- End police brutality and mob attacks (FCN, 12-11-2007)

- Sean Bell: Tip of iceberg in NYC police murder culture (FCN, 04-16-2007)

- Black men targeted for slaughter: The murder of Sean Bell (FCN, 12-13-2006)

NEW YORK (FinalCall.com) – A year after a deadly police shooting ignited community anger and raised questions about police conduct, activists, elected officials and the family of Sean Bell honored his memory and continued their appeal for justice.

Mr. Bell and two friends were victims of 50 shots fired by undercover police officers after leaving his bachelor party on Nov. 25, 2006.

Three officers indicted for the shooting —Michael Oliver and Gescard Isnora, who have pleaded not guilty to manslaughter and Marc Cooper, who pleaded not guilty to reckless endangerment–are scheduled to go on trial in February.

Police union officials and defense attorneys have said the officers believed Mr. Bell and his companions were headed to his car to retrieve a gun. No weapons were found at the scene.

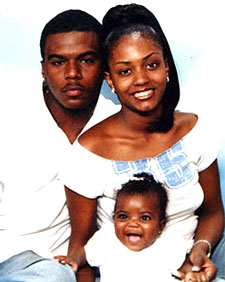

“I want justice,” said Nicole Paultre Bell, the mother of Mr. Bell’s two young daughters, ages four and one, who legally took his name after his death. “I just keep asking myself, ‘Why does this have to be my children? Why me? Why do we have to be the ones to go through this?’ ” she told reporters.

“A lot of people felt that a year would temper the outrage,” Rev. Sharpton told the press, as hundreds gathered at the scene of the shooting in Queens. He vowed to stand with the family until it gets justice. The shooting sparked several protest marches, the largest led by the Rev. Sharpton and his National Action Network wound down New York city’s famed Fifth Avenue shortly before Christmas in 2006. Many demonstrators saw the shooting as symbolic of excessive force against Blacks in New York City.

This year activists called for Blacks to stay away from traditional shopping the day after Thanksgiving to add economic pressure to the demand for justice.

After pressure from the New York City Council, the New York Police Department commissioned the RAND Corp., a think tank, to look for ways to reduce the risk of “reflexive” or “contagious” shooting by its officers.

A week before the one-year anniversary of the Bell killing, however, NYPD officers in Brooklyn fired 20 shots at 18-year-old Khiel Coppin, who had been diagnosed with a mental condition, hitting him at least 13 times. He died at the scene.

New York City Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum told reporters after the fifth and final hearing of a panel created after Mr. Bell’s shooting, known as the Tri-Level Legislative Task Force on Police Procedures, that “something is terribly wrong” with the way police conduct themselves.

“There’s a lack of kindness,” she said. Ms. Gotbaum’s daughter-in-law died in September while in police custody at Phoenix International Airport.

The panel, which includes state, city and federal elected officials, held its first hearing in January and concluded its work on the first anniversary of the shooting.

Ms. Gotbaum admitted the Bell shooting hit closer to home after her daughter-in-law’s death. “I was always interested in the panel, and I was interested in the issue because I represented people who have been affected by bad police behavior,” she said at the hearing, according to media reports.

The NYPD continues to argue it’s statistics show that officers are more restrained these days, claiming officers fired 540 shots in 2006, down 13 percent from 616 shots in 2005. In 1996, the total was 1,292 shots fired. The NYPD also reports nine people were killed by officers so far in 2007. In 2006, there were 13 fatal shootings, up from nine in 2005. In 1996, there were 30 deaths at the hands of police, according to the Associated Press.

A Quinnipiac university poll, taken after the killing of Khiel Coppin, showed 55 percent of New Yorkers approved of the way Police Commissioner Ray Kelly is performing his duties, 30 percent said they disapproved and 16 percent were undecided.

His approval rating was 52 percent after the killing of Sean Bell. Whites favor Mr. Kelly, with 70 percent saying they thought he was doing a good job, compared with 42 percent of Blacks and 36 percent of Latinos.

Police shootings aren’t the only target of community anger and scrutiny. Another reason the police department commissioned the RAND report was to counter complaints by Blacks and Latinos that NYPD’s stop and frisk policy was racist. Blacks comprised 53 percent of those stopped, 29 percent were Latinos and 11 percent White. More than 500,000 people were stopped for questioning in 2006, according to police department statistics.

While the study acknowledged that Blacks were stopped at a rate 50 percent greater than their representation in the census, RAND argued that using the census as a benchmark was unreliable because it didn’t factor in higher arrest rates. Critics say that 90 percent of those stops in 2006 did not lead to an arrest. RAND also argued that NYPD’s tactics were race-neutral.

The National Latino Officers Association of America told reporters the “study is comprised of endless excuses, and statistical justifications.”

“The report draws conclusions that have no basis in reality. If left unchallenged, it is the justification for racial profiling, abuse and discrimination,” said Anthony Miranda, a retired NYPD sergeant, and executive chairman of the National Latino Officers Association.