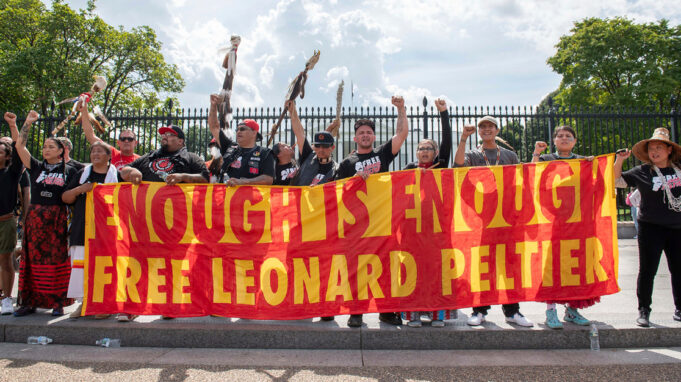

Native American and Indigenous rights activists, people of goodwill, and the family of Leonard Peltier, 79, the longest-held Indigenous American political prisoner in U.S. history, expressed their collective dismay and sadness over the United States Parole Commission’s (USPC) July 2 decision to deny the compassionate release of the ailing American Indian Movement activist.

Mr. Peltier has been imprisoned for nearly 50 years, for the deaths of two federal agents on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in 1973.

“This fight is not over until it is over,” lead Attorney Jenipher Jones and Attorney Moira Meltzer-Cohen said in a news statement e-mailed to The Final Call by the Leonard Peltier Official Ad Hoc Committee, following the commission’s decision denying him parole, which the two lawyers described as grotesque and unconstitutional.

The attorneys are leading the administrative appeal and litigation efforts on Mr. Peltier’s behalf. They said evidence of his guilt was dubious at best and at worse, unjustly manufactured, to secure his conviction [see The Final Call Vol. 43 No.38].

“In a moment of bitter irony, as the nation heads into the 4th of July Independence Day holiday, the United States Parole Commission failed to recommend Leonard Peltier, who is the longest-serving Indigenous political prisoner in the United States, for release,” the attorneys’ statement said.

“The USPC’s July 2 decision continues to impose upon Mr. Peltier a slow Death by Incarceration,” Attys. Jones and Meltzer-Cohen continued.

“The Parole Commission’s decision only illustrates the truth of the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention report, stating that Leonard’s incarceration constitutes an arbitrary detention and noting his parole hearings as a key contributing factor to what they have characterized as his unjustly prolonged incarceration.”

Stating that Congress mandated the closure of the U.S. Parole Commission in 1987, they said it remains in operation because of decades of reauthorizations and extensions causing many elderly prisoners in federal custody to remain locked down and become known as “old law prisoners,” such as Leonard Peltier and many others who are also described as political prisoners in the United States.

“Leonard is a prisoner of war,” his attorneys said.

“We who believe in freedom cannot rest,” Jones and Meltzer-Cohen said, concluding their press statement with a challenge to the public. “We will not give up the fight for Leonard — and neither should you.”

An intensifying universal cry for justice

According to Inforum.com, the case of armed conflict on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the early 1970s brought international attention to the plight of America’s Indigenous people and questions about the American government’s willingness and ability to overcome centuries of inherent racial bias in its justice system.

“In Fargo, hopes were running high that Peltier would be released to return home to the nearby Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and see his family again,” the July 2 news article said of the high hopes many held before the disappointing news from the federal prison in Florida where the Native American elder is currently locked down.

“I hope he gets out,” the article quoted from two of Mr. Peltier’s immediate family members. “Otherwise, with his health, he’s not going to be alive very many more years,” his sister Betty Ann Peltier Solano told The Forum in June from her Fargo (North Dakota) home. “I was hoping we could spend our last years together. That would be nice,’” the news story reported.

“Peltier Solano, 77, and her sister, Sheila Peltier, 59, have spent the last 47 years with the shadow of their brother’s incarceration hanging over them. “It’s been really painful. Really, really painful,” Peltier Solano said in June.

