NEW YORK (FinalCall.com) – There are several political science analysts, such as Dr. Manning Marable and Dr. Chuck Stone, and Black historians, such as Dr. Leonard Jeffries, who talk of the “institutionalization” of the Black Agenda.

They also highlight how Harlem’s first Congressman, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., embodied the spirit and discipline of the movement put in place by leaders such as W.E.B. DuBois, with his five Pan-African Congresses; Nat Turner and his slave rebellions; the Honorable Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association; and the Honorable Elijah Muhammad with the Nation of Islam.

Before introducing their opinions on how Adam Clayton Powell Jr. rose from being a Harlem preacher’s son to gaining worldwide recognition as the quintessential Black politician, we must first talk of the environment that created the need for such a man.

“Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was the equivalent of the rap group Public Enemy, the protest politician Jesse Jackson, and the Congressional Black Caucus–all in one,” writes New York-based freelance journalist Tony Chapelle in an article for The Black Collegian Online, entitled “Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Black Power Between Heaven and Hell.”

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was born in New Haven, Connecticut on November 27, 1908. He died in 1972 at the age of 63 from prostrate cancer. His father, Adam Clayton Powell Sr., became the pastor of Harlem’s famed Abyssian Baptist Church in 1908. The elder Powell was born in Franklin, Virginia in 1865. He was the son of slaves, who was raised on a diet of activism. The senior Powell established the social/political atmosphere through the church that was carried on by Adam Jr.

In 1941, Adam Jr. became the first Black elected to the New York City Council. Harlem sent him to Congress in 1944 where he served 11 consecutive terms in the House of Representatives. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. joined Chicago’s William Dawson as the only two Blacks in the House of Representatives, and he immediately challenged the informal regulations forbidding Black representatives from using Capitol Hill facilities.

“I take the view that equality is equality … and that I am a member of Congress as good as anybody else,” Congressman Powell said.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. developed a formidable public following in Harlem through his crusades for jobs and housing. One of his crowning achievements, according to his many biographers, was his leading of boycotts against stores on 125th Street because of their job discrimination.

“Adam could call a rally to picket a dozen stores on any given day,” Ed Fordham, a noted Harlem attorney and community activist, told The Final Call. “He set the tone for the Black community not only in Harlem, but also nationally,” Mr. Fordham stressed.

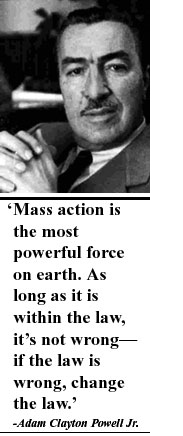

“Mass action is the most powerful force on earth,” Mr. Powell once said, adding, “As long as it is within the law, it’s not wrong–if the law is wrong, change the law.” According to analysts, he landed in Washington armed with a mandate from the grassroots to make a difference.

Mr. Powell would steer some 50 bills through Congress. In 1960, he became chairman of the powerful House Education and Labor Committee, where he orchestrated passage of the backbone of President John Kennedy’s “New Freedom” legislation. He would also become instrumental in the passage of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” social programs.

“He also ripped Congress for allowing lynching of Black men to continue. He challenged the Southern practice of charging Blacks a ‘poll tax’ to vote, and stopped racist congressmen from saying the word ‘nigger’ in sessions of Congress,” Mr. Chapelle noted in his article.

“Adam Clayton Powell Jr. had values,” argues Dr. Leonard Jeffries, professor of Black Studies at New York’s City University in Harlem. He understood that the highest principle he could achieve through politics was to use it as a formidable tool in the struggle of his people in winning freedom in a racist society, Dr. Jeffries said.

“I do not do any more than any other member of Congress, but through the Grace of God, I’ll do no less,” Congressman Powell stressed during a press conference on February 20, 1963.

To understand the political dynamic of Adam Powell Jr., one must analyze the events which shaped grassroots political thought from 1945 to 1995, in what Dr. Jeffries argues was “the most important 50 years for ‘Black Power’ and the ‘Black Agenda’ in America. He explained that the United Nations was being formed in San Francisco in 1945, while Black men–W.E.B. DuBois, George Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, Paul Robeson, Nnandi Azikiwe, Raf Makonnon, C.L.R. James and Jomo Kenyatta, to name a few–were meeting in Manchester, England, to discuss restoring Africa to its place in the world, and to develop a greater understanding of Black political power internationally.

In the book “The 1945 Pan-African Congress and Its Aftermath,” Simon Katzenellenbogm states: “The conference demanded an end to colonial rule and an end to racial discrimination, also a mandate to agitate for a broader struggle against imperialism, for human rights, equality and economic opportunity.” Dr. Jeffries said they went to England to put in place a Black Agenda. He called it a “sacred mission.”

In 1905, through the Niagara Movement, Blacks were urged to protest against the curtailment of their political rights. “A group of liberal Black intellectuals and professionals led by W.E.B. DuBois created an agenda that called on Congress to enforce the Constitution,” Dr. Marable said.

In an article written in 2002 entitled “The Limits of Integration,” Dr. Marable talks about the failure of that movement to put forth the Black Agenda: “From Frederick Douglass to Martin Luther King, Jr.–for more than a century–the dominant political perspective within the Black Freedom Movement was intergrationalist.”

Dr. Marable continued, “In the historical sense; the reactionary wing of the Black political elite has stopped being Black in terms of its historical function as an oppositional group against racism.”

“From each generation, there is an obligation to contribute to the forward march of humanity. The mission for Black people, in this regard, is greater than politics,” Dr. Jeffries stressed. He said when Adam Clayton Powell Jr. marched down 125th Street for jobs in the stores where Blacks spent their money, he was continuing the tradition started in 1644, in New Amsterdam, when Blacks petitioned the Dutch for their freedom, and once gaining freedom, building their own institutions.

“Adam was a logical successor to W.E.B. DuBois–not Booker T. Washington,” offered political scientist and respected author Dr. Chuck Stone to The Final Call. Dr. Stone is a former chief administrative assistant to Congressman Powell who now serves as a Walter Spearman Lecturer, a chaired-professor at The University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Congressman Powell knew his place in history, stressed Dr. Stone.

“Adam was stimulated by Malcolm X; he studied the way he galvanized the people of Harlem,” Dr. Stone said. “Adam appeared in 1956 in Harlem, with Malcolm X and Kwame Nkrumah,” Dr. Stone added. He was very much tied into the Black experience, Dr. Stone said, adding, “We were empowered through Adam.”

“As chronic as the treatment of African Americans has been in the nation, the cry for internationalism has been as consistent. It is what got Malcolm and Martin killed; Robeson blacklisted; Garvey deported and DuBois’ right to travel revoked,” writes Peter Hardie for the BlackCommentator.com. Mr. Hardie is the vice president for Campaign and Labor Affairs for the TransAfrica Forum, a Black think-tank based in Washington, D.C.

“Our historic connection to the cause of African liberation and the linkage of our leaders to the leaders on that continent helped us as a political force in the U.S.,” Mr. Hardie added.

Dr. Marable says that Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was a theological succession of Black leaders, who had a moral commitment to the Black community.

(This is the second article in a series taking a look at Black politics. Next week, “What Went Wrong in Black Electoral Politics: From Powell to the 21st Century.”)

Black politics in America: Before the Mayflower, Reconstruction and after WWII (FinalCall.com)