JIM.LOBE

WASHINGTON (IPS/GIN) – Amid growing violence in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, the United States announced Oct. 19 it will consider requests to sell weapons to the country’s interim government on a case-by-case basis, signaling the end to a 13-year arms embargo.

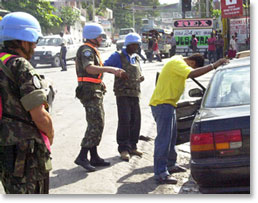

The decision, confirmed by the State Department, appears designed to begin supplying weapons to the 2,500-man police force that has carried out gun battles with militants loyal to ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who was flown by the U.S. into exile earlier this year.

The police, however, have also been accused of firing on peaceful pro-Aristide demonstrators and rounding up well-known leaders of Aristide’s political movement, Lavalas.

Human rights group Amnesty International (AI) denounced the recent arrest of Reverend Gerard Jean-Juste while the priest was distributing food to hundreds of children and poor people at a church in a Port-au-Prince suburb.

According to testimony gathered by the London-based group, Rev. Jean-Juste was punched while being dragged out of the presbytery by police officers, some of whom were wearing masks.

The police later said the arrest was a pre-emptive action based on intelligence that the priest was linked to pro-Aristide groups, although no evidence to support that charge has been released.

“Amnesty International considers that, if the arrest is politically motivated for Rev. Jean-Juste being a vocal supporter of former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Amnesty International would consider him a prisoner of conscience,” said the organization in a statement.

The rise in tensions in the Caribbean nation began in September after Hurricane Jeanne devastated the port town of Gonaives, Haiti’s third-largest city, killing as many as 2,000 people and destroying hundreds of homes and businesses.

The interim government of Prime Minister Gerard Latortue, which took power with the help of U.S. Marines and French troops after Mr. Aristide’s ouster, failed to coordinate or provide much help to the stranded population, fueling popular discontent with the regime, particularly among the poorest sectors that have long supported Mr. Aristide.

Pro-Aristide demonstrations broke out on Sept. 30, the 13th anniversary of the military coup that exiled the leader the first time in 1991. Mr. Aristide, the first democratically elected president in Haiti’s history, is now living in South Africa.

At least two protestors were killed by police Sept. 30. The following day, the remains of three policemen who had been beheaded were found on the street, bringing tensions in the capital to a boil. Some 50 people have since been killed in sporadic violence.

Since the anniversary, the situation in the capital has been unsettled, while former soldiers and military officers who led an insurrection against Mr. Aristide last winter and who still control much of the countryside, announced they intend to move to the capital to back the police against pro-Aristide militants. The former soldiers have pressed the government to restore the army, which was abolished by Mr. Aristide after his return from exile in 1994.

The result is a growing sense of chaos in Haiti, according to Professor Robert Fatton, a Haiti expert at the University of Virginia, who described the situation as “very explosive.”

“What’s going on now is that the Latortue government is losing control of the situation,” he said in an interview.

The UN force, which took over from U.S. and French forces in July, is currently only at less than half strength.

But Prof. Fatton said neither more troops nor renewed U.S. aid to the police is likely to resolve the situation, particularly given the failure of the government to take a more conciliatory attitude toward Lavalas, which most observers believe remains the most popular political movement in the country.

“The UN could send more troops, but that’s not really the problem,” he said. “There has to be some sort of real, meaningful dialogue between the different sectors in Haiti, particularly Lavalas. The growing and very explosive polarisation, with the former army entering the scene and the government lacking the means or the will to curb it, spells big trouble.”

He also accused the government of using Aristide as a scapegoat for its own failures.

“They want to portray him as completely unpopular and yet blame him for paralysing Port-au-Prince; they’re trying to find a way to explain that the country is falling apart and they are not responsible, so they arrest Lavalas leaders, some of whom could not possibly be involved with violence.”

Washington imposed an arms embargo against Haiti after the coup against Mr. Aristide in 1991, although it helped equip and train the police force created after the United States restored him to power in 1994.