The federal government said Mr. Peltier will be eligible for another parole hearing in 2039 when he is 94.

But the impact of Mr. Peltier’s denial of parole, and the government’s refusal to grant a compassionate release for an ailing man in prison, a symbol of a suffering people, runs much deeper than just his immediate family. Indigenous rights activists see him as a living martyr and an icon of a people buried alive.

Adam Thunderface, 52, is a member of the Dakota Sisseton Tizaptanna Band and a cousin of Leonard Peltier. He told The Final Call in a telephone interview before the July 2 parole board decision, that Mr. Peltier, like others of his generation, survived the notorious Indian Boarding Schools

[see The Final Call Vol. 41 No. 34] run by the U.S. government between 1819–1969, designed to dismantle Native American sovereignty by isolating Native children from their parents as a means to eradicate their languages, cultures, and their collective memories to prevent passing down knowledge and to force assimilation into White American society.

“Every Native family has been affected by the governmental policies, and one of them was the boarding schools,” Adam Thunderface explained.

“There were a number of different policies that really broke our family structures apart, so most Natives, there was an interruption with the culture being handed down. There was a point where the ones still holding on to the language, holding on to the cultural knowledge and ceremonies, they were really old,” he explained.

“So, the young ones like Leonard Peltier in the American Indian Movement (AIM) started going back to the elders and the medicine people and learning all they could, and they did it just in time for things to be saved, and for us to have our ceremonies to be able to continue.”

Dawn Lawson, personal assistant to Leonard Peltier outside the walls of the Coleman 1 Federal Penitentiary in Central Florida, shared with The Final Call a letter written by Mr. Peltier dated June 26 where he described the punitive actions the prison has taken to silence his voice and ability to influence the culture of his people.

“Living in lockdown, time has twisted into something that has nothing to do with minutes, hours, or years,” Mr. Peltier wrote to his friends, family, loved ones and supporters. “They have taken what little freedom I have outside this box.

Art—gone. Ceremony—gone. Yet they will never take the Spirit of a Sundancer. I have never given them my integrity. I remain undestroyed,” his letter read in part.

“I will not pretend my body is sound,” Mr. Peltier said of his deteriorating health behind bars. “The lockdowns have been tough on all of us, in ways I cannot begin to explain and those on the outside cannot begin to imagine … I am counting on you not to back down. My time is running out here, with no medical care. I do not fear death, returning to Mother Earth’s womb, but I do not want to die in lockdown,” his letter continued.

Describing AIM members as Spirit Warriors, and not as the merciless savages often depicted in racist Hollywood films and television programs that often mocked Native Americans in American popular culture for decades, he said AIM activists demanded justice with dignity in the spirit of the great Native American leader Crazy Horse.

“Do not weep if I am not granted parole. Cry freedom. Coalesce yourselves, galvanize your relationships, establish alliances. In the power of our people, we find strength. Hold your head up high. It is not over, until it is over,” Mr. Peltier said to his people who prayed, hoped and demonstrated for his compassionate release.

Chicago-based Student Minister Abel Muhammad, The Nation of Islam’s representative to the Latin American community and an Indigenous rights advocate under the leadership of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, told The Final Call that the parole board’s decision to deny an aged and infirmed Leonard Peltier a compassionate release from nearly five decades of imprisonment has been consistent with the overall treatment of Indigenous people throughout the Western Hemisphere.

Stating that colonizers and oppressors have often employed the scourging of the strongest as a method to incite fear among the masses, by continuing to make an example out of Leonard Peltier, an elderly man in poor health locked behind prison bars, it conveys the message for the Indigenous people under American rule to know their place and to stay in it.

“Whenever they dealt with the original inhabitants of an area, they used the same mechanisms and systems to divide those communities and then conquer them,” Student Minister Muhammad explained.

“This was a very masterful tactic that was upheld by the educational, as well as the religious indoctrination, that was placed upon the original inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere, so much of what we see today is the byproduct of that which the Europeans produced in terms of depriving the original people of a true knowledge of themselves.”