By Richard Muhammad

Straightwords e-zine

CHICAGO (FinalCall.com) – Ex-offenders are usually depicted as lazy, angry malcontents, always willing to blame someone else for their troubles.

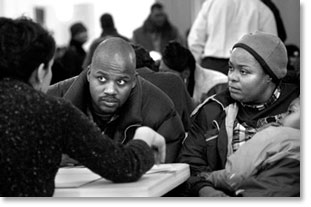

But when Rep. Danny Davis (D-Ill.) held a recent all-day summit that dealt with cleaning up criminal records and offered services for ex-cons, the stories told expressed desires that were anything but angry, blame-shifting. Voices often broke with frustration, layered over a steely determination to move forward.

The problem is the system doesn’t make moving on very easy.

“You pay your dues or whatever and they still got this thing hanging over your head. It’s like they’re still punishing you,” said Jerome Bolden, standing outside Mt. Pisgah Missionary Baptist Church on the Southside of Chicago.

The crowded sidewalk was covered with ice and snow. A brisk wind whipped up and down the block. Several thousand people gathered inside for expungement information, meetings with lawyers, AIDS tests, jobs, community support and state service agencies, as well as coffee, donuts, chicken and french fries. Others gathered on the church steps, in doorways and on the sidewalk.

Bolden, a 30-year-old from the near west side, was bundled up against the cold and wore a dark red, knitted skullcap with a Temple University logo. His feelings about the summit were mixed.

Like many of the 3,000 who showed up for the Saturday meeting, he is a convicted felon. The draw for the meeting was expungment, or clearing of criminal records. Bolden discovered he was ineligible for expungement.

As a felon it will take a petition to the Illinois Prison Review Board, hearings before judges and a reprieve from Gov. Rod Blagojevich, to get a nearly 10-year-old drug conviction off his record.

“Don’t nobody want to be out here, in the cold, selling no dope, or having to rob and kill and do all that stuff,” said Bolden. “But what can you do when society wants to keep you out of the mainstream?”

Bolden is one of the lucky ones. He has a B.A. in sociology with an emphasis in criminology from Northern Illinois University. A few credits shy of his master’s degree, Bolden is an outreach counselor for a program that services mentally ill people and substance abusers.

Bolden has lost jobs because of his prior record. He said the temptation to try to make a quick buck and survival instincts are real. People have to eat and take care of families, he points out. Bolden doesn’t have children, but does have a supportive family, and is committed to helping the community. He hasn’t had any run-ins with the law, but feels the stigma of having a criminal conviction.

Do the time, still pay

for the crime?

Laws passed by Illinois politicians, other state legislatures and federal legislators have made seeking a fresh start harder. A few examples:

– In the land of Lincoln, ex-felons were barred from getting licenses to work as barbers or cosmetologists and other Illinois professions. Some of the restrictions were changed last year, but significant barriers remain.

– In Florida and seven other states, felons lose the right to vote permanently. One in four Black men in Florida cannot vote because of felony convictions.

– Federal law prohibits felony drug offenders from receiving public aid, public housing and grants to go college.

– Forty-two states are enforcing a lifetime welfare ban for federal felony convictions for drug use or sales in full or in part. Twenty-two states enacted the ban without any modification, such as reinstatement after one-year of ineligibility, or passing regular drug tests.

“How can society tell me that they let me go and tell me to reintegrate myself into society but they won’t give me a chance to go to school and better myself, or they won’t give me a chance to get a job?” asked Christopher Buford, 32, who made the 40-minute trip to Mt. Pisgah from Naperville, Ill., with his wife. “If 5,000 people showed up here today, that means that it’s 5,000 people that want to be helped. Now where is the help at?”

According to Marc Mauer of the Washington, D.C.-based Sentencing Project, about $40 billion is spent on corrections across the country. A small fraction goes to helping inmates or ex-offenders, he said.

Record numbers of individuals locked up during the 1980s and 1990s are coming home, Mr. Maurer said. Since 1998, about 600,000 people have been released from prison every year, about 1,600 people a day, the Sentencing Project reports. In 1998, Blacks accounted for 44 percent of all re-returning prisoners, the group said.

