JIM.LOBE

- U.S. conduct in ‘terror war’ destroyed image abroad (FCN, 07-17-2006)

- Neo-con fanatics push internment for American Muslims (FCN, 02-18-2005)

- The “War on Terror Exposed” (FCN/Min. Louis Farrakhan, 05-03-2004)

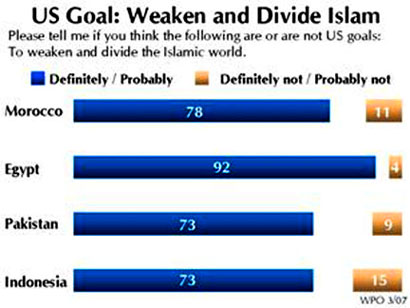

WASHINGTON, U.S.A. (IPS/GIN) – More than 75 percent of people in Egypt, Morocco, Indonesia and Pakistan believe U.S. foreign policy is aimed to weaken the Islamic world and maintain control over oil in the Middle East, according to a survey released in April.

Conducted by the University of Maryland and WorldPublicOpinion.org, the detailed survey suggests that Muslims abroad remain suspicious of U.S. motives, six and a half years after U.S. President George W. Bush launched his “global war on terror.”

An average of two out of three respondents named “expand(ing) the geographic borders of Israel” as a third major U.S. policy objective in the region. Dividing the Islamic world and controlling oil were seen as the Bush administration’s top two objectives. By contrast, less than one in four agreed that Washington wanted to create “an independent and economically viable Palestinian state,” despite Pres. Bush’s explicit endorsement of that goal since before the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.

Sixty-four (64) percent of respondents in Indonesia, Pakistan, and Morocco said another U.S. goal was to “spread Christianity in the region.” The question was not asked in Egypt.

“While U.S. leaders may frame the conflict as a war on terrorism, people in the Islamic world clearly perceive the U.S. as being at war with Islam,” said WorldPublicOpinion.org editor Steven Kull, who also directs the University of Maryland Program on International Policy Attitudes. “There’s a feeling of being under siege.”

Suspicion of U.S. goals was particularly high in Egypt, which is by far the largest recipient of U.S. aid in the Islamic world. Egypt has been receiving high levels of aid since it signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1978. Respondents were also suspicious in Morocco, another long-time U.S. ally.

Respondents in Indonesia and Pakistan were generally less suspicious of U.S. motives, although large percentages of Pakistanis–40 percent or more–declined to answer many of the more than 50 questions included in the survey, in part because respondents in rural parts of the country often said they did not know enough to voice an opinion.

The survey, which was based on personal interviews of 1,000 or more respondents in each of the four countries, also found widespread sympathy for what they said they believe are key goals of al-Qaeda and other violent Islamist groups.

Nearly three out of four respondents said they agreed with al-Qaeda’s goal–if not its means–of forcing Washington to remove its bases and military forces from all Islamic countries and stop favoring Israel in its conflict with the Palestinians. They also agreed with al-Qaeda’s ambition “to stand up to America and affirm the dignity of the Islamic people” and “to keep Western values out of Islamic countries.”

Respondents showed somewhat less enthusiasm for al-Qaeda’s more religiously oriented goals, such as enforcing strict Sharia law in Muslim countries or establishing a single state, or Caliphate, throughout the Islamic world. However, these goals also commanded strong majority support, particularly in Morocco.

At the same time, majorities in each country–ranging from 56 percent in Pakistan to 82 percent in Egypt–said they thought global economic globalization and communications was positive for their country. Similar support was found for democratic forms of governance.

The survey, which was carried out between mid-December and mid-February, is the latest in a string of polls suggesting that Washington’s image in the Islamic world, particularly in Arab countries, has fallen to all-time lows.

In a survey carried out late last year by the polling firm Zogby International in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia and released in February by University of Maryland professor Shibley Telhami, three out of four respondents described their attitudes toward Washington as either “somewhat” (21 percent) or “very” (57 percent) unfavorable. The same poll found that Pres. Bush himself was by far the Arab world’s most-disliked world leader, exceeding even Israeli leaders who had topped four consecutive annual surveys carried out by Zogby and Prof. Telhami since 2002.

Asked their opinions of the current U.S. government in the latest poll, a majority of respondents–ranging from 59 percent in Pakistan to 93 percent in Egypt–said their views were unfavorable. Substantially smaller majorities–just more than 50 percent–expressed unfavorable views of “the American people” in Egypt, Pakistan, and Indonesia, while two out of three Moroccan respondents said their views of the people of the United States were favorable.

In addition to identifying what they thought were major U.S. objectives in the Middle East, respondents were asked to choose among three possible options for what was “the primary goal” of the U.S. war on terrorism.

Strong majorities in Pakistan (68 percent), Morocco (72 percent) and Egypt (86 percent) chose either “weakening and dividing the Islamic religion and its people” or “achieving political and military domination to control Middle East resources.” An average of only 13 percent of respondents in the same three countries said the primary U.S. goal was to “protect itself from terrorist attacks.”

The results in Indonesia were somewhat less negative. Fifty-three percent of respondents chose one of the first two options, while 23 percent selected the third. Prof. Telhami noted that such findings were typical of recent surveys.

The United States was also perceived in all four countries as having an extraordinary amount of control over events in the world. Nearly nine out of 10 Egyptians said the U.S. exercises control over “most” (32 percent) or “nearly all” (57 percent) “of what happens in the world today.” An average of nearly two out of three respondents in the other three countries agreed with those assessments.

The survey found more ambiguous responses to questions about al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. Small pluralities in Egypt (40 percent), and Pakistan and Morocco (27 percent) said they had generally “positive” impressions of him, as opposed to “mixed” or “negative” views. In Indonesia, views were more evenly split.

The apparent inconsistency between those findings and strong disapproval of attacks on civilians may be explained in part by uncertainty over al-Qaeda’s role in the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York and the Pentagon in Washington. Across the four countries, an average of 42 percent of respondents said they didn’t know (63 percent in Pakistan) who was responsible for the attacks.

Only 2 percent of Pakistanis believed that al-Qaeda was responsible for the attacks, compared to 34 percent who said they believed the U.S. government or Israel was behind them.

Christine Fair, a South Asia specialist at the U.S. Institute of Peace, said the results may reflect confusion about the group’s leaders who “20 years ago were ‘freedom fighters,’ and now they’re ‘terrorists.’ Folks just don’t believe al-Qaeda did this.”

Opinions were more evenly divided in the other three countries: In Morocco, 35 percent named al-Qaeda, while 31 percent said either the U.S. or Israel; in Egypt, the breakdown was 28 percent and 38 percent, respectively. In Indonesia, 26 percent of respondents blamed al-Qaeda, while 20 percent said they believed the U.S. or Israel was responsible.