ATLANTA—Yvette Essounga, a faculty member at Tuskegee University, attended the United Negro College Fund’s UNITE 2022 Summit to learn how to better communicate with and understand her students. She noted that the Black community is plagued with mental health issues and believes it is the duty of faculty to help students cope.

“I’m Black. I’m a woman. I’m an immigrant. I have an accent. And I can relate to many of the struggles that my students go through,” she expressed to The Final Call.

She noted that students love to talk, but they often go silent when something is going on. That’s when she starts calling and checking up on them.

“I’m not a licensed psychologist or anything like that. I’ve seen our students be more withdrawn, less focused, less able to complete their work in a timely manner. Sometimes not even able to attend classes,” she said.

She sat in on a summit workshop titled “Mental Health—From Your Lips to God’s Ears. Approaches to Supporting Student Mental Health.”

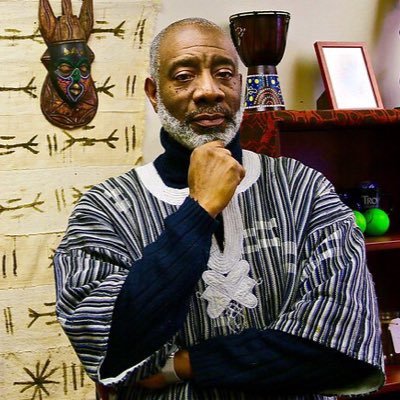

Workshop presenters Dr. Kevin Washington, head of the Department of Psychology/Sociology at Grambling State University in Louisiana, and Dr. Afiya Mbilishaka, a licensed clinical psychologist, explored alternate approaches to student healing.

In 2019, suicide was the second leading cause of death for Black people ages 15-24, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. A report by Mental Health America states that more than 16 percent of Black people, over seven million, reported having a mental illness in the past year. The report linked poverty, homelessness, incarceration, substance use and racism to higher risks of poor mental health.

Dr. Mbilishaka brought up further statistics, stating that one out of four Black people that have mental health concerns get treatment, and of those who do, 50 percent terminate therapy after the first appointment.

She questioned the audience on why Black people may not go back. Answers included unrealistic expectations of what therapy is, the discomfort of being vulnerable, lack of trust, the stigma surrounding mental health, the cost and having a non-Black therapist or one who doesn’t come from the same socioeconomic, cultural or regional perspectives.

Black psychologists made up only four percent of the U.S. psychology workforce in 2018, according to the American Psychological Association’s latest data.

Dr. Mbilishaka designed an approach to therapy that might better appeal to Black people, a community health model called PsychoHairapy. She created it “to secure space for Black people to address mental health and well-being through hair care.”

She stated the theory and practice of the model includes training hair care professionals in micro-counseling techniques, mental health professionals housing private psychotherapy sessions within the hair care setting, facilitating salon and barbershop based group therapy and the distribution of psychoeducational materials and workshops to Black people.

She then presented on a mental health ‘C.A.R.E.’ plan for Black college students: culture, going “back to our roots” and looking at the transformation of Black hair from the continent of Africa through slavey to the present-day United States; affirmation, encouraging Black students and validating their issues; ritual, preparing the mind, body and spirit; and event planning, utilizing cultural aesthetics and popular Black culture, offering business incentives and recruiting and paying Black experts.

Her personal philosophy is do not put anything on your skin or hair that you cannot eat.

“So even thinking about how a lot of our hair products can disrupt our endocrine system, which includes our hormones, which then impacts our mood,” she said, noting how hair products can impact the level of anxiety and depression.

She also recognized the practices of African societies related to hair. In one ceremony, the hair of the baby and mother is shaved to represent safe journeys from the spiritual realm to the physical. The Maasai people of East Africa have a warrior ritual where the sons dye their hair bright red. Once they have completed their time as a warrior, their mothers shave their hair, and they participate in a ceremony where they are bathed in milk.

Imagine if we did this for those returning from incarceration, Dr. Mbilishaka expressed. “Bathe them, welcome them, drum for them, cut their hair. I imagine there would be much lower rates of PTSD.”

Dr. Washington followed behind her by presenting on ‘Afrikan-centered’ approaches and practices.

“We have come to assume that education is something that came out of Europe. In reality, one of the oldest institutions known to man is in ancient Kemet,” he said. “In this particular institution, students will go to learn how to become more like God. Think about that for a moment, that they’re going to school to understand their divinity.”

He tied that concept to the present-day by describing HBCUs as sacred ground.

“If I come from the Creator, if it is written that I’m in the image and likeness of the Creator, then wouldn’t I have the same essence as the Creator?” he questioned.

He explained the importance of transforming the thought of students and teaching them every single day that they are divine.

Programs designed for HBCUs include: Men of Vision Exemplifying Righteous Service (MOVERS), which supports the recruitment, retention and graduation of Black male college students; Success Training Rendering Integrative Development and Enhancement (STRIDE), which supports student athletes academically, socially and personally and facilitates NCAA compliance requirements; and Sistas of STEAM, which provides socio-emotional and academic support for Black female college students in all walks of life.