Lawmakers “are increasingly raising the bar and making it more difficult to complete the reentry process,” said Mr. Mauer. In 1994, Congress outlawed federal education grants to inmates pursuing higher education while incarcerated, he said. “It amounted to less than one percent of the Pell Grant money, but it was mean-spirited and sent a signal.”

In his Jan. 20 State of the Union Address, President George Bush proposed a four-year, $300 million Prisoner Re-Entry Initiative to expand job training and placement services, to provide transitional housing, and help newly released prisoners get mentoring, including from faith-based groups.

“We know from long experience that if they can’t find work, or a home, or help, they are much more likely to commit more crimes and return to prison,” said Pres. Bush. “America is the land of the second chance–and when the gates of the prison open, the path ahead should lead to a better life.”

Ryan King, a research associate with the Sentencing Project, was heartened by the president’s remarks and hopes the administration will fight for funding of the program within the Department of Justice budget. Over the past couple years, the White House has put $100 million into the Justice Department’s “Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative,” he noted. The additional money President Bush proposed would likely go into that program, which provides grants for services to ex-offenders, he explained.

People can change

“The reason everybody is assembled here today is because they want to change. They have walked that walk to change their lives. But our government is hindering us. Our elected officials are placating, along with the government, to make sure we continue to suffer,” said Joseph Watkins, of VOTE (Voice Of The Ex-Offender). Mr. Watkins and other VOTE members stood outside the church, circulating a petition to change laws that unnecessarily keep ex-cons from getting jobs.

He felt the summit was somewhat misleading given that many who had felony convictions and are ineligible for expungement. His 25-month-old group wants ex-offenders included in decision-making about what should happen to them.

“It’s not easy having a (criminal) background trying to find a job, knowing that people are going to give you the runaround and tell you, ‘No, you can’t have a job because you got this, that and the other,'” said Tamika Foster, 26-year-old married mother of two children, from South Holland, Ill., a suburb south of Chicago. She got a felony theft conviction at age 20, was never in trouble before and hasn’t been in trouble since.

“No one asks, ‘Did you mean it? Are you remorseful about it?’ Yes, I’m remorseful about it. If I could go back and change the fact that I did it, I would. But I can’t. I learned from my mistake and now I want somebody to accept that I learned from my mistake and give me a chance.”

She hasn’t worked in three years, but has completed two years of probation and 120 hours of community service. The strain is evident in her voice as she waits in line to see an attorney.

Rep. Davis has hosted three expungement summits over the past two years. The first two meetings drew about 1,500 people each and the gathering at Mt. Pisgah drew double the previous numbers. The increase “reinforces the enormity of the problem and complexity of the problem,” said Rep. Davis. He calls it “a fight on all fronts.”

In Illinois, he works with state Rep. Constance Howard, who is pushing state legislation to change laws that govern what crimes and arrests can be removed from records. Rep. Davis helps local constituents get their records cleaned up. After the earlier summits, about 600 people came by to say their records had been cleared. At Mt. Pisgah, Rep. Davis had the head of the Illinois Parole Board on hand to talk to people. The former Chicago alderman has testified before the board himself and said others on the board are willing to give cases a fair hearing.

Rep. Davis is pushing for a federal initiative to help reverse the flagging fortunes of Black men. His other legislation would create 100,000 units of single- room occupancy housing for ex-offenders tied to services. He also supports treatment on demand for convicted drug users.

“It’s gaining momentum, it’s increasing in recognition. Yes, it’s slow. Yes, people are frustrated. But then there are those who step up today and say ‘I got mine expunged. I got me a job,'” said Rep. Davis.

Chicagoan Angela McClellan, 37, appreciated Rep. Davis’ summit, though it won’t help her. She has seven felony convictions and has been to the penitentiary five times.

“We have to recognize that, if the laws don’t change, nothing changes. If there were people doing this thing here today that could automatically replace the stuff on your background, that’s what would happen. But these people’s hands are tied because the laws need to be changed,” she said.