of the median income of White males, and Latinos, just 47 percent. Last year, the American Community Survey reported that extreme poverty rates in Los Angeles slightly decreased from 15.4 percent to 14.7 percent in 2007.

And economic problems were compounded by the marginalization of Blacks and Latinos in areas of housing, education and public health, the Poverty & Race Research Action Council indicated.

Los Angeles ranked higher than other metropolitan areas in overcrowding, deteriorated physical conditions and financial accessibility of housing. And affordable housing was persistently in short supply, the Council indicated. Further problems included poor access to health care centers, low quality health service, high incidences of chronic illnesses, substance abuse, violence, and schools with inferior resources and less-qualified teachers compared to suburban schools.

Looking back, researchers at The Ralph & Goldy Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies at the UCLA School of Public Policy and Social Research noted that it was easy to see the link between economic forces and the deepening social divisions of the early 1990s, and the association with violence, drugs, gated communities, rapid increase in gangs and the growing isolation of the poor.

Dr. Anthony Asadullah Samad, a syndicated columnist and author, acknowledged several attempts to rebuild Los Angeles and sites that were not in the city in 1992; and, while some economic development has reached into the Crenshaw District in terms of restaurants, charter schools and a few strip mall plazas, he said those few things that have been done are not in sufficient numbers to really make the necessary impact.

“It’s like a man being in a desert asking for a drink of water and you give him not even a half a glass, just a couple of drops. If economic development is not done according to an economy’s scale then it uplifts a few but it’s as if you’re saying you brought 500 jobs to Los Angeles for summer jobs for youth when there’s 20,000 out of work,” Dr. Samad said.

The community should slowly build its economy in terms of making its own clothes, growing its own food, in addition to maintaining its barbershops and bookstores to not only help its psychological state of mind, but also help put pride of ownership in its youth, he said.

Improvements in Community-Police Relations

“We have become more aware of the policies of the LAPD of 17 years ago, even though we still have a significant racial profiling issue. Even though we still have an occasional abuse case that comes up, abuse is not as widespread and as far reaching as it was in 1992,” said Dr. Samad. He said the community also gained a different kind of oversight with respect to how it deals with law enforcement.

According to LAPD Commander Kyle Jackson, the riots forced the department and city government to take a look within, both bureaucratically and politically.

“We had gone off for so many years in the Los Angeles Police Department and the city believing that we were the answer to all of the issues that related to crime, fear and public disorder here in the city. We believed that we could control all of that and I’d like to think we pretty much in a sense were kind of full of ourselves. We were not sensitive to the crying needs of the community relative to listening to what the community felt and believed and needed,” he said.

Commander Jackson added, “We were more in that professional model of this is what you need. This is how you’re going to do it, whether you like it or not in terms of our methodology. This is how we’re going to deliver it, and the Rodney King incident, the ’92 riots, was a manifestation of that.”

The situation was good from the standpoint that it also caused the department to analyze its use of force policy; required more accountability of command officers, watch commanders and supervisors; and it required more training, Commander Jackson told The Final Call.

Marqueece Harris-Dawson, executive director of the Community Coalition, said, “While police abuse is still a concern, and there have been far too many police shootings over the last couple of years, the leadership at the top of LAPD and Chief William Bratton are far less incendiary than Darryl Gates (former police chief) ever was or ever could hope to be and I think that that helps make the situation a little bit less volatile.”

He also noted that while violence as a whole has dropped, it is still very high in South L.A., about double for the rest of the city, and at the epicenter of the civil unrest, conditions around crime and violence really have not changed in a way that it can be deeply felt.