/GIN

WASHINGTON (IPS/GIN) – A little-known entity that mediates disputes between sovereign nations and foreign investors appears to favor corporations in northern countries, according to an IPS review of pending cases.

Other independent analyses have detected a similar bias in the entity, which is closely affiliated with the World Bank.

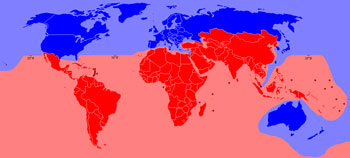

The administrative council of the Washington-based International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) consists of one representative from each of the 155 states that have ratified the center’s founding convention. However, most of the arbiters who actually decide cases come from industrialized countries, even though most of the defendants are from developing nations.

While the decision to submit to the ICSID’s three-member arbitration panels is technically voluntary, many bilateral investment treaties require countries to agree to the center’s jurisdiction.

Of the 300 judges who are looking into 111 pending cases at the ICSID, only 63 came from developing nations. In just one case the three-member tribunal consisted entirely of arbiters from developing nations.

In a case by the U.S. agricultural giant Cargill against Mexico, the arbiters are from the United States, Australia and Canada. In a case against Egypt by the Scandinavian hotel chain Helnan International, the arbiters are from France, Britain and Germany.

Earlier this year, citing suspicions of favoritism, three Latin America nations, Bolivia, Venezuela and Nicaragua, announced their intention to withdraw from the ICSID. Only Bolivia has formally notified the center of its decision, which will take effect this November, according to ICSID officials.

Pablo Solón, Bolivia’s Special Ambassador for Trade and Integration, cited a case brought by Aguas de Illimani, a subsidiary of the French international water giant Suez. Apparently, the International Finance Corporation, an arm of the World Bank Group, was a shareholder in Aguas de Illimani, creating a potential conflict of interest.

The Washington-based center is legally autonomous, but is closely linked to the World Bank, which funds its secretariat. The World Bank president chairs the ICSID’s administrative council. Critics point out that the World Bank itself has long been accused of promoting the interests of the industrialized nations that control its board, such as the United States, Japan and European countries.

The Bretton Woods Project, a bank watchdog group, notes that hearings are often held in Washington, Paris or London, locations that are “convenient for northern investors, but thousands of miles away from where the potentially affected citizen lives.”

The ICSID’s proceedings are mostly held in secret, a practice that ICSID officials say is necessary to protect the privacy of parties. Case details are only announced after a ruling has been made.

Sara Grusky of Water and Food Watch said developing countries have their hands tied by bilateral investment treaties and free trade agreements, which force them to abide by the rulings of the ICSID and other arbitration forums.

ICSID rulings are largely based on some 20 investment laws and more than 900 bilateral investment treaties. About 70 percent of the disputes involve private investment in public services such as water, electricity, and telecommunications, or investments in natural resources such as oil, gas and mining.

In April, the Institute for Policy Studies, a U.S. think tank, and Food and Water Watch, a nongovernmental organization that monitors water investments, jointly published a study that found that 93 percent of the ICSID’s cases were against developing countries.

The 48-page study said 74 percent of concluded and pending cases were filed against “middle-income developing countries” and 19 percent against “low-income developing countries.”

The largest damage award paid in an investor-state case was $877 million, by the Slovak Republic to the Czech bank CSOB, the report found. The largest pending damage claim is $28.3 billion by the British-based Group Menatep against Russia over alleged expropriation of the Russian oil giant Yukos.

The study showed that countries in the former Soviet bloc and in Latin America that rapidly privatized state enterprises and opened their doors to foreign investment have ended up fighting the greatest number of claims.

Cases include disputes between the U.S.-based Occidental Petroleum Corporation, which has filed claims against Ecuador, and the U.S. mining firm Newmont USA, which has filed against the Republic of Uzbekistan. They have also pitted corporate giants such as DaimlerChrysler Services AG, Total, Enron Corporation and BP against Argentina.

Ares International of Italy is seeking settlement against Georgia, and Shell is in a dispute with Nigeria.

The IPS review found that nations such as Chile, Egypt, Panama, Congo, Kenya, Burundi, Venezuela and Indonesia, among many others, are fending off billions of dollars in claims from companies such as Siemens of Germany, the Société Générale de Surveillance of France, Eni of Italy, Mobil and BP America.