Dr. Washington also presented HBCU campus community events, “Fitness Fridays,” “Wellness Wednesdays” and “Manhood Mondays.”

Fridays would have a communal Afrikan drum and dance, a healing circle and discussions and support for social and academic life on campus. Wednesdays include a Black mental health student-led radio talk segment and mental health announcements presented by sociology/psychology department faculty.

Participants discussed topics such as suicide, social media pressure, the Black mental health stigma and the connection between terrorism and HBCU campuses. On Mondays, Black men in the campus barbershop discuss mental health topics. In the past, they talked about Black manhood, relationships, police brutality, suicide, race/racism/terrorism, and adjusting to college/emerging adulthood.

“In this process of coming together, we build community,” Dr. Washington said.

He expressed Black students must be informed that they are heirs and custodians to greatness, and expectations of students must be elevated.

He presented a list of HBCU affirmations for faculty: “I am the Greatness of an HBCU. I walk boldly in this space knowing that this is a privilege to be here and not a mere process of living;” “I enliven within my students their innate genius that is waiting to be released and make an impact in the world. We are all Greatness in Motion;” “I am setting an example of excellence in every thought, word and action;” “I am the vision of the Great Ones made manifest in this moment called Now;” “I am the Greatness that is the Essence of this HBCU.”

UNCF’s mental health initiative

The United Negro College Fund surveyed 5,000 HBCU students in June 2020. Thirty-seven percent of students surveyed reported their mental health status declined. In the results of those who said their mental health status improved, one response said it improved because remote learning allowed them to keep the two jobs they need.

Victoria Smith, a strategy analyst with UNCF’s Institute for Capacity Building, and Dr. Jan Collins-Eaglin with the Steve Fund, a nonprofit organization focused on the mental health and emotional well-being of college and university students of color, presented key findings of a pilot mental health survey.

They surveyed 342 students and 419 faculty and staff representing 47 HBCUs. They found that the top student challenges are stress, anxiety and depression. Sixty-five percent of students in crisis are most likely to speak to friends or family members; 72 percent of students are aware of their options for mental health counseling, but only 52 percent feel comfortable visiting the counseling center when needed; 70 percent want to be informed of resources for emotional well-being.

Twenty-five percent of faculty and staff said no training is available about student mental health and wellness, and 49 percent said barriers prevent students from receiving adequate mental health care.

Ms. Smith and Dr. Collins-Eaglin issued a call to action to all HBCUs and predominantly Black colleges to help with a comprehensive, customizable study on Black college student mental health and to form a community of action in a two-year program.

“Part of that is to develop training and develop programs that are culturally relevant, culturally appropriate,” Dr. Collins-Eaglin said.

They are looking for 40 institutions to work with them and are planning a mental health informational webinar on July 19.

Healthcare access and equity

Another topic during the UNCF summit held in mid-June was “Achieving Healthcare Access and Equity in Rural Communities.” Tiffany L. Grayson, program specialist and office manager of Voorhees University’s Liberal Arts Innovation Center in Denmark, S.C., explored methods to increase healthcare access and equity.

According to population data presented by Ms. Grayson, Denmark is a majority Black city of 3,186 residents. It has a poverty rate of about 19 percent, compared to 14.7 percent statewide, and 23 percent of its residents are without any health care coverage.

As of fall 2020, out of 381 students at Voorhees University, 15 percent were insured and 85 percent were uninsured. Only 1.6 percent of students were utilizing telehealth services.

At the university, Ms. Grayson has helped to implement medical telehealth direct access, a live speaker series, on-demand presentations on health and wellness topics and online certification programs.

The process of accessing healthcare started with coalition building and finding agencies that could offer required services at little to no cost. Those agencies include a telehealth partner that provides technical support to campus technologies and offers remote health care services such as clinical care, and a federally qualified health center, which provides comprehensive health care for the medically underserved.

Ms. Grayson and her team implemented a health cooking series. The first live speaker was Chef Kiersten “Kat” Tolbert, an advocate for holistic healing which includes foods and other traditional medical treatments. Chef Tolbert has an “Eat More, Eat Better” initiative, where she teaches 10 segments on topics such as reducing salt in food while preserving taste, utilizing non-traditional seasonings and ways ingredients are beneficial to health.

“Access to healthy foods is access to healthcare,” Ms. Grayson said.

The college also implemented training for community health workers. Community health workers are advocates for a healthier community, educators for individuals about the personal habits that lie in opposition to a healthier future and observers of potential health problems in community settings. The first cohort, which comprised of four students, completed their training and practicum requirements in 2021, and a second cohort will be convened during the fall 2022 semester.

The team also plans to expand on mental health services in the fall.

“We want them to be happy, healthy and graduating, which is the ultimate goal,” Ms. Grayson